Polls showed Juan Carlos Varela trailing in third place going into Sunday’s presidential vote, but the outgoing vice president shocked the country, and he will become Panama’s next president after leapfrogging both the candidate of the outgoing, term-limited president and the candidate of the Panamanian center-left.![]()

With 82.12% of the votes counted, Varela (pictured above), the candidate of the conservative Partido Panameñista (Panameñista Party), one of the country’s oldest parties, led with 39.00% of the vote.

Trailing in second place was José Domingo Arias, the candidate of term-limited, outgoing president Ricardo Martinelli and the center-right Cambio Democrático (CD, Democratic Change), with 31.87%. In a surpassingly weak third place was environmentalist and former decade-long mayor of Panama City Juan Carlos Navarro, the candidate of the center-left Partido Revolucionario Democrático (PRD, Democratic Revolutionary Party), who was winning just 27.79% of the vote.

* * * * *

RELATED: Panamanian presidential race is all about Martinelli

* * * * *

Until the votes were actually counted, the race seemed like it was set become a photo finish between Arias and Navarro.

So what happened?

Martinelli bid to retain influence fails

As it turns out, voters were incredibly wary of Arias, a former foreign trade and housing minister, who was viewed as a figurehead who would enable Martinelli a de facto second term. Martinelli’s wife, Marta Linares, was controversially named as the CD’s vice presidential candidate, a strategy that was arguably unconstitutional — and almost certain designed to maximize Martinelli’s future influence.

Despite a relatively strong record of economic growth and infrastructural progress, Martinelli’s move to enshrine his wife as a potential vice president was widely viewed as a means of perpetuating his influence in Panamanian government, which followed five years of allegations of corruption within the Martinelli administration.

Varela’s convincing seven-point lead over Arias is a fairly strong statement that voters were suspect of Martinelli’s motives. Notwithstanding the single-term limitation on presidential power, Panamanians have not elected a presidential candidate from the incumbent party since the return of democratic elections in 1989. Call it fickle, perhaps, or call it respect for democratic balance, but the Panamanian electorate has once again confounded the notion that a single party will become hegemonic.

A devastating defeat for Navarro and the Panamanian left

But Navarro’s collapse is even more striking. In 2009, the PRD nominated Balbina Herrera, and she lost by a wide margin to Martinelli, who had joined forces with the Panameñista Party, nominating Varela as Martinelli’s running mate. Herrera was largely damaged by her former connection to strongman Manuel Noriega, and her ties to the left wing of the party made her particularly easy to tie to the far-left populist socialism of the late Venezuela president Hugo Chávez.

Navarro, however, was supposed to be the moderate, pragmatic opposite of Herrera, and he campaigned for president this year as a relatively business-friendly neoliberal who would largely carry out many of Martinelli’s economic policies, albeit with greater accountability and transparency.

As the wunderkind mayor of Panama City, he only narrowly lost the presidential nomination of the PRD in 2009 to Herrera. So his certain emergence as the 2014 frontrunner united the PRD in the months and years leading to today’s election. Nevertheless, he will win around 10% less than Herrera, who won 37.65% in the two-way race against Martinelli. Taken together, the right-leaning vote that supported either Arias or Varela totals around 71% — that, correspondingly is about 10% greater than the 60.03% that Martinelli won in 2009, leading a united conservative front that included his own CD as well as the Panameñista Party. The result suggests that the Panamanian left might be in some real trouble. Even more demoralizing for the left, it will be Varela who receives credit for completing the high-profile expansion of the Panama Canal, now expected to be completed in 2016. The last PRD president, Martin Torrijos, who served between 2004 and 2009, initiated the canal’s expansion, which is anticipated to enhance the already robust receipts that the Panamanian treasury enjoys from shipping fees.

What to expect from Varela

Varela’s campaign largely advanced the same agenda as Navarro — he would continue the successful economic, social and infrastructural policies of the Martinelli administration without the corruption and sleaze. In some ways, Varela was always perfectly situated to take credit for the Martinelli administration’s accomplishments while also opposing the worst of its corrupt tendencies. For example, Varela is widely associated with a Martinelli administration plan to give $100 monthly stipends to Panamanians over age 70 who don’t otherwise have access to retirement benefits.

Varela, at age 50, is an engineer by trade, though he comes from one of the country’s richest families, which control’s of Panama’s largest alcohol distillery company.

Varela, who also served as foreign minister between 2009 and 2011, broke with Martinelli three years ago over the issue of corruption and his refusal to support a constitutional amendment allowing Martinelli to run for a second consecutive presidential term, but Varela himself remains under a cloud of suspicion for a money laundering inquiry. Though the most detailed accusations emerged during the most recent election campaign, a newspaper investigation found that he took campaign financing from funds from a global gambling ring that operated from Florida to east Asia. The dodgy bank accounts, whereby money from the gambling ring was transferred to accounts associated with Varela, date to 2009.

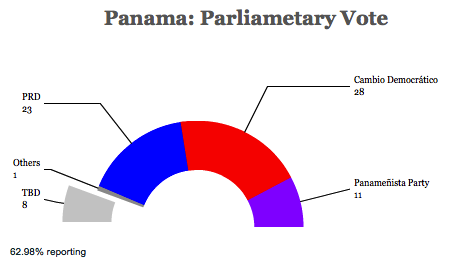

Despite the surprising emergence of Varela as Panama’s next president, his party seems to have finshed in third place in the simultaneous parliamentary elections. Voters also chose all all 71 members of Panama’s unicameral Asamblea Nacional (National Assembly) on Sunday, and the Panameñista Party and its allies are currently expected to win just 11 seats, compared to 28 seats for the CD and its allies and 23 seats for the PRD and its allies, though those numbers are likely to change a little as the final votes are tallied.

That means that Varela will have to nurture the existing parliamentary alliance between the Panameñista Party and the CD in order to govern effectively. Even after Varela distanced himself from Martinelli in 2011, the Panameñista Party continued to provide parliamentary support to Martinelli.

Going into the election, the CD held just 14 seats, but governed in alliance with the Panameñista Party (with 22 seats) and two other minor parties, with the PRD (at 26 seats) in opposition.

If the numbers hold, it will be a curious result — the CD will double its strength in the National Assembly, the PRD will lose a little support, and the Panameñista Party will actually find its legislative caucus halved. It’s an incredibly odd result. That tells me that while Panamanian voters are very happy with the results of Martinelli’s administration, with his policies, and with the CD agenda, in general, and that while voters may have been willing to reelect Martinelli if he had been constitutionally permitted to run for a second term, voters weren’t prepared to back Martinelli’s ‘extraconstitutional’ workaround to retain power for another five years. (I’ll leave it for another day to determine whether that means Panama and other countries in Latin America should revisit the single presidential term limit).

Nonetheless, Varela’s victory gives his party a significantly boost. Had Arias won, it would have called into question the Panameñista Party’s longterm viability. Now the CD will remain under increasing pressure to show that, even as the largest bloc in the Panamanian legislature, it’s more than just a vehicle for Martinelli’s personal political interests.

Though Varela should enjoy strong economic growth, it’s unlikely that he’ll be graced with the kind of 8% to 9% growth that featured during Martinelli’s administration. He’ll also face rising public debt that, thanks to the Canal extension and other infrastructure projects, has now risen to around 40%.

Varela’s party last held office between 1999 and 2004 under Mireya Moscoso, who also governed with a parliamentary minority and who served as president when the United States formal transferred ownership of the Canal to Panama. But the Panameñista Party has a long-standing pedigree in Panamanian politics.

Formed in the 1930s, it’s the party of Arnulfo Arias, who served as president briefly from 1940 to 1941, from 1949 to 1951 and for ten days in October 1968 — in each case, he was overthrown by military coups. At times in its history, including until very recently, it’s also been referred as the Arnulfista Party in honor of its leading 20th century figure.

What’s more, it opposed the military rule of Omar Torrijos in the 1970s and the narcocratic rule of Manuel Noriega in the 1980s, putting it twice on the right side of history, as far as democracy and the rule of law. Conservative by nature, much of its support comes from rural Panama, but Varela won today even in the district that includes Panama City, the country’s urban center where Martinelli introduced a subway (Central America’s first) and where Navarro served capabaly as mayor for ten years, between 1999 and 2009.