The big story from the Argentine midterm elections is the rise of Sergio Massa as the frontrunner for the 2015 presidential election and the likelihood that the era of kirchnerismo is coming to an end. The fact that Argentine president Cristina Fernández de Kirchner has been absent from the campaign trail following emergency brain surgery earlier this month, which followed her party’s weak showing in August’s open primaries, only seemed to amplify the narrative that her presidency is entering its lame-duck phase.![]()

But amid the hype over Massa’s rise and the curtail calls for kirchnerismo, it may have escaped attention that Fernández de Kirchner’s ruling Frente para la Victoria (FpV, the Front for Victory) actually won Sunday’s midterm congressional elections.

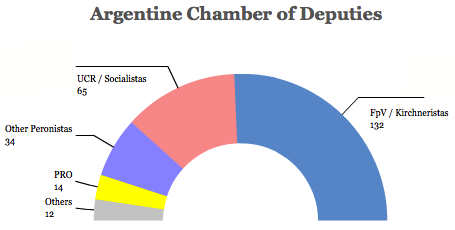

Voters elected one-half of the 257-member Cámara de Diputados (Chamber of Deputies), the lower house of the Argentine National Congress. Before the elections, Fernández de Kirchner and her allies control 132 seats — and that’s exactly the number they will control after the elections:

It helped that the Front for Victory was defending just 38 seats in the midterms, which certainly limited exposure and potentially greater losses for the kirchneristas. But make no mistake — Fernández de Kirchner and her allies will continue to control Argentina’s legislative branch for the final two years of her presidency, even if it will become trickier to pass bills into law.

In absolute votes, the Front for Victory and its kirchnerista allies far outpaced any other broad coalition of parties at the national level, winning 11 of the country’s 23 provinces:

Two other blocs each won about a quarter of the vote.

The first is comprised of alternative peronista groups. The original peronista party — the one that Juan Perón founded in 1947, is the Partido Justicialista (PJ, Justicialist Party), and it’s still part of the kirchnerista Front for Victory. But an increasing number of dissident peronista groups are forming in opposition to kirchnerismo, the largest of which is Massa’s Renewal Front. But despite its victory in Buenos Aires province, the Renewal Front won just 15.97% of the total national vote, and it has no political footprint in the other 22 provinces. Alternative peronista fronts won four additional provinces, including Córdoba, but they aren’t united in any formal manner.

The other bloc includes the remaining major national opposition parties, the center-right Unión Cívica Radical (UCR, Radical Civil Union), and the center-left Partido Socialista (PS, Socialist Party). The two parties often work together, however, on a province-by-province and election-by-election basis, and the two parties and their allies together won six provinces in the midterms, including Mendoza and Santa Fe.

Meanwhile, the conservative Propuesta Republicana (PRO, Republican Proposal) won the highest share of the votes within the autonomous city of Buenos Aires.

Voters also elected one-third of the 72-member Senado (Senate), the upper house and although the kirchneristas lost two seats, they will still control a majority — 39 senators.

Though it’s a far cry from the two-thirds majority that Fernández de Kirchner needed to amend the constitution and eliminate the term limits that otherwise forbid her to run for reelection, Sunday’s vote is still a decent result for a movement that’s held power in Argentina for 10 years. That’s especially true in light of a precarious economic situation — GDP growth is slowing, inflation remains a problem, the country remains shut out of world capital markets, and its foreign exchange system is broken.

But so long as Fernández de Kirchner can prevent further defections, the kirchneristas will still be able to pass legislation through the Congress, and while Fernández de Kirchner remains a lame-duck president, she’ll still be living in the Casa Rosada, Argentina’s presidential palace, for just over two more years. That’s a lot of time — for both the economy to stabilize or to worsen.

The fragmentation of the Argentine opposition is what kept the Kirchners in power in Argentina for so long — and it’s what propelled the little-known Néstor Kirchner, at the time a governor of the southern province of Santa Cruz, into the presidency in 2003. The 2015 presidential field is also likely to be fragmented. Massa is now almost certain to run, but so is Buenos Aires mayor and PRO leader Mauricio Macri, who celebrated his party’s victory Sunday night by announcing his 2015 presidential bid. Julio Cobos, a former Mendoza governor who served as vice president between 2007 and 2011 alongside Fernández de Kirchner, is now back in the UCR and won a deputy seat yesterday, paving the way for a potential presidential bid. Socialist Party leader Hermes Binner, a former governor of Santa Fe who also won a deputy seat, will likely repeat his 2011 presidential run.

That means that the right kirchnerista could potentially garner enough support in 2015 to win one of the two slots in a potential runoff. Buenos Aires province governor Daniel Scioli led the Front for Victory campaign in Fernández de Kirchner’s absence, though his party’s loss in the province won’t help his 2015 prospects. Two more popular options include Entre Ríos governor Sergio Urribarri and Chaco provincial leader Jorge Capitanich, both of whom led winning campaigns for the FpV in their respective states.