A crisis over whether to approve the sale of part of Denmark’s state energy company to Goldman Sachs divides the country’s beleaguered minority government, leaving the first female Danish prime minister and her administration in jeopardy. ![]()

It sounds like an episode of Borgen, the acclaimed television show about Danish political intrigue and the human costs of public office.*

But it was real-life Danish politics last week, when Helle Thorning-Schmidt pushed through a controversial sale of stock amounting to 18% of DONG (Danish Oil and Natural Gas) Energy, the national energy company, to Goldman Sachs, even though nearly seven out of 10 Danish voters oppose the sale and worry that Goldman will hold too much power over management and other key decisions.

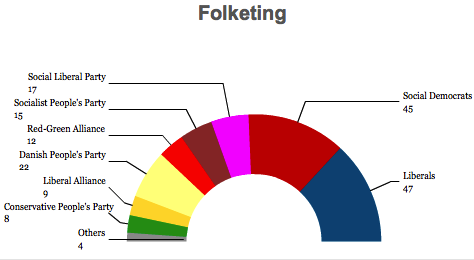

Thorning-Schmidt (pictured above) leads the Socialdemokraterne (Social Democrats), the largest center-left party in Denmark. In the September 2011 parliamentary elections, the Social Democrats actually lost a seat. The largest party today in the Danish parliament is Venstre (Liberals, literally the ‘Left’), Denmark’s primary center-right party.

But the strength of other leftist parties in the 179-member Folketing, the Danish parliament, allowed Thorning-Schmidt to pull together a minority government with the coalition support of two additional parties. The first is Det Radikale Venstre (Danish Social Liberal Party, literally the ‘Radical Left’), a centrist liberal party that gained eight seats in the 2011 election. Its leader, Margrethe Vestager, currently serves as deputy prime minister and minister for economic and interior affairs.

The second is the Socialistisk Folkeparti (the Socialist People’s Party), a democratic socialist party that lost seven seats in 2011. Accustomed to opposition, the party joined government only for the first time since 1959, and its leader Villy Søvndal became foreign minister. But Søvndal stepped down in September 2012, due to criticism within the party about the 2011 losses and sniping that he was focusing more on government than on the party leadership. and in the ensuing leadership contest in October 2012, Annette Vilhelmsen defeated Astrid Krag. Though many party leaders supported Krag, Vilhelmsen’s victory represented a triumph for the party’s left wing, though the party never fully united behind Vilhelmsen’s leadership. Vilhelmsen clashed often with her coalition partners over economic policy, and it was Vilhelmsen’s decision to pull the party out of Thorning-Schmidt’s coalition at the end of last week, declaring that it wouldn’t be a part of government ‘at all costs.’

The decision split the Socialist People’s Party, former leadership aspirant Krag last week left the party to join Thorning-Schmidt’s Social Democrats, and Vilhelmsen herself stepped down as leader, leaving the party’s future direction somewhat in disarray.

In immediate terms, it leaves the Thorning-Schmidt government with just 62 seats, 28 short of a majority in the Folketing. Though Vilhelmsen left the formal coalition, she said that the Socialist People’s Party would continue to support the government from outside the coalition. That’s the same posture as the Enhedslisten – De Rød-Grønne (Red-Green Alliance), the most socialist of Denmark’s four major leftist parties. Together, with their backing and the support of three legislators from the Faroe Islands and Greenland, it’s just enough to keep Thorning-Schmidt afloat.

Thorning-Schmidt yesterday reshuffled her cabinet in light of her smaller coalition. Holger K. Nielsen, who succeeded Søvndal as foreign minister only in December 2013, will now be replaced by Martin Lidegaard, a member of the Social Liberal Party and the previous climate and energy minister.

Thorning-Schmidt enacted tax reform in 2012, with the support of the Liberals and against the wishes of many legislators in her own coalition. The reforms raised the top tax rate as a formal matter, but effectively cut taxes for many of Denmark’s high-income earners in a bid to boost incentives for a shrinking Danish workforce and in light of the realization that the Danish budget can’t support the current level of social welfare benefits. Though the tax reform won’t go into effect until 2016, it comes at a time when Denmark faces sluggish economic prospects, even if far removed from the economic depression of southern Europe. Denmark likely returned to very modest GDP growth in 2013 after a 0.5% contraction in 2013.

Taken together, the four leftist parties won just 50.2% of the vote in the previous election, with the Liberals and four other conservative parties taking 49.8% of the vote. Almost immediately after the election, however, polls showed voters migrating to the Liberals. The next election must take place only before September 2015, and despite the latest tumult within Thorning-Schmidt’s government, it’s not expected that Denmark will go to the polls anytime soon.

A February 2 Voxmeter poll shows that the Liberals would win 28.7% in an election, to just 19.9% for the Social Democrats. The Dansk Folkeparti (Danish People’s Party), a nationalist conservative party, would see its support rise significantly to 17.1%. The Socialist People’s Party would win just 3.1%, a massive drop from the 9.2% it won in 2011, as its base moves toward the Red-Green Alliance, which would win 11.6%. The five conservative parties would win 56.1% of the vote to just 43.5% for the four leftist parties.

Though the Liberal leader, Lars Løkke Rasmussen, who served as prime minister from 2009 to 2011, worked with Thorning-Schmidt on issues like tax reform and the most recent BONG Energy sale, he seems very likely to return to the premiership after the next elections.

Prior to the deal, the Danish government owned 76% of DONG Energy, founded in 1972 to exploit the newly discovered North Sea gas and oil deposits and, in recent years, has acquired Danish electricity generators and expanded into wind power, making it by far Denmark’s largest energy company. Denmark’s oil and gas, combined with coal production and a wind energy industry that generates between 20% to 30% of the country’s electricity, gives the country a dynamic energy sector and makes Denmark self-sufficient in meeting its energy needs.

* Having watched all three seasons of Borgen, I agree that it’s among the best political television dramas I have ever watched — and that’s from someone who never quite saw the fuss over The West Wing.