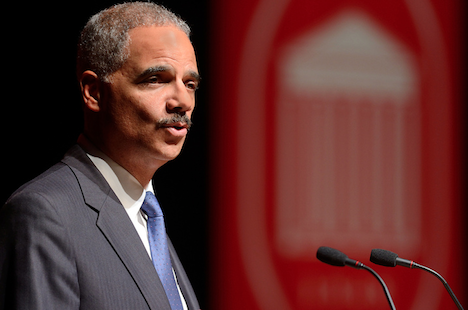

As U.S. attorney general Eric Holder makes a serious push for prison and justice reform in the United States, he would do well to look at a similar push across the Atlantic — Kenneth Clarke’s attempt to reverse decades of tough criminal law policies in the United Kingdom provides a cautionary tale.![]()

![]()

Holder announced yesterday in a speech to the American Bar Association that the U.S. justice department will seek to avoid mandatory sentences for non-violent, low-level drug-related offenses, and justice reform advocates largely cheered a welcome pivot from the ‘tough-on-crime’ approach to justice that’s marked U.S. policy for the past four decades throughout much of the ‘War on Drugs’ — drug-related offenses have largely fueled the explosion in the U.S. prison population. Holder will instruct prosecutors in federal cases not to list the amount of drugs in indictments for such non-violent drug offenses, thereby evading the mandatory sentences judges would otherwise be forced to administer under federal sentencing guidelines. That’s only a small number of prisoners because 86% of the U.S. prison population is incarcerated by state government and not by the federal government.

Holder called for ‘sweeping, systemic changes’ to the American justice system yesterday and attacked mandatory minimum sentences for non-violent offenders, which he said caused ‘too many Americans go to too many prisons for far too long and for no good law enforcement reason.’

That approach has left the United States with a prison population of nearly 2.5 million people (though the absolute number has declined slightly after peaking in 2008) and the world’s highest incarceration rate of 716 prisoners per 100,000 . That’s more than Russia (484), Brazil (274) the People’s Republic of China (170) or England and Wales (148) and as Holder noted yesterday, the United States has 5% of the world’s population but 25% of the world’s prisoners.

Particularly damning to the United States is that 39.4% of all U.S. inmates are black and 20.6% are Latino, despite the fact that black Americans comprise just 13% of the U.S. population and Latinos comprise just 16%. Holder yesterday cited a report showing that black convicts receive prison sentences that are around 20% longer than white convicts who commit the same crime. Holder denounced mandatory minimums as ‘draconian,’ and made an eloquent case that U.S. enforcement priorities have had ‘a destabilizing effect on particular communities, largely poor and of color,’ that have been counterproductive in many cases. Holder also made that case that in an era of budget cuts, America’s incarceration rate is a financial burden of up to $80 billion a year, and that reducing the U.S. prisoner population could shore up the country’s finances as well.

But Holder — and prison reform advocates that have emerged on both the American left and right — face a heavy task in reversing nearly a half-century of crime legislation that has largely ratcheted up, not down.

Just ask Kenneth Clarke, who until last September was the justice minister in UK prime minister David Cameron’s coalition government, who as one of the longest-serving and most effective Tories in government for the past four decades, faced a tough road in enacting prison reform in England and Wales.

Though its prison population and incarceration rate pales in comparison to that of the United States, the British justice system imprisons more offenders than many other countries in the European Union, such as France (101 prisoners per 100,000) or Germany (80).

Cameron faced a delicate task in finding a role for Clarke in his government back in mid-2010. Clarke, a self-proclaimed ‘big beast’ of Tory politics got his start under ‘one nation Tory’ prime minister Edward Heath and found his stride under Heath’s successor, Margaret Thatcher. He became John Major’s chancellor of the exchequer, guiding No. 11 from the dark days of the 1992 ‘Black Wednesday’ sterling crisis to a more robust financial position. When Labour swept to power in May 1997 under Tony Blair, Clarke immediately became the most popular Conservative in the country, even though the significantly more right-wing and increasingly euroskpetic party thrice denied the pro-Europe Clarke its leadership. While Clarke may have passed his glory days in government, his appointment as justice minister reflected that Clarke could still be useful in government.

Clarke’s biggest target as justice minister? Reducing the number of offenders in English prisons and attacking what Clarke memorably called the ‘Victorian bang-’em-up prison culture’ in a landmark June 2010 speech: Continue reading Clarke’s British reform failures a lesson as Holder pushes for historic turn on U.S. crime