Though he’s making headlines this week for his stunt as a barely-disguised cab driver cruising the streets of Oslo to get a sense of the frustrations of Norwegian voters less than a month before Norway’s parliamentary elections, prime minister Jens Stoltenberg has long seemed destined to lose the September 9 vote. ![]()

Stoltenberg, who leads the Arbeiderpartiet (Labour Party) and has served as Norway’s prime minister since 2005, is running for a third consecutive term, and poll shave consistently shown his party running behind the Høyre (literally the ‘Right,’ or Conservative Party), and Norway has braced throughout the year for the likelihood that its voters will elect a center-right government. It’s not unprecedented for Norway to have a right-leaning government — most recently, the Conservatives were part of a governing coalition led by Kjell Magne Bondevik and the Kristelig Folkeparti (Christian People’s Party) from 2001 to 2005. But if polls today are correct, the Conservative Party will actually win more votes than the long-dominant Labour Party, and therefore hold more seats in the Storting, Norway’s parliament, and that hasn’t happened in a Norwegian election since 1924.

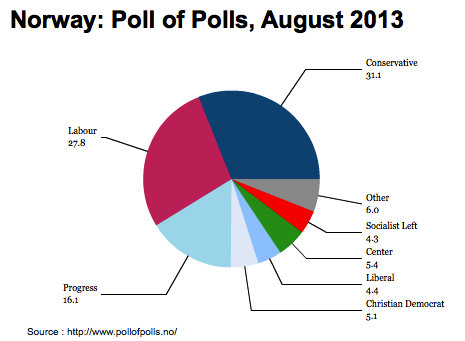

But the polls are narrowing — the Conservative Party still leads the Labor Party, and taken together, the broad center-right parties expected to form Norway’s next government hold a double-digit lead over the broad center-left parties that currently comprise Stoltenberg’s governing coalition. One recent poll from TNS Gallup over the weekend showed the Conservatives with just 31.6% to 30.1% for Labour, much narrower than the five-point lead the Conservatives held only in July. Here’s the latest August poll-of-polls data:

As I wrote earlier this summer, Erna Solberg, the leader of the Conservative Party since 2004, became the frontrunner in next month’s elections by rebranding the Conservatives as an acceptably moderate alternative to Labour. In many ways, Solberg’s Conservatives today share more in common with Labour than with their largest presumptive coalition partner, the more populist, far-right Framskrittspartiet (Progress Party), a party. But there’s still more or less a month to go before voting begins, and many Norwegians are still focused on their summer holidays than on the late-summer campaign. That means there’s more than enough time for Labour to make up the difference before September 9.

While that doesn’t necessarily mean that Labour will return to government, it does mean that Labour has a shot at retaining its place as the largest parliamentary party in Norway and, in a best-case scenario, could potentially form a new, broader coalition, perhaps even with the Conservatives, to keep the Progress Party out of government.

Here are four reasons why that outcome isn’t as farfetched as it seems:

Norway has one of the strongest economies on the planet

Norway’s economy is booming these days — at least by European standards. With a GDP per capita of over $60,000, Norwegian standards of living have now far eclipsed those in Sweden, from which Norway broke away in 1905. Norway’s GDP growth bounced back from a mild contraction in 2009 to 1.4% in 2011 and an estimated 3% to 3.5% last year. But what would feel like a boom nearly anywhere else in Europe now feels like a slowdown in Norway. Although its unemployment rate was just 3.4% as of June 2013, Norway has more unemployed citizens today than at anytime in the past eight years and the economy is expected to slow this year — it is forecast to grow between just 2.5% to 3% this year.

Norway’s oil wealth had freed it from the debt burdens with which many other European nations have struggled, and Norway has balanced its budget for the past two decades, with plenty to spare. Norway routinely reinvests its surplus in its sovereign wealth fund — in 2012, that was equal to around 15% of GDP, and the fund’s size has quadrupled since Stoltenberg took office in 2005. Nonetheless, Stoltenberg’s government has increased the government’s expenditures by 19% this year, largely by pulling on the vast wealth set aside by previous governments in the hopes that a push to boost health and welfare spending will compensate for the slack in Norway’s economy, especially in an election year.

