In the two countries where the Arab Spring ‘revolutions’ of early 2011 quickly toppled long-standing dictators, Tunisia has become the ‘success story’ and Egypt its ‘failure.’ Whereas Egypt is grinding through what’s now three years of fits and starts in its political development, Tunisia today seems like it’s on a stronger and more productive path to economic stability and political harmony.![]()

![]()

First off, it’s hard to know exactly what anyone means by ‘success’ with respect to Islamic democracy, especially in the context of North African history, which has little history of democratic institutions. By the way, is the Lebanese political system a ‘success’? Is Indonesia’s? Turkey’s? Iran’s? Pakistan’s?

Moreover, the truth isn’t so easily distilled down to the mantra of ‘Tunisia good, Egypt bad,’ and it wasn’t always so clear that Tunisia would succeed where Egypt today seems to have failed. Experiments in political change in both countries continue to develop, and there’s still time for Egypt to ‘succeed’ — and for Tunisia to ‘fail.’

Tunisia, this week, marked the third anniversary since the fall of its former president, Zine El Abidine Ben Ali.

Egypt and Tunisia both enacted new constitutions in January, inviting a comparison between the two approaches to post-revolutionary politics.

In Egypt, the military-led government pushed through a more secular version of last year’s constitution with stronger protections for human rights, though it did so by controlling the Egyptian media, deploying violence to silence its critics and excluding the Muslim Brotherhood (جماعة الاخوان المسلمين) from joining the political debate. Not surprisingly, the Brotherhood boycotted the constitutional referendum, and the new constitution passed with over 98% of the vote. Last month’s vote was the third constitutional referendum in Egypt since Hosni Mubarak’s fall from office in February 2011. Egyptians also overwhelmingly endorsed constitutional reforms in March 2011 and in December 2012, the latter a hasty effort by former president Mohammed Morsi that hijacked the process from Egypt’s preexisting constituent assembly to enshrine the Brotherhood’s vision for Egypt into a new constitution.

Tunisia took a different path to constitutional reform, playing the tortoise to Egypt’s hare. It didn’t jump to an immediate referendum — and it won’t hold a popular referendum on Tunisia’s new constitution. Instead, its interim government conduction an election in October 2011 to choose a 217-member constituent assembly that late last month promulgated a constitution that’s even more progressive than Egypt’s, in line with the historically secular tradition of Tunisian governance and the moderate nature of Tunisian Islam — it protects freedom of expression and religion and provides for some of the strongest women’s rights in the Arab world.

Mehdi Jomaa (pictured above), an independent who most recently served as minister of industry, took office on January 29 to lead a caretaker, technocratic government designed to keep Tunisia on track through the planned elections later this year.

The charter won the support of secular members of the constituent assembly, but also the support of the assembly’s largest bloc, the Islamic democratic Ennahda Movement (حركة النهضة, Arabic for ‘Renaissance’). While the constitution doesn’t enshrine sharia law or even proclaim Tunisia to be an ‘Islamic state,’ it incorporates Islam as Tunisia’s state religion and states in its preamble the ‘attachment of our people to the teachings of Islam.’ That has left the constitution open to charges that it’s vague and inconsistent, especially Article 6, which attempts to provide for freedom of religion and protect against ‘offenses to the sacred’:

The State is the guardian of religion. It guarantees liberty of conscience and of belief, the free exercise of religious worship and the neutrality of the mosques and of the places of worship from all partisan instrumentalization.

The State commits itself to the dissemination of the values of moderation and tolerance and to the protection of the sacred and the prohibition of any offense thereto. It commits itself, equally, to the prohibition of, and the fight against, appeals to Takfir [charges of apostasy] and incitement to violence and hatred.

Despite the shortcomings of Tunisia’s constitution, it wasn’t always a foregone conclusion that the Ennahda Movement and Tunisian secularists would reach a compromise — Ennahda always had enough strength to kill the constitutional process if it truly wanted. By 2013, rising political violence from within the Salafist, conservative ranks of Tunisian Islamists threatened the entire venture, notably the assassinations by radical Islamists of Chokri Belaïd, the leader of the leftist, secular Democratic Patriots’ Movement, in February 2013, and of Mohamed Brahmi, the founder and leader of the socialist/Arab nationalist People’s Movement, in July 2013.

Egypt, in contrast, has now held three constitutional referenda, November 2011/January 2012 parliamentary elections that were annulled by Egypt’s top court and a May/June 2012 presidential vote that ended in Morsi’s election, his ultimate overthrow by the Egyptian army in July 2013, and a brutal crackdown against Morsi’s supporters. Egypt is expected to hold a presidential election this spring, with another parliamentary election to follow, and army chief and defense minister Abdel-Fattah El-Sisi is almost certain to run and likely to win, representing, in essence, the re-Mubarakization of Egypt.

