RAMALLAH — Among the highlights of my week in Israel and the West Bank were a couple of days spent in Ramallah, the de facto capital of the West Bank, if not the entire area controlled by the Palestinian Authority.![]()

Instead of pushing through a crowd of tourists and a throng of horrible souvenir shops in Bethlehem or touring a 1960s-era church in Nazareth, you’d be better served to spend a day and night walking through this most incredible of cities, which now has the vibrant feel that I once imagined East Jerusalem must have had prior to the Six Days War in 1967, during which Israel took military control of east Jerusalem and all of the West Bank (plus the Golan Heights and Egypt’s Sinai peninsula), and prior to the construction in the last decade of a security wall that’s made it relatively more difficult to get from the Israeli side of the wall to the Palestinian side.

While I wouldn’t say that East Jerusalem is moribund, it’s clear that it lacks the kind of energy that’s obvious from five minutes on the streets of Ramallah, which resembles something like a miniature Hamra Street in Beirut (without the Syrian Social Nationalist Party thugs hanging around). The heart of modern Ramallah, al-Manara Square, is actually a five-pronged circle flanked by everything from falafel stands to the ‘Stars and Bucks Café,’ and it’s capped by a monument featuring four stone lions (pictured above).

Ramallah, which translates to ‘God’s mountain’ in Arabic, is a relatively new city, founded in the 16th century and populated as a predominantly Christian city for much of its history. Even today, Ramallah has only around 40,000 inhabitants, but when taken together with al-Bireh, once a separate city, the entire metropolitan area is home to around 65,000 Palestinians.But if you scratch beneath the surface, there are a lot of theoretical and tangible problems with the Ramallah boom — and Naomi Zeveloff explained them almost as brilliantly as possible in a piece last year for Guernica:

Some Palestinians see the boom as a perversion of the Palestinian independence movement, an indication that the government has given up its political program in favor of meaningless economic reforms. Forty-four years into the Israeli occupation of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, with a peace plan nowhere in sight, the Ramallah boom looks more like an attempt to placate a battle-worn Palestinian populace than to prepare for its independence. “It is a five-star occupation,” a skeptical Palestinian businessman named Sam Bahour told me. “It gives the impression to the outside world that everything is OK in Palestine”….

The Ramallah boom—which had perplexed and delighted and angered so many people in this tiny, contested strip of land—was the only instance of Westernized, highbrow normalcy in the whole of Palestinian life. Ramallah is the de facto capital of Palestine, but beneath that, it is something else: a place to pretend that one is no longer Palestinian.

Over the past few years, Ramallah’s building boom has become increasingly apparent — the city now has its own five-star hotel, the Mövenpick Ramallah, and there’s evidence of construction projects on every street. I had dinner one night at Orjuwan Lounge, a fusion of Mediterranean and Palestinian food, highlights that included shrimp prepared with a layer of falafel around them and drizzled in pomegranate syrup. It’s obviously a restaurant more geared toward foreigners in town for business or humanitarian missions than Palestinians, but the clientele wasn’t exclusively expat.

Pessimists fear that as Ramallah increasingly becomes the heart of modern Palestine, Palestinians are somehow relinquishing any claim to east Jerusalem. Others worry that the Ramallah boom is based on foreign aid that can’t possibly be sustainable in the long run (a fear that crystallized in 2012 when the US Congress cut off foreign aid to Palestine — the Obama administration quietly restored it in March), and it comes at the expense of the underdevelopment of the rest of the West Bank, to say nothing of the Gaza Strip. Compare, for example, Ramallah’s bustling street life to a street in Jericho, just a few kilometers east close to the Jordanian border.

It’s stunning that Ramallah lies just a few kilometers from Jerusalem, and it’s even more stunning that so few Israelis have ever set foot in Ramallah — that’s perhaps one reason why a final peace accord remains so elusive. Ramallah falls within ‘Area A’ of the West Bank, where Palestinian forces are largely responsible for security. Large, red ominous signs outside ‘Area A’ territories warn that it’s dangerous and illegal for Israelis to enter.

For all the political, cultural and linguistic differences between the West Bank and Israel, there are plenty of similarities. Israeli food and Palestinian food are essentially the same — and essentially the same as Lebanese food as well. Levantine cuisine is Levantine cuisine, folks, and falafel, hummus, labneh, pita and za’atar are just as ubiquitous in Ramallah as in Haifa, Tel Aviv and Jerusalem — or in Beirut, Saida or Tripoli. Prices, also, are oddly congruent — despite the fact that Israeli GDP per capita is around $31,000 and Palestinian GDP per capita is between $2,000 and $3,000, prices in Ramallah and throughout the West Bank may be slightly lower, but they certainly aren’t one-tenth those in Israel. (Just try to guess whether the falafel sandwich below is Israeli or Palestinian.*)

For all the glamour of modern-day Ramallah, there are reminders of the past — here, at Arafat Square, a monument to the first intifada symbolizes Palestine’s climb toward statehood.

