The economic blogosphere is lighting up over reports that Polish prime minister Donald Tusk is now talking about a referendum for his country to join the eurozone.![]()

That’s a big deal on the surface — with 40 million people, Poland is the largest European Union member after the United Kingdom not to use the single currency, and it’s one of eastern Europe’s fastest-growing economies.

Paul Krugman at The New York Times and Dylan Matthews at The Washington Post‘s Wonkblog are on the case, with very solid arguments for why Poland is crazy to want to join the eurozone. Writes Matthews:

It’s fair enough if Poland wants to develop closer ties to its European neighbors. But as [Krugman notes], joining the euro would deprive Poland of the strategy that allowed it to weather the recession so effectively. The key to the Polish miracle was massive currency devaluation.

Krugman and Matthews both highlight that the Polish key to outperforming the rest of Europe has been its ability to devalue the złoty and control its own monetary policy. It’s also helped that Poland has one of Europe’s lowest public debt loads — around 55% of GDP, compared to Germany’s 80% public debt load or 90% in France.

If you need to look any further for counterfactual proof, take a look at former East Germany, where economic growth still lacks former West Germany — despite the overwhelmingly strong political rationale for Germany reunification, it’s not clear that a currency union with West Germany made economic sense for East Germany, let alone a currency union with France, Belgium and the Netherlands. The Czech Republic, Slovakia and Poland have all grown at more rapid rates in the past two decades.

Krugman writes, ‘It really does make you want to bang your head against a wall.’

But they should probably calm down, because Poland is as unlikely as ever to join the eurozone — Tusk isn’t taking a gamble so much as he’s taking a bath on the Polish currency issue by pushing its resolution to sometime ‘at the end of the decade‘ — and far after the next Polish election.

Over two-thirds of Polish voters oppose eurozone membership, and those numbers seem unlikely to change anytime soon, given the chaos we’ve seen in peripheral eurozone countries from Cyprus to Portugal.

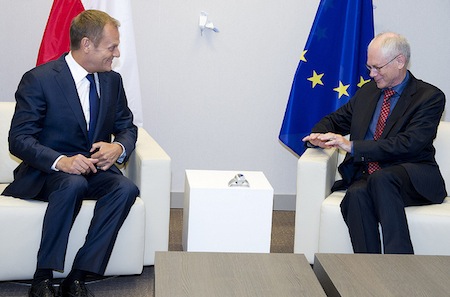

Tusk (pictured above with European Council president Herman van Rompuy), who has long been in favor of eurozone membership for Poland, is looking for a way out, not a way in. Facing reelection in 2015 for his liberal center-right Platforma Obywatelska (PO, Civic Platform), Tusk certainly doesn’t want to go to voters with the albatross of eurozone support around his neck.

Under the terms of their accession to the European Union in 2004, the eastern European members — including Poland — all agreed that they would eventually introduce the euro, and Tusk’s pro-euro stance come from that era when economic times were better and the fundamental flaws to the single currency weren’t as starkly on view as they are today.

Note that under the terms of past EU treaties, however, governments also agreed to keep their budgets to within 3% of GDP, and not even Germany abided that rule in the mid-2000s. Besides, nobody really believes that Brussels is willing to kick Poland out of the EU by a date certain if they refuse to adopt the euro. That’s especially true when other EU members like Sweden and the United Kingdom aren’t subject to the same binding obligation to join the euro — there’s little justification for having different rules for the British and the Polish.

Tusk’s chief political opponent, Prawo i Sprawiedliwość (PiS, Law and Justice), the socially conservative party led by former prime minister Jarosław Kaczyński, brother of late former president Lech Kaczyński, wholly opposes eurozone membership. A mid-March poll gives Civic Platform just a 29% to 23% lead over Law and Justice, and recent polls have shown a more narrow race — although it’s two years out, no one expects Civic Platform to waltz to victory seeking a third-consecutive term in office — it won just 39.2% in the 2011 elections, a falloff from the 41.5% it won in the 2007 elections.

If it will win the next election, Civic Platform will do so largely on the economic record that’s resulted from Polish currency and monetary autonomy.

While just as there were geopolitical reasons for German reunification, there are solid reasons for Poland to bind itself to the EU and to the North Atlantic Treaty Organization. But it’s not clear what further strategic gains Poland would make by joining the eurozone, especially given the loss of autonomy that would entail.

This is, after all, a country that in 2010 wildly celebrated the 700th anniversary of the Polish victory over Germanic troops in the Battle of Grunwald. After carving back its independence in 1918 over a century after the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth crumbled in 1795 as the Prussian empire rose, Poland found its independence subdued through much of the 20th century — first by Nazi Germany and then by Soