After nearly a decade in opposition, the newly united Albanian left is favored to defeat the incumbent center-right government of prime minister Sali Berisha with just days to go until the country’s June 23 parliamentary elections.![]()

A country of about 3.5 million residents, tucked on the southeastern Adriatic coast and bounded by the floundering Greece to its southeast, troubled Kosovo to its northeast with Montenegro to its northwest, Albania is the only country outside of the former Yugoslavia federation to have missed the first wave of European Union expansion in southeastern Europe. Unlike neighboring Serbia, Macedonia and Montenegro (or even, officially, Turkey), Albania is not yet even an official candidate for EU membership, following an embarrassing rejection in 2010 of its application for candidate status.

Regardless of who wins Albania’s elections, the world — and especially the European Union — will be watching keenly to gauge whether Albania’s government can conduct free and fair elections and orchestrate a seamless transfer of power if, as expected, it is voted out of office. Though Albanian elections have become steadily fairer in the two decades since the country emerged from one-party rule, standards fall somewhat behind those within EU members, including most recently in 2011 local elections that resulted in charges of fraud and incompetence. Moreover, Berisha has increasingly tried to use pan-Albanian nationalism to rally supporters, and he has even tried to extend suffrage to ethnic Albanians in Kosovo, none of which has endeared Albania’s current government to European policymakers.

After eight years in power, Berisha’s government has some modest accomplishments to boast for itself, despite its failure to get Brussels to take its EU aspirations seriously. Berisha forged strong ties with the United States, hosting the first U.S. presidential visit to the country in 2007, and he helped shepherd Albania into the North Atlantic Treaty Organization in 2009. Berisha has also presided over steady GDP growth rates of between 5% and 7% before the global financial crisis and between 3% and 5% from 2009 through 2011.

Berisha leads the Partia Demokratike e Shqipërisë (PD, Democratic Party of Albania), the country’s largest conservative party and the most dominant member of a wider coalition of parties (the so-called Alliance for Employment, Prosperity and Integration) contesting the parliamentary elections. The PD-dominated coalition currently controls 69 seats in the 140-member, unicameral Albanian parliament (Kuvendi).

But because Albania depends on Italy to purchase nearly half of its exports, it’s not a surprise that growth dropped to just 1% in 2012, with forecasts to remain tepid in 2013. After nearly two decades of growth after Albania emerged from its statist, Soviet-era economy, that has felt like recession for most Albanians, and that’s one of the reasons that both major parties in Albania are campaigning on the theme of change in 2013. It’s also one of the reasons that the country’s main center-left party, the Partia Socialiste e Shqipërisë (PS, Socialist Party of Albania) and its alliance with a handful of smaller leftist parties (the Alliance for a European Albania) seems very likely to win the elections — the PS has held has held a consistent, if narrow, lead throughout the election campaign. The PS and its allies currently hold 61 seats in Albania’s parliament.

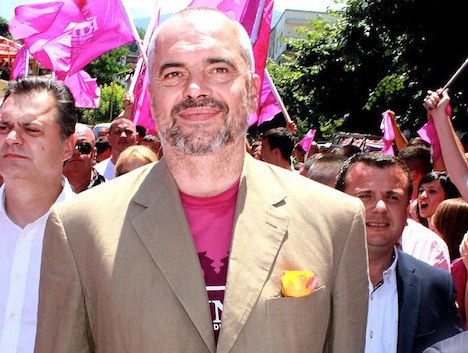

Its leader, Edi Rama, is a former artist who served as mayor of Albania’s capital and largest city, Tirana, from 2000 until 2011, when Rama lost a reelection bid by the narrowest of margins in a vote that made European leaders doubt the ability of Albanian institutions to carry out fair elections. Rama has run a thoroughly modern campaign, and he’s even expected to offer an advisory role to former UK prime minister Tony Blair if elected, which may well help accelerate Albania’s modernization process. Just as Blair pulled the British Labour Party from its trade union roots toward a more liberal, moderate position in the mid-1990s, Rama has pulled his party to the center from its statist roots — though rechristened as the Socialist Party in 1991, the formerly communist party, in its iteration as the Albanian Labor Party, governed Albania as a one-party state from 1941 to 1991.

If elected, Rama is expected to pursue a moderate program of economic liberalization and further European integration.

But another more tactical reason for the Albanian left’s momentum is its alliance with another smaller, though important, leftist political party, the Lëvizja Socialiste për Integrim (LSI, Socialist Movement for Integration), a party founded by former Socialist prime minister Ilir Meta in 2004. Meta, who served as prime minister from 1999 to 2002, broke firmly with the mainstream Albanian left after the contested 2009 elections. Though his party won just four seats in 2009, Meta delivered those four votes to form a governing coalition with Berisha’s Democratic Party. Between 2009 and 2011, Meta served as deputy prime minister, minister for foreign affairs and minister for economy, trade and energy. Rama and Meta have since reconciled, however, and Rama is leading the most united leftist campaign in a decade.

The Democratic Party has traditionally been strongest in Albania’s north, while the Socialist Party has been strongest in its south. Those regional strongholds and a transition to a purely proportional representation system prior to the 2009 elections mean that you shouldn’t expect the Socialists to win a lopsided mandate.

Albanian GDP per capita — between just $7,000 and $8,000 — lags significantly far behind that of Romania and Bulgaria, currently the newest and least wealthy of the European Union’s members. That puts the Albanian economy on par with Ukraine or the chronically paralyzed Bosnia and Herzegovina, well behind even the other former Yugoslav states.