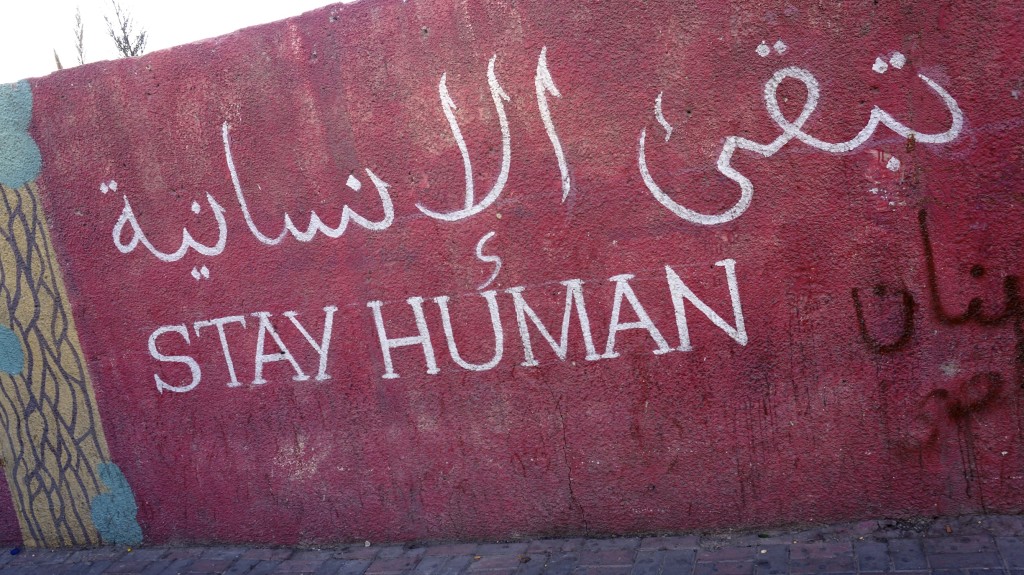

At the same time, you needn’t look too far to see both well-worn and new graffiti espousing the cause of Palestinian self-determination and an end to the Israeli occupation.

It’s hard to believe that Yasser Arafat has been gone for nearly a decade, and it’s even harder to believe that in Ramallah and the West Bank, given Arafat’s pervasive presence — it borders on personality cult. Arafat was the longtime chair of the Palestinian Liberation Organization from 1969 until his death in 2004 who led both the first and second intifada and came excruciatingly close to peace deals, first through the Oslo Peace Accords in 1993 with Israeli prime minister Yitzhak Rabin and again at the Camp David summit in 2000 with Israeli prime minister Ehud Barak. In contrast, it’s hard to find the same emblazoned presence for Arafat’s successor (and ostensibly the president of Palestine) Mahmoud Abbas.

Arafat’s death became especially controversial over the past two months, with dueling reports from Swiss and French scientist over whether Arafat’s death resulted from polonium poisoning. Here’s Arafat’s impressive grave at Muqata’a, the $40 million presidential palace, also recently built in Ramallah, that served as Arafat’s presidential compound in the West Bank, and increasingly his main headquarters in the final years of his life.

Psagot, a controversial Israeli settlement, lies just meters away from Ramallah at the top of a now quite foreboding hill. Established in 1981, it has a population of over 1,500 Israelis.

The Jamal Abdel Nasser Mosque in al-Bireh, named after the late Egyptian president, serves as another kind of reminder for the Israeli occupation — Israeli Defense Force troops gained control of the mosque in 2002 and killed four Palestinians from its minarets.

The ultimate symbol of the Israeli conflict, however, is perhaps Qalandia, one of the grimier checkpoints between the West Bank and Israel that feels more like a maximum-security prison more than a border crossing. Though I’ve written about the effects of Israel’s security wall strategy in the past decade, Qalandia is a sort-of free-for-all that reflects all the good and bad of Palestine — it’s sometimes a site of Palestinian attacks against Israel, but it’s more often a free-air market for traditional Arabic coffee (spiced with cardamom, of course), tea and other goods.

Waits can be lengthy, even for Palestinians who cross daily from the Ramallah side to the Israeli side, demonstrating the inefficiencies that even a booming Ramallah can’t fix. If that boom is a symbol of the best that Palestine could be, Qalandia is a reminder of all the hurdles that Palestine (and Israel) face before either side can achieve its political and economic potential.

* Trick question. The falafel in question actually came from Amioun, in the Greek Orthodox region of Koura in Lebanon.

Photo credit to Kevin Lees.

3 thoughts on “Photo essay: It’s clear that Ramallah is booming, but is it sustainable?”