Voters in the heart of Atlantic Canada will go to the polls tomorrow to determine the fate of the first New Democratic provincial government in the history of the Maritimes. ![]()

![]()

Polls show that, under the weight of a patchy economy and low job creation, Nova Scotians will reject premier Darrell Dexter’s historic NDP government in favor of a Liberal Party government under Stephen McNeil — the Liberals hold a lead of between 15% and 20% in advance of the October 8 election, and voters prefer McNeil as Nova Scotia’s next premier by a slightly smaller margin.

While it may not be as populous as Ontario, Québec or British Columbia, Nova Scotia — with just under 3% of Canada’s population — is still the largest province in Atlantic Canada, which historically has a different cultural, political and economic orientation from the rest of Canada. With an economy that once roared in the 19th century (on the basis of shipbuilding and transatlantic trade), Atlantic Canada now features some of the most stagnant economies within Canada, and regional unemployment runs highest in the Maritimes. Despite some economic growth in Halifax, Nova Scotia’s capital and the largest metropolitan area in Atlantic Canada, the province’s 8.7% unemployment rate is still higher than Canada’s national 7.1% average.

Atlantic Canada, notably New Brunswick, was the last refuge of the old Progressive Conservative Party before it merged with Stephen Harper’s western-based Canadian Alliance in 2003 to form the Conservative Party that governs Canada today. In the 2001 federal Canadian election, the PCs won nine of their 12 seats in the House of Commons from within Atlantic Canada. Even today, Atlantic Canada remains home to a certain kind of Conservative politics — more moderate and less ideological — and the local center-right provincial party still calls itself the Progressive Conservative Party (remember that in Canada, there’s a brighter line between national and provincial political parties). Before Harper came to power in 2005, Tories placed their hope to retake national power in former New Brunswick premier Bernard Lord; Nova Scotia MP Peter MacKay led the PCs into their merger with the Alliance a decade ago, and he served as Harper’s defense minister for six years before a promotion this summer to justice minister.

The fate of the old Progressive Conservatives might have been foreboding to the national Liberal Party as well. In the most recent 2011 Canadian election, in which the once-mighty Liberals lost all but 34 of their seats in the House of Commons, the Liberals won 12 of them from Atlantic Canada — again, a party struggling for relevance nationally found refuge in the Maritimes. But while the Progressive Conservatives ultimately faded into Harper’s wider conservative movement, the election of Justin Trudeau as the party’s national leader earlier this transformed the Liberals from a spent, third-place political force into something like a government-in-waiting.

So even though Nova Scotia is small, it can also be a bellwether for larger trends.

While Trudeau’s leadership has breathed new life into the Liberal brand (even at the provincial level), McNeil and the Nova Scotia Liberals held a wide lead over the NDP in the province long before Trudeau’s national ascent. It’s a remarkable turnaround from the June 2009 provincial elections when the NDP swept to power with 45.24% of the vote, winning 31 out of the 52 seats in the Nova Scotia House of Assembly and ending a decade of Tory rule in the province — a victory that presaged the NDP’s 2011 federal breakthrough under its late leader Jack Layton.

Keeping all of that in mind, here are three areas to keep an eye on in the wake of tomorrow’s election that could presage trends over the next two years of Canadian politics more generally:

Forecasting a Liberal landslide: a lesson for pollsters.

It’s not been a great couple of years for pollsters in Canada, who famously botched forecasts of Alberta’s provincial election in April 2012 and, more recently, the provincial election in British Columbia in May 2013.

In Alberta, pollsters predicted that the long-running Progressive Conservative government would fall to an even more right-wing movement, the new Wildrose Party; on election night, however, Alberta premier Alison Redford won her first direct mandate in a landslide, taking 61 seats in the Albertan provincial assembly to just 17 for Wildrose.

In British Columbia, polls showed that the BC New Democrats, under leader Adrian Dix, held a significant (if shrinking) lead over the BC Liberals, who were seeking a fourth consecutive term in government under the untested leadership of premier Christy Clark. Clark and the BC Liberals not only survived, they improved their standing in the British Columbia legislative assembly by gaining four additional seats.

After both elections, pollsters suffered heavy criticism for getting the final results so wrong — in each case, not only did Wildrose (in Alberta) and the BC New Democrats fail to win as projected, but they actually lost ground against, respectively, the Alberta Progressive Conservatives and the BC Liberals.

The final ThreeHundredEight projection for Nova Scotia, based on the latest polling data, forecasts 48% for the Liberals, 29% for the NDP and 21% for the Progressive Conservatives. But a last-minute 10% swing from the Liberals to the Conservatives or back to the New Democrats, however, would make the race a tossup. For Canadian pollsters to botch three provincial elections on both the Pacific and Atlantic coasts of Canada in 18 months would seriously call into question their credibility with federal elections and Ontario provincial elections both due before 2015.

NDP/Liberal split: a lesson for the federal Liberals.

While the New Democrats have fallen behind the Liberals in Nova Scotia, they haven’t completely collapsed, and polls show that they retain significantly more support than the Tories within the province.

In the previous federal election, the result in Nova Scotia broke into a nearly a three-way tie: Conservatives, 36.7%; NDP, 30.3%; Liberals, 28.9%.

Put another way, both the result in the 2011 federal election and polling for the 2013 provincial election shows that the two parties on Canada’s left, the more progressive NDP and the more centrist Liberals, command an overwhelming majority of support from Nova Scotian voters.

In the federal election, the Tories and Liberals each won four seats, while the NDP won three. But the Tories won two of their four seats with less than 50% of the vote — and with less than the combined support of the NDP and Liberal candidates.

Given that the Nova Scotia election, like the federal election, is determined on a first-past-the-post basis in single-member districts, there’s a chance that centrist and center-left voters will split their support between the Liberals and the NDP, thereby resulting in relatively more seats for the Tories than they might otherwise have won in a straight two-way race.

Obviously, a similar dynamic is at work in federal politics — Trudeau has boosted the Liberals into first place nationally, but the NDP under its new leader Thomas Mulcair hasn’t collapsed. If the NDP/Liberal split is ultimately responsible for indirectly boosting the Tories at the provincial level, it will be a warning to both Trudeau and Mulcair that they could face a similar result in the more consequential federal elections. While neither Mulcair nor Trudeau are interested in a formal NDP/Liberal merger, it might be worth exploring an electoral pact in which the NDP and Liberals join forces in those federal ridings where a three-way split might inadvertently elect more Tories.

The anti-incumbency mood: a lesson for Harper.

In Alberta and in British Columbia, long-serving and often unpopular governments managed to cling to power on the basis of powerful economic growth fueled by the wealth of natural resources in western Canada. But the difference is that Nova Scotia’s economy is much weaker.

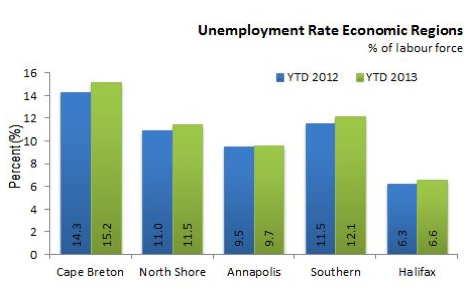

Voters appear likely to punish Dexter for failing to revive an economy that has flatlined outside of Halifax, resulting in a two-tier economy that’s relatively robust in Halifax and increasingly troubled in rural Nova Scotia, especially in the Cape Breton region. Compare the unemployment rates within Nova Scotia:

Canada’s national economic performance falls somewhere between the two extremes, and GDP growth is holding steady at an annual rate of around 2% since Harper was reelected in 2011. Although we don’t know the economic conditions that will underlie the next election, it seems unlikely that Canada will be either in boom mode or in bust mode. So if Dexter’s NDP government wins reelection, despite polling forecasts to the contrary, it could be a very good sign for Harper as he keeps one eye on 2015.

Photo credit to Kevin Lees — autumn outside Halifax, Nova Scotia, October 2010.

3 thoughts on “Three lessons that Nova Scotia’s provincial election can teach us about Canadian politics”