Tokyo certainly seems to have a fondness for electing colorful characters as its governors — and its newly elected governor appears like he will be no exception.

Tokyo certainly seems to have a fondness for electing colorful characters as its governors — and its newly elected governor appears like he will be no exception.![]()

![]()

Yōichi Masuzoe (舛添 要), who easily won the Tokyo gubernatorial election on Sunday, first became well-known in the 1990s as a television commentator. In 1998, he wrote a book, When I Put a Diaper on My Mother, which detailed the process of caring for his elderly mother and gave Masuzoe a platform to discuss health and aging in Japan. That’s particularly relevant for Japan, which has the world’s second-highest median age (44.6, just 0.3 years higher than Italy), and where the population peaked at just over 128 million in 2010 in what demographers believe will be a massive depopulation over the coming decades.

Masuzoe (pictured above) first ran for the Japanese governorship in 1999, though he placed third with just 15.3% of the vote. Elected to the House of Councillors, the upper house of the Diet (国会), Japan’s parliament, in 2001, Masuzoe rose through the LDP ranks. He chaired a constitutional panel in 2006 that advocated amending Japan’s Article 9, thereby allowing the Japanese Self-Defese Forces to become a full army. Shinzō Abe (安倍 晋三), who was then in his first stint as Japan’s prime minister, appointed Masuzoe as Japan’s minister for health, labor and welfare, a position he held between 2007 and 2009, when the LDP suffered its most severe postwar electoral defeat.

He left the LDP in 2010 to form the New Renaissance Party (新党改革) at a time when his national profile seemed to be rising. But by the time a national election came along in December 2012, the LDP was set to win a landslide victory under Abe and his economic program, popularly dubbed ‘Abenomics.’ Eclipsed by the Japan Restoration Party (日本維新の会), a merger of the two new parties of Tokyo’s governor at the time, Shintaro Ishihara (石原 慎太郎), and Osaka’s young mayor, Tōru Hashimoto (橋下 徹), the New Renaissance Party failed to win a single seat.

Today, the Japan Restoration Party is setting its sights somewhat lower after a disappointing result in the July 2013 elections to the House of Councillors and a series of bad publicity for Hashimoto, who defended the use of ‘comfort women‘ by Japanese soldiers in World War II in May 2013, has called snap elections in Osaka, where he’ll stand for reelection after proposing the merger of Osaka’s city and prefectural governments.

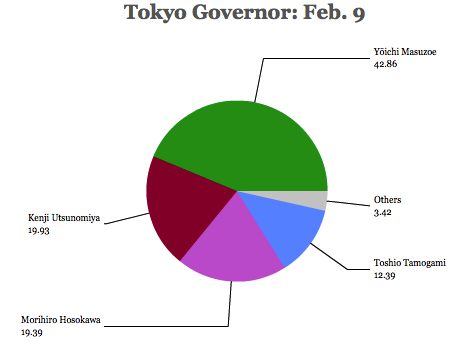

But Masuzoe is today riding high — running as an independent with the support of the LDP and its conservative Buddhist ally, New Kōmeitō (公明党, Shin Kōmeitō), Masuzoe won the election in a near-landslide, garnering more than double the support of his nearest challenger, Kenji Utsunomiya (宇都宮 健児), a Japanese attorney and anti-nuclear activist, and the runner-up in Tokyo’s December 2012 gubernatorial election.

In third place was the man who once threatened to knock Masuzoe from his frontrunner perch — Morihiro Hosokawa (細川 護煕), who served as prime minister between August 1993 and April 1994, leading the first non-LDP government since 1955. Though he resigned over accusations of bribery, and thereupon left politics, the DPJ recruited him for the 2014 Tokyo race.

Though Hosokawa had the formal support of the DPJ and Masuzoe the formal support of the LDP, several top Democratic Party figures backed Masuzoe. Junichiro Koizumi (小泉 純一郎), the LDP architect of economic reform in the 2000s, backed Hosokawa, in large part due to his anti-nuclear stance.

In contrast to Utsunomiya and Hosokawa, who pledged to limit spending on the 2020 Olympics and opposed a return to nuclear energy, Masuzoe supported return to nuclear energy and now stands a good chance of ushering Tokyo through to the 2020 Olympics with plenty of LDP patronage, though Masuzoe will face reelection in 2018. Earlier Monday, Abe’s government appeared to push with renewed vigor to restore Japan’s nuclear power capability just three years after the Fukushima nuclear meltdown, and at times, the Tokyo gubernatorial race felt like a showdown between Abe and Koizumi, arguably the two most successful political figures in Japanese history of the past two decades.

The truth is that Tokyo voters weren’t thinking about the contest as a referendum on nuclear power, but competent city governance. Abe, still basking in the success of his economic program (though that success may be somewhat less impressive than it was half a year ago), was always going to cast a large penumbra in the race.

Moreover, Utsunomiya and Hosokawa split the mostly anti-Masuzoe vote — had they united, they would have stood a strong chance at overtaking him, thereby denting the political invincibility that Abe and the LDP have enjoyed since December 2012. The fourth-place candidate, Toshio Tamogami, a former general in the Self-Defense Forces, waged a largely nationalist, militaristic campaign, enough to win 12.4% of the vote that might have otherwise gone to Masuzoe.

Masuzoe expressed other odd views during the campaign — he indicated, rather bizarrely, that he didn’t believe women were capable of leading the country, inspiring an equally ‘sex boycott‘ among Tokyo women.

Back in Tokyo, Masuzoe is in good company historically though, given that the Tokyo governorship has attracted some of Japan’s most colorful politicians on the left and the right.

Ryokichi Minobe (美濃部 亮吉) was a socialist who stole the Tokyo governorship from the dominant Liberal Democratic Party of Japan (LDP, or 自由民主党, Jiyū-Minshutō) at the height of its postwar power in 1967 on a Socialist/Communist coalition — and this was just three years after the LDP staged the 1964 Summer Olympics in Tokyo. He served until 1979, when the LDP returned to power for the next 16 years.

Yukio Aoshima (青島 幸男), previously an actor, author, director and screenwriter, won the Tokyo governorship in 1995 on an essentially independent ticket.

Ishihara, an author and a filmmaker who found a later political career with the LDP, won the governorship between 1999 and 2012, when he jumped back to the national political scene. Ishihara is one of the most consistently conservative members of Japan’s political stage, with sharp nationalist views against the People’s Republic of China and North Korea, and his push to buy to Senkaku Islands (called the Diaoyu Islands by China) caused an international territorial row between Japan and China. But he governed Tokyo itself with a broad policy brush, cutting spending here, raising taxes on banking profits there, instituting a cap-and-trade emissions tax, and winning the 2020 Summer Olympics for Tokyo, making it one of five cities to host the Summer Games more than once.

His immediate successor, Naoki Inose (猪瀬 直樹), Ishihara’s vice governor since June 2007, won election in his own right in December 2012 with the LDP’s support, but he resigned in December 2013 after his involvement in a fundraising scandal, leading to Sunday’s gubernatorial election.

Tokyo’s governor is one of the most important figures in Japan, exercising control over Tokyo’s massive budget and wielding a strong role vis-à-vis the metropolitan assembly, a 127-member body, which the LDP currently controls with 59 seats. With 13.2 million people, Tokyo is the most populous of Japan’s 47 prefectures, and it represents over 10% of Japan’s 127.6 million population.