Norway kicks off a busy month of elections in Europe with parliamentary elections on September 9, and if the past year’s worth of polls are to be trusted, Norwegians seem set to take a right turn, despite one of the best economies in Europe. ![]()

If they do so, Norway is likely to have only the second female prime minister in its history — Erna Solberg, who since 2004 has been the leader of the Høyre (literally the ‘Right,’ or more commonly, the Conservative Party).

With less than two months to go, Solberg’s Conservatives have built a growing and steady lead over the governing Arbeiderpartiet (Labour Party) and prime minister Jens Stoltenberg, a popular prime minister who’s governed Norway since 2005.

A familiar face as the Conservative leader for nearly a decade, Solberg served previously as a minister of local government and regional development from 2001 to 2005 in Norway’s previous center-right government, a role that earned her the nickname of ‘Jern-Erna,’ or ‘Iron Erna,’ and she bears some similarity to the other, more familiar center-right leader who’s running for reelection in September as well (catch an English interview with Solberg from April on the U.S.-based CNBC here).

Winning a third consecutive term in office is difficult for any government because, as years go by, the front line of policymakers either leave government or become increasingly fatigued, and governing parties, who have an increasing political stake in the status quo, don’t often regenerate the same quality of new ideas that outside parties do while in opposition.

But it’s hard to understand just why Labour seems so likely headed out of government, especially in light of Stoltenberg’s continued popularity. It’s even more baffling when you consider that Norway is one of the best governed states in Europe, let alone the world. Despite the fact that most of Europe is in recession or zero-growth mode, Norway grew by an estimated 3% in 2012, and the unemployment rate is a laughably low 3.5%. Thanks to its oil wealth, it has had balanced budgets for nearly two decades, the government routinely banks its surplus (an estimated 15% of GDP in 2012) in investment funds for future use, and Norway’s GDP per capita now exceeds $60,000.

That leads to two questions: why are Norwegian voters so adamant about voting out its current government? And how did Solberg and the Conservatives become such clear frontrunners?

Background: politics in the Stoltenberg era

The 2005 election (and the ensuing 2009 election) brought about the balance that’s largely held steady for the past eight years. Stoltenberg currently governs with the support of a ‘Red-Green’ coalition dominated by Labour and its two smaller allies, the democratic socialist Sosialistisk Venstreparti (Socialist Left Party) and the Senterpartiet (Centre Party), a chiefly agrarian party that’s moved from the political right to the political left in recent years. Note that ‘green’ in Norway’s Red-Green coalition indicates the Center Party’s roots in rural life, not its environmental activism.

The 2005 fall of the previous center-right government of prime minster Kjell Magne Bondevik brought a drop in support for both Kristelig Folkeparti (Christian Democratic Party) and his coalition partners, the Conservatives. That left the Framskrittspartiet (Progress Party), a relatively populist party known chiefly for its opposition to much of the Norwegian social welfare state, its advocacy of lower taxes, smaller government and deregulation, and its controversial anti-immigration stance, as the second-largest party in Norway’s parliament. Unlike Labour and the Conservatives, both of which were founded in the late 19th century, the Progress Party emerged only in the 1970s as a modern conservative anti-tax movement. Though it’s grown to become a major force in Norwegian politics over the 1990s and 20o0s, Progress has never formally joined any government, though that seems likely to change, as Solberg is expected to bring Progress into government if her party maintains its polling lead on September 9.

Though if Solberg’s Conservatives win their expected landslide, they will do so in large part by consolidating left-leaning moderates that have supported Labour and right-leaning moderates that have supported Progress.

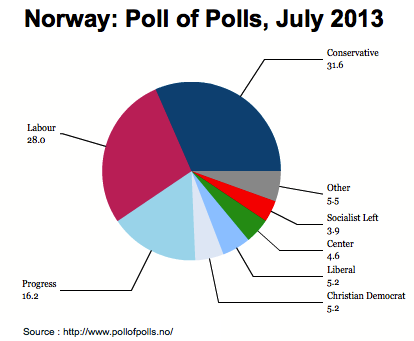

The latest July 2013 poll-of-polls shows the Conservatives with nearly 32% of the vote, which would give them around 58 seats in the Storting, Norway’s unicameral 169-seat parliament:

That’s a huge jump from the 30 seats the Conservatives hold now, and it’s a massive jump from their 2005 debacle, when they won just 14.1% of the vote and a measly 23 seats.

Even more striking is that Labour might not win the largest plurality of votes and the largest bloc of seats in parliament — for the first time since 1924.

How the Conservatives edged out the other center-right parties

Attrition and time spent outside government have much to do with the party’s turnaround, of course, but there’s no magical law that dictated that the Conservatives would be the center-right party to take the frontrunner mantle when voters invariably tired of Stoltenberg’s government. To some degree, the Conservatives have benefitted from the problems of their center-right rivals. Since the end of Bondevik government, the Christian Democrats have been hopelessly divided between a more secular liberal branch and a more social conservative branch. Meanwhile, the Progress Party has fallen in support since the 2009 parliamentary elections, and it took huge losses in 2011 local elections, in large part due to its connection to Anders Behring Breivik, the former Progress Party member who executed nearly simultaneous July 2011 terrorist attacks on both Oslo’s government quarter and a Labour Party youth summer camp.

But the Conservatives are on the cusp of winning power in Norway in large part due to their own efforts.

Today’s Høyre has positioned itself as a moderate alternative to Labour: it’s a vote for gradual reform and fiscal adjustment while also continuing or enhancing the budget discipline of Stoltenberg’s current administration, all without sacrificing Norway’s tradition of social liberalism and without embracing the Progress Party’s more controversial anti-Muslim views.

Unlike Progress and the Christian Democrats, the Conservatives have an urban base, and they have long been popular among the wealthy and business elite in Oslo and other large Norwegian cities in the country’s south, with only minor support in the more rural coastal and northern parts of the country, giving them a somewhat cosmopolitan flair.

In recent years, however, Solberg and her allies have pushed to make the party seem even more inclusive with respect to both economic and social policy. Her party, alone among Norway’s center-right parties, supported the landmark gay marriage and adoption bill in 2008 that led to Norway becoming the sixth nation in the world to recognize same-sex marriage. Solberg has rebranded the Conservatives with slogans like ‘Mennesker, ikke milliarder,’ or ‘human beings, not billions.’

The key to Solberg’s success has been knowing when to prioritize reform and when to prioritize continuity. So like Labour (and unlike Progress), the Conservatives are more or less in favor of perpetuating the Norwegian social welfare system. Like Progress (and unlike Labour), the Conservatives are pushing for lower taxes, and they have called for reforms to the welfare system to encourage more entrepreneurship and less dependence on oil wealth.

Solberg has also neutralized one of her party’s most unpopular positions — like Labour (and unlike Progress, the Christian Democrats or either of Labour’s Red-Green allies), the Conservatives are also in favor of European Union membership. But Solberg has promised that she won’t seek an EU membership referendum if she becomes prime minister in September. Though Norway is part of the European Economic Area, a broad arrangement that allows Norway, Liechtenstein and Iceland to be part of the European Union’s single market without having EU membership, there’s very little appetite today in Norway to join the European Union. Despite a 1994 referendum in which almost 48% of Norwegian voters opted to join, polls show that EU membership today is very unpopular, with over 70% of Norwegians opposed to joining a union that many Norwegians believe would drag their standard of living lower. EU membership is, in essence, so unpopular among Norwegians, that it’s become easy for Solberg to abandon it as an unreasonable goal.

Taking on Labour’s historical hegemony in Norwegian politics

Historically, the Labour Party has dominated Norwegian government and politics since before World War II — it has governed the country for all but 16 years since 1935 and it has won the largest plurality of votes in every consecutive parliamentary election since 1924. The Labour Party was responsible for the high-tax, high-benefit social welfare model that’s prevalent throughout Scandinavia and that’s generally accepted by most mainstream Norwegian political parties on all sides of the ideological spectrum (excepting Progress): free universal health care, nearly free universal education, nearly a year of paid parental leave, and significant other social benefits. Norway’s social welfare system, in particular, has become even more enshrined as public policy since the discovery of Norwegian offshore oil in 1969.

That means that Norway has only experienced two major episodes of center-right government since the 1970s.

The first was the Conservative-led government of Kåre Willoch of the 1980s, which came to office in 1981 with a mandate for cutting taxes, permitting greater private participation in broadcasting and deregulating what had become a highly statist economy. Though Willoch held onto power after the 1985 parliamentary elections, a financial crisis and faltering support from Willoch’s coalition allies, the Christian Democrats and the Centre Party, eventually caused his government to fall in 1986.

The more recent center-right government was that of Christian Democratic prime minister Kjell Magne Bondevik, who served from 1997 to 2005, minus a 19-month stint in opposition when Stoltenberg led a brief center-left government from 2000 to 2001. Bondevik’s government included the Centre Party and, after 2001, the Conservatives. The Progress Party never formally join Bondevik’s government, but it often supported his legislation from outside the coalition.

2 thoughts on “How Erna Solberg became the frontrunner in Norway’s upcoming election”