Whereas Egypt’s 2014 elections will be its third restart at attempted representative government since Mubarak’s fall, Tunisia’s unscheduled 2014 elections follow three years of careful, if difficult, work by the constituent assembly and Tunisia’s interim government.

So what marks the key differences that explain why Tunisia and Egypt are so far apart today?

2011: Egypt turned back to military rule while Tunisia built civil society

After Ben Ali fled the county in January 2011, a unity government formed from among all elements of Tunisian society, including three major opposition parties, the Tunisian General Labour Union (UGTT, الاتحاد العام التونسي للشغل) and even members of Ben Ali’s ruling Constitutional Democratic Rally (RCD, التجمع الدستوري الديمقراطي), the party of Tunisia’s first president, Habib Bourguiba, who led the country to independence from France in 1957. Though Bourguiba ruled for 30 years as an essentially authoritarian dictator of a one-party state, he enshrined the concept of separation of state and religion into Tunisia’s first constitution, and he prioritized public education, women’s rights, health care and other public services and infrastructure.

The provisional government, initially headed by Mohamed Ghannouchi, who had previously served as Ben Ali’s technocratic prime minister since 1999, was controversial for the inclusion of former RCD officials. Further protests, which resulted in fatal clashes between protesters and Tunisian forces, forced Ghannouchi to step down in February 2011 as acting president and prime minister. Béji Caïd Essebsi, who served in the early 1980s as Bourguiba’s foreign minister, replaced Ghannouchi as prime minister, and his government made gradual process — it pursued criminal charges against Ben Ali and scheduled the October 2011 elections for a constituent assembly. Meanwhile, Tunisian courts in March 2011 ruled that the RCD would be disbanded and banned from future political participation, which de-escalated tensions in the immediate aftermath of the Tunisian revolution.

The key difference between the initial transitions in Tunisia and Egypt is the role of the military. Tunisia’s interim government, however imperfect, was a broad-based group of various civilian interest groups. Egypt immediately came under the control of the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces, which delayed the first parliamentary vote for nearly a year and the first presidential vote for nearly a year and a half.

2012-13: Ennahda approached politics with more pragmatism than the Brotherhood

Tunisia’s October 2011 constituency elections paved the way for the emergence of the Ennahda Movement, an Islamic democratic party with free-market liberal leanings. Though the Ennahda Movement has its roots in the same teachings as Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood, it increasingly assumed a more moderate, pro-democratic edge in the 1980s under the influence of its leader Rachid al-Ghannouchi. Upon the fall of the Ben Ali regime, Ghannouchi returned to Tunisia from over two decades in exile in London and the Ennahda Movement quickly became the strongest political vehicle in the country. It won 89 seats and 37.0% of the vote in an election that saw a turnout of just under 52% of the electorate.

That mirrors the success of the Muslim Brotherhood,* which won 37.5% of the vote in the parliamentary elections held there between November 2011 and January 2012, and whose presidential candidate Morsi narrowly won the June 2012 runoff against former Mubarak regime official and air force commander Ahmed Shafiq.

In Tunisia, Ennahda teamed up from the outset with the second-place winner, the Congress for the Republic (CPR, المؤتمر من أجل الجمهورية), a center-left secular party founded in 2001, and the third-place winner, the Democratic Forum for Labour and Liberties (Ettakatol, التكتل الديمقراطي من أجل العمل والحريات), a social democratic secular party founded in 1994. The three groups together commanded a majority in the constituent assembly, and they agreed to form an interim government of national unity — Hamadi Jebali, the long-time secretary-general of Ennahda, would became prime minister, CPR leader Moncef Marzouki, who had returned from exile in France after Ben Ali’s fall, became president, and Ettakatol leader Mustapha Ben Jafar became president of the constituent assembly.

By contrast, once Morsi took power in Egypt, he increasingly isolated anyone who lacked ties to the Muslim Brotherhood. He left unfulfilled a promise to appoint to the Egyptian vice presidency a woman and a Christian. In November 2012, he tried to assume dictatorial powers to push through a new constitution, rather than work through the constituent assembly to develop a constitution through consensus. By the end of his year in office, he had even eschewed a promise to elect Egyptian governors, instead installing Brotherhood allies to lead Egypt’s 27 governorates.

The Ennahda-led government in Tunisia, meanwhile, wasn’t always perfect. It clashed with its secular allies and it clashed with its Islamist allies, enacting a curfew following Salafist riots against the sale of alcohol and against an art exhibition in spring and summer 2012. But the Jebali government won a conviction against Ben Ali for theft in absentia, and it sentenced him to 35 years in prison, even as he remained exiled in Saudi Arabia.