Doubts about the Progress Party in government

Solberg and the Conservatives are in such a strong position today largely by stealing away supporters of the Progress Party, which won 22.9% of the vote in the previous September 2009 elections and is currently the second-largest party in parliament. But the party’s support has fallen due to its ties to Anders Behring Breivik, a one-time Progress Party member responsible for two nearly simultaneous attacks in July 2011 — bombings in Oslo and a shooting at a Labour Party youth camp that killed 77 people.

Unlike several far-right European parties, the Progress Party’s roots do not lie in the anti-immigration movement, but date back to the anti-tax movement of the 1970s. To be sure, the party is staunchly anti-Islam and opposed to immigration, but it’s even more animated by its project to dismantle Norway’s social welfare state and to cut taxes and government regulation, which isolates it among the rest of Norway’s political parties on the left and on the right. Its populist bent means that it’s called for the state to spend more of its oil largesse rather than reinvesting it in Norway’s sovereign wealth fund.

But the Breivik attacks severely hurt the party’s image, despite leader Siv Jensen’s attempts to distance the party from the evil actions of a lone criminal. More than two years later, however, Progress is set to become the biggest loser in the 2013 elections — although it may win 15% or 16% of the vote, that’s a drop of up to 8% from its 2009 performance.

Moreover, the Progress Party has never participated in the previous center-right coalitions in Norway’s recent history, which means that it’s never entered Norwegian government. As September approaches, voters that nominally favor the Conservatives over Labour may think twice about the consequences of putting the Progress Party into power, which would potentially make Jensen Norway’s new finance minister. That is sure to lead to some cultural differences with the Conservatives, who draw much of their support from urban centers like Oslo, who support same-sex marriage, immigration and even European Union membership (Norway rejected EU membership in two referenda in 1972 and 1994). Most fundamentally, however, the Conservatives wish to reform Norway’s social welfare system, not destroy it.

Stoltenberg’s popularity and Labor’s historical advantage.

Though Stoltenberg’s job approval sank to just 36% in June, down from a high of 94% approval in the aftermath of 2011’s dual attacks, his personal popularity remains high as a prime minister, not only due to his response to the Breivik attacks — he’s a relatively charismatic and understated leader, which comes through in his offbeat turn as a cab driver on Saturday. Formerly Norway’s finance minister in the 1990s, he’s generally seen as a capable steward of the Norwegian economy who has guided Norway through the worst shocks of the 2008-09 financial crisis.

There’s every reason to believe that his underlying popularity will allow him to win back voters who now say they are supporting Solberg, who’s run a gauzy campaign based on slogans like like ‘Mennesker, ikke milliarder,’ or ‘human beings, not billions.’ If Stoltenberg can convince voters that the ‘change’ Solberg is promising is really just a pale replication of Labour’s longstanding economic and social welfare policies, he can argue that supporting Labour is the safer choice for disaffected Labour voters who might support Solberg in the abstract, but fear bringing the Progress Party to power.

There’s also every reason to believe that Labour, with its longstanding grip on Norwegian politics, will find a way to energize its base in the weeks ahead. Even in 2001, when the party suffered its worst defeat since its rise to prominence in the 1920s, it managed to win 24.3% of the vote and 43 seats to just 38 for the Conservatives.

Growing strength of Labour’s Red-Green Coalition allies.

Since returning to power in 2005, Labour has governed with two much smaller allies as part of a ‘Red-Green coalition’ — the ‘red’ member is the democratic socialist Sosialistisk Venstreparti (Socialist Left Party) and the ‘green’ member (‘green’ for its agrarian roots, not its environmental policy) is the Senterpartiet (Centre Party), a rural party that has moved firmly to the left in recent years.

Between July and August, for example, the Socialist Left jumped from below 3.9% up to 4.3% — that’s important because under Norway’s electoral system, 4% is the electoral threshold to win so-called ‘leveling’ seats that ensures representation in the Storting. In August, the Center Party jumped to 5.4% from 4.6% in July — while that’s not a massive jump, it’s enough to boost the ranks of Labour’s smaller partners. When translated into seats in parliament, the small boost for the two small parties means a jump from nine seats to 17 seats, and given that there are only 161 seats in the unicameral parliament, that makes a huge difference.

Over the same period, all of the potential members of the center-right coalition dropped slightly or gained no support — and the smallest of the potential center-right allies, Venstre (the Liberal Party) dropped from 5.2% to 4.4%.

2 thoughts on “Four reasons why cab-driving Stoltenberg has a chance at winning Norway’s election”