The sovereigntist Parti québécois (PQ) has lost power after just 18 months leading a minority government. ![]()

![]()

Instead, former health minister Philippe Couillard, barely a year after winning the leadership of the federalist Parti libéral du Québec (Liberal Party, or PLQ), will lead a majority government as Québec’s new premier.

Incredibly, in the riding of Charlevoix–Côte-de-Beaupré, premier Pauline Marois has lost her race against Liberal Caroline Simard, and in an address to supporters, announced she would step down as PQ leader as well.

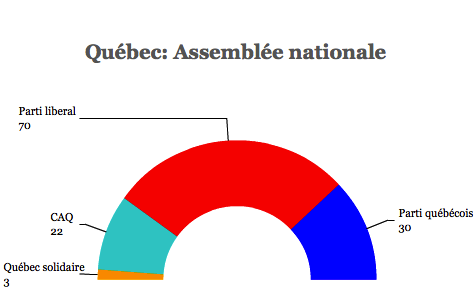

Here’s the breakdown of the 125 ridings in Québec:

When she called a snap election in March, Marois had every reason to believe that she would sail through the election and win a majority government for the PQ.

Conservative Canadian prime minister Stephen Harper was so worried about the prospect of a separatist majority in Québec that he reached out to the leaders of the other major parties, including Liberal Party leader Justin Trudeau and New Democratic Party leader Thomas Mulcair for advice. Though Trudeau and the federal Liberals endorsed Couillard and the PLQ, the Tories and the NDP have remained neutral.

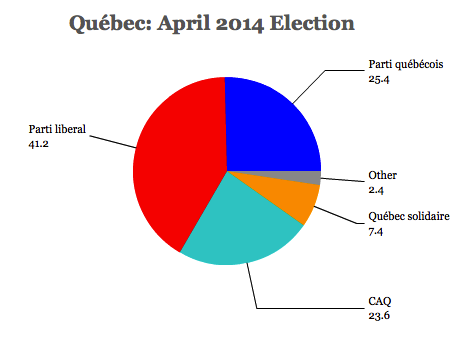

With nearly 97% of the vote reporting, here are the vote totals:

The last time the PQ won such a small share of the vote in a provincial election was in 1970, when it won just 23.06%, when it was running in its first election after its foundation in 1968.

The last time the PQ won such a small share of the vote in a provincial election was in 1970, when it won just 23.06%, when it was running in its first election after its foundation in 1968.

The PQ has suffered what might be an even more humiliating defeat than its 2007 showing, when the PQ placed third, behind both the Liberals and the predecessor to the CAQ, the Action démocratique du Québec (ADQ) — it won just 36 seats and 28.5% of the vote.

Among the key individual races:

- In L’Assomption, François Legault, the leader of the center-right Coalition avenir Québec (CAQ) won his race against the PQ’s Pierre Paquette, a former federal MP from the sovereigntist Bloc québécois.

- Couillard easily won a race in his riding of Roberval, which was supposed to be a difficult race against the PQ’s Denis Trottier, an incumbent since 2007.

- In Saint-Jérome, former Quebecor CEO, Pierre Karl Péladeau defeated Liberal candidate Armand Dubois — though Péladeau played a controversial role in the election campaign, he could well become the PQ’s next leader.

- In Laval-des-Rapides, the 22-year-old former student leader Léo Bureau-Blouin lost his bid for reelection to Liberal businessman Saul Polo.

- In Crémazie, PQ language minister Diance De Courcy and in Saint-François, PQ health minister Réjean Hébert lost.

The CAQ had a much better night than it could have expected. It will improve on its current 19-seat caucus by a handful of seats.

There’s no doubt that the PQ campaign now seems like an incredible miscalculation, and Marois will almost certainly step down as the PQ’s leader. But how did Marois and the PQ fall so far? Here are four reasons that show how tonight’s result came about.

1. Marois never focused on health care, jobs and the economy — in government or in the campaign.

In the August 2012 election, Marois’s PQ had all the momentum on its side — Charest had alienated just about everyone in Québec between the allegations of corruptions over government construction contracts, his attempt to raise student tuition fees, and his heavy-handed police response to student protests.

Notwithstanding, the Liberals only narrowly lost that election, and Québecois voters entrusted a minority government to Marois. The message seemed to be that the electorate was willing to give the PQ a probationary shot at governance.

Early on, however, Marois made it clear that her government’s priorities would be cultural issues, with a high-profile push to amend La charte de la langue française (the Charter of the French Language), popularly known as Bill 101, which establishes the regime of protection for the use of the French language in Québec. Particularly, Marois advanced Bill 14, which would have mandated the use of French in all businesses with 26 or more employees, among other changes.

Though the Marois government eventually gave up on French legislation, it failed to revoke the unpopular $200 health care ‘contribution’ that the Charest government instituted and that the PQ promised to repeal. It took Marois until February 2014 to get around to raising the minimum wage (by 20 cents to $10.35, which doesn’t take effect until May).

Even as Marois moved from Bill 14 to her push to enact La charte de la laïcité (‘secular charter’), which would ban public sector workers from wearing turbans, hijabs or ‘large’ crucifixes, she never quite prioritized job growth, improving health care or economic growth, even though Québec voters have routinely reported in poll surveys that those issues are more important to them than issues like sovereignty, language laws or the secular values charter.

It’s not that Marois’s government hasn’t achieved economic or health policy goals, but they haven’t been its priority.

2. Québec’s voters simply don’t want a referendum on independence right now.

Polls consistently show that between 60% to 70% of Québec’s voters don’t want the government to pursue a referendum on independence. That could change in the future, of course, given the changing demographics of Canada and Québec, or in light of any number of political outcomes in Ottawa.

But today, it’s not a priority — not even among the PQ’s Francophone base outside of Montréal and Québec City.

When Pierre Karl Péladeau, the former CEO of Quebecor, announced his candidacy, the PQ hoped that his business background would build what already seemed like a lack of credibility on economic issues.

Instead, Péladeau veered off course to talk about Québec independence — he seemed like he was running for office not to become a credible finance minister in a future PQ government, but the leader of a third Québec independence campaign.

It didn’t help when Marois spent the following week daydreaming in public about the consequences of a third referendum, holding forth on whether Canada and an independent Québec would share the same currency or porous borders. The diversion only showcased that Marois wasn’t focused on bread-and-butter issues like economic growth, jobs and health care.

3. Couillard turned out to be a better campaigner than expected.

He could have been the Michael Ignatieff of Québec. A cerebral, well-meaning Liberal who’s returned from the private sector to deliver his party from the wilderness — but instead delivers it to even lower depths.

Instead, those qualities seem to have helped Couillard — he came across as a cool, confident leader, and he slowly overtook Marois as the electorate’s preferred choice for premier. In the first leaders’ debate, he effectively presented himself as a capable alternative (in contrast to an angry, aggressive Marois). Couillard was the target in the second debate and, while it wasn’t a perfect performance, he more than held his own.

Couillard was a popular health minister between 2003 and 2008, and it was often claimed that he was more popular than Charest.

Time and time again, Couillard has taken unpopular decisions in Québec — defending the benefits of bilingualism, opposing the secular values charter, opening the door for Québec to ratify the 1982 Canadian constitution. None of those positions are typically vote-winners in Québec. But it’s possible that by openly admitting his views, Couillard won the trust of the electorate — in contrast to Marois’s refusal to say whether she would try to hold a referendum, answering only that she would conduct a referendum when her government decides ‘Québecois are ready for it.’

4. The debate over the ‘secular values’ charter was wedge politics at its worst.

When Marois turned from Bill 14 to the secular charter, it was an obvious attempt to use a cultural wedge issue to divide the electorate — it’s not unlike, say, the Swiss ban on minarets. Though polls show that more Québécois voters support the charter than oppose it, it’s not necessarily the kind of vehicle that can win an election.

Initially, it seemed like a great ploy. The PQ’s strength has always been that it can win votes by defending the traditional values of Québec — us (French-speaking Québecois) versus them. With the secular values charter, Marois thought that she had found a way to utilize an ‘us versus them’ dynamic without wading back into the French language and independence fights.

Couillard found a way to put Marois on the defensive, arguing that Marois would effectively fire public workers solely on the basis of their religion, stripping bare the kind of anti-Muslim animus that’s behind the ‘secular values’ charter, and he pounded Marois for wasting government time on the secular charter instead of unemployment or economic growth.

Photo credit to Ryan Remiorz/The Canadian Press.