Just less than a month after Norwegians went to the polls, the contours of Norway’s new government are taking shape — and it’s not exactly what everyone expected.![]()

As widely anticipated, the leader of the center-right Høyre (literally the ‘Right,’ or more commonly, the Conservative Party), Erna Solberg, will become Norway’s next prime minister, but she’ll lead a minority government in coalition with just one of Norway’s three other political parties, the controversial anti-immigrant Framskrittspartiet (Progress Party) after two smaller center-right parties pulled out of coalition talks earlier this week.

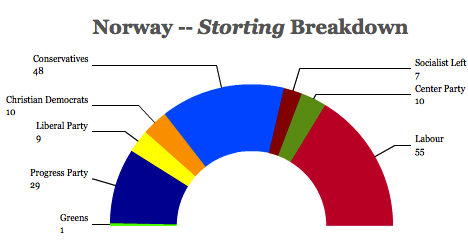

The difference is that instead of a 96-seat majority in the 169-member Storting, Norway’s parliament, Solberg’s government will hold just 77 seats, eight short of an absolute majority:

I wrote before the election that pulling together all four parties on the Norwegian right might prove problematic. Sure enough, both the Kristelig Folkeparti (Christian Democratic Party) and Venstre (literally, ‘the Left,’ but commonly known as the Liberal Party), which will hold 10 and nine seats, respectively, in the next parliament, will not join the government. Though both parties have agreed to provide support to Solberg (pictured above) from outside the government, it’s not an auspicious start for the broad four-party coalition that Solberg hoped to build after last month’s victory. The absence of the Christian Democrats is particularly difficult, given that they led the last center-right Norwegian government — that of prime minister Kjell Magne Bondevik between 1997 and 2000 and 2001 to 2005.

The Progress Party, meanwhile, will enter government for the first time since its foundation in the 1970s. Founded as an anti-tax movement determined to roll back the Norwegian social welfare state, the Progress Party has also become increasingly anti-immigrant. While it’s certainly tame compared to many of Europe’s more xenophobic anti-immigrant parties, it’s easily the most controversial party in Norway (not least because mass killer Anders Behring Breivik was once among its members). Anxiety about the Progress Party’s new, unprecedented role in government is one of the reasons that the Christian Democrats and Liberals may have been wary of formally joining Solberg’s coalition, which will now become Norway’s most right-wing government in a century.

Solberg, on the other hand, slowly gained the trust of Norwegians after rebranding the Conservatives into a more welcoming, more national party that’s transcended its base catering to business interests in Oslo. Although the Conservatives and the Progress Party agree on economic policies like tax cuts, the Conservatives have positioned themselves as an ever-so-slightly right-of-center party who would leave in place much of the mainstream policy preferences of the outgoing center-left Arbeiderpartiet (Labour Party) — you can characterize ‘mainstream’ in Norway as full commitment to a generous social welfare state, mixed with strict fiscal discipline that diverts much of Norway’s oil largesse into its $780 billion investment fund, the world’s largest sovereign wealth fund.

Given that the Labour Party, led by the popular outgoing prime minister Jens Stoltenberg, still managed to win more votes than any other party — and seven more parliamentary seats than the Conservatives — last month (a feat Labour has repeated in every national election since 1918), that’s a wise move on Solberg’s part. But balancing the moderation that Norwegians expect from her with the Progress Party’s expectations was always going to be difficult, and Solberg’s dream of a broad four-party coalition will be the first casualty of those competing expectations.

That balancing act informs much of the resulting agreement between the Conservatives and Progress and, more generally, among the four right-wing parties that Solberg will need to satisfy to keep her minority coalition in government — it’s more notable for what the government won’t do than what it will. The government faces a much different challenge than the rest of Europe — with GDP growth holding steady at around 2%, it’s overheating, not recession, that threatens the economy. Solberg’s challenge is how to keep the Norwegian krone from further appreciating, given that the country’s high wages are already making exports less competitive.

Notwithstanding the election campaign, lowering the value of the krone might ultimately be the Solberg’s most pressing policy imperative.

Here are the highlights of how Norway’s next government will unfold under Solberg’s leadership: Continue reading Norway’s new government will be more right-wing and more fragile than expected