The most critical moment for Ennahda came after the Belaïd assassination, when Jebali called for a new, technocratic government and Ennahda, his party, resisted Jebali’s urge to let go of power. Ultimately, Jebali resigned as prime minister, and Ennahda got its way. Instead of a unity government, Ennahda instead pushed through Jebali’s interior minister, Ali Laarayedh, a longtime Ennahda leader, as prime minister, winning the confidence of the constituent assembly with a slimmed-down cabinet of independent officials. It arguably distracted the constituent assembly from progress for much of the 2013.

Even after Ennahda derailed Jebali’s plan for a technocratic government, and despite the link between Islamists (perhaps with ties to Ennahda) and the Belaïd and Brahmi assassinations, negotiations continued on the Tunisian constitution and, with the final passage of the new constitution and the appointment of the Jomaa government last week, 2013’s troubles seem like a temporary road bump on the path to greater political participation, not a permanent detour.

In the same way, Egypt — even now — could get back on track if El-Sisi and his allies in the Egyptian military back away from a presidential bid that would represent a return to the bad old days. Even if El-Sisi commands the majority support of the Egyptian electorate, it will be a triumph of the military’s dominance as much as the expression of popular will, especially with the Brotherhood subdued and Egypt’s Salafist Al-Nour Party (حزب النور, Arabic for ‘Party of the Light’) cowed into submission.

2014: It’s the economy stupid

So what comes next for Tunisia?

The new government must pass an electoral law and the country must navigate upcoming elections with the same dexterity and moderation that marked much of the transition period.

Having set a deadline to hold presidential and parliamentary elections by the end of 2014, Tunisia’s political landscape has changed in the ensuing three years of interim government. Essebsi, the transitional prime minister from 2011 and Taïeb Baccouche, a former secretary-general of the UGTT, former president of the Arab Institute of Human Rights and Essebsi’s former education minister founded Nidaa Tounes (حركة نداء تونس, Call for Tunisia), a coalition of secular parties and forces that now threatens Ennahda, which has lost popularity over the course of the past three years. The two parties are likely to compete fiercely for control of Tunisia’s presidency and parliament. The secular, leftist and Arab nationalist Popular Front (الجبهة الشعبية), another broad coalition of parties, including those led by Belaïd and Brahmi until their deaths in 2013, is expected to emerge as a force in the legislative elections as well.

The next priority of Jomaa’s government — and the first priority of any elected government — should be Tunisia’s economy.

After contracting by 2.0 percent in 2011, Tunisia’s economy grew by 3.6% in 2012 and an estimated 2.6% in 2013. But that’s far below its potential, given its preferred status with the European Union, through an association agreement signed in 1996 and that took full effect only in 2008. Eliminating corruption and greater liberalization could also boost its export- and tourism-based economy. Tunisia is ranked 77th in Transparency International’s 2013 Corruption Perceptions Index — much better than neighboring Algeria (94) oil-rich Libya (172), Egypt (114) and even better than Greece (80) and not incredibly far behind more established economies like Italy (69).

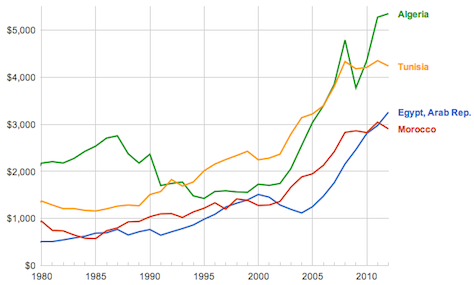

Tunisia’s GDP per capita has since the 1960s been higher than Egypt’s — and so it is today.

Ben Ali, to his credit, boosted foreign investment and attracted tourists from Europe. While Mubarak presided over a stultified, state-heavy economy, Ben Ali in the 1990s and 2000s increasingly liberalized and diversified the Tunisian economy. Although unemployment remains high in both Egypt and Tunisia, and the Tunisian unemployment rate ticked up from 13% in 2011 to 16.5% in July 2013, Tunisia has grown at a faster clip than in Egypt, where political turmoil has overwhelmed a more pressing need for economic reform. That doesn’t mean the Tunisian economy shouldn’t be a priority. It’s not in incredibly better shape than it was in three years ago, and it was the frustration and harassment of an unemployed fruit peddler, Mohamed Bouazizi, that caused Bouazizi to light himself on fire in Tunis in December 2010 that first set into motion the protests that ultimately ousted Ben Ali — and fanned the flames of Egypt’s much larger revolution just weeks later.

Top photo credit to Fethi Belaid/AFP.

* Technically, the Muslim Brotherhood, a group with social and religious interests far wider than politics, competed in elections through its exclusively political arm, the Freedom and Justice Party (حزب الحرية والعدالة).