One year into the minority government of Québec premier Pauline Marois, the province is again at the center of controversy with a new attempt to legislate a ‘charter of Québec values’ that’s drawing ire from the rest of Canada. ![]()

![]()

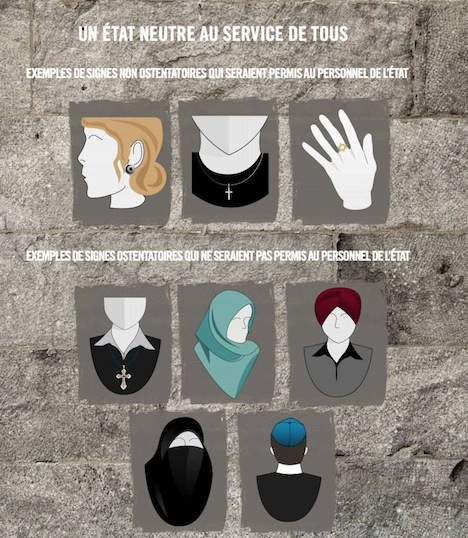

That chart above isn’t a joke — it was released yesterday by Québec’s government, and it purports to demonstrate examples of ‘non-ostentatious’ signs that state employees are permitted to wear.

You’ll note that two-thirds of ‘approved’ examples are Judeo-Christian religions and three-fifths of the ‘banned’ examples are not. The ‘secular charter’ (la charte de la laïcité) would ban public sector workers from wearing kippas, turbans, burkas, hijabs or ‘large’ crucifixes. Remember that in Québec, the public sector is quite expansive, so the charter would capture not only folks like teachers, police and civil servants, but employees in Québec’s universities and health care sector as well.

For good measure, the proposed charter would also tweak Québec’s Charter of Human Rights and Freedoms to limit religious exemptions, though it wouldn’t eliminate subsidies to religious private schools in Québec that are largely Catholic and largely funded by the state and it wouldn’t eliminate property tax exemptions for churches and other religious buildings.

In short, the charter looks less like a secular bill of rights than a sop to French Canadians to perpetuate preferred legal and cultural benefits at the expense of other ethnic and religious groups — tellingly, the crucifix hanging in Québec’s provincial assembly would be exempt from the law. A charter that, at face value, purports to secularize Québec’s society, would actually enshrine the dominant Catholic French Canadian culture and exclude Canada’s growing global immigrant population from many of the religious freedoms typically associated with a liberal democracy. If passed into law, it would conflict with the religious freedom guaranteed in Canada’s Charter of Rights and Freedoms (essentially, Canada’s bill of rights) — Québec did not sign the federal Charter, nor did it approve of the 1982 constitutional settlement, but remains subject to the federal Charter. That means the ‘secular charter’ could once again put Québec on a collision course with the rest of Canada.

It’s also the latest salvo in a series of only-in-Québec culture-war misfires that have plagued the Marois government since it took power last year, and it goes a long way to explaining why Marois and the sovereignist Parti québécois (PQ) are in danger of losing the next election.

Over the past year, it would have been enough for Marois to declare victory on the issue of student fees and largely pacifying student protests, to declare that her government would largely continue Charest’s Plan Nord, a push to develop Québec’s far north in pursuit of resources over the coming decades, and to focus on bringing investment and jobs to Québec. Marois’s government has also pushed to end support for Québec’s notorious asbestos industry, winning plaudits from environmentalists.

But if you want to know why Marois’s minority government isn’t in a more commanding position, it’s because it has pursued language and culture legislation as a time when Québec, which wasn’t exactly Canada’s most growth-oriented province to begin with (its per-capita GDP of around CAD$43,400 is CAD$5,500 less than neighboring Ontario’s and a staggering CAD$35,000 less than resource-rich Alberta), is falling behind the rest of Canada.

Between August 2012 and August 2013, Canada’s unemployment rate has dropped from 7.8% to 7.6%, but in Québec, the unemployment rate rose from 7.8% to 8.1%.

Instead, her government has plunged Québec back into the language wars, drawing ridiculous global headlines — a great example is the crackdown of the Office québécois de la langue française against a Montréal Italian restaurant’s use of the word ‘pasta’ and other Italian words on its menu and demanding the restaurant print their French equivalents more prominently. (Though we all know that apéritif or hors-d’œuvre is not the same thing as antipasto are not the same thing).

It comes after the Marois government has largely given up its year-long fight to pass Bill 14, which would amend Québec’s La charte de la langue française (Charter of the French Language, also known as ‘Bill 101’) by allowing the government to revoke a provincial municipality’s bilingual status if the anglophone population falls below 50%, requiring small businesses (of between 26 and 49 people) to use French as their everyday workplace language, and mandating that all businesses that serve the public use French with customers.

Marois switched gears from the language charter to a new religious charter when it became clear that her minority government would have a hard time pushing Bill 14 through, but also because a ban on religious symbols is relatively popular among the Québécois electorate.

A recent Léger Marketing poll taken at the end of August showed the Liberals with 36%, the PQ with 32% and 18% for the Coalition avenir Québec (CAQ), a right-leaning coalition that draws support from around Québec City and takes a middle-road ‘autonomist’ position between sovereignists and federalists in Québec. It and other polls generally show the PQ doing somewhat better than earlier in the summer, when the Parti libéral du Québec (Liberal Party, or PLQ), held a double-digit lead. But the PQ remains in a far from envious position — when it narrowly won a minority government a year ago, Marois had hoped to quickly consolidate the party’s gains and win a mandate for a majority government soon thereafter.

But the PQ’s victory against the Liberals in the September 2012 provincial elections was incredibly unimpressive — the PQ won just 54 seats in the 125-seat Assemblée nationale, giving Marois a relatively weak minority government.

That’s despite the fact that Québec’s then-premier Jean Charest had become a massively unpopular incumbent, despite the fact that the Liberal Party was seeking a fourth consecutive mandate, despite the fact that the Liberal Party was running under a cloud of investigation for corruption accusations and despite the fact that Charest’s government responded poorly to student strikes against planned tuition increases with a draconian emergency bill that gave police extraordinary powers to crack down on students. As it turns out, Charest’s Liberals won 50 seats and nearly as much support as the PQ.

Meanwhile, Québec’s Liberal Party has a new, competent leader in Philippe Couillard, a Montréal neurosurgeon and former minister of health and social services, whose most important qualification for becoming Québec’s next premier is that he’s not Jean Charest.

All of which means Marois faces an election sooner rather than later — and that the PQ is not in an ideal position to win it.

Though the secular charter may have been initially popular, Marois may not have counted on an international backlash against the proposal, including some harsh criticism from all of Canada’s major federal parties — and even some of Québec’s leading sovereignists. Thomas Mulcair, who leads the New Democratic Party (NDP) that holds 59 out of Québec’s 75 seats to the House of Commons, slammed the proposal in uncharacteristically harsh terms. Justin Trudeau, the magically popular leader of the federal Liberal Party of Canada (which has ties to, but isn’t formally linked to the provincial Liberal Party), also heaped stinging criticism upon the charter proposal:

“Madame Marois has a plan. She has an agenda. She’s trying to play divisive identity politics because it seems to be the only thing that is able to distract from the serious economic challenges that we’re facing as a province and as a country,” Trudeau said.

Conservative prime minister Stephen Harper may challenge the charter in court, if it’s passed into law, as unconstitutional — that’s controversial because it could reopen the constitutional battles that roiled Conservative prime minister Brian Mulroney in the 1980s and led to a wave of separatism that nearly won an independence referendum in September 1995.

But Marois is hardly in as strong a position as Québec’s past generation of sovereignists, and although her latest push is smart politics among francophone voters, it’s difficult to see Marois successfully waging another zero-sum battle with Canadian federalists. The charter is not without controversy even among sovereignists — Françoise David, the leader of the leftist Québec solidaire, another sovereignist party, has come out very much in opposition to the new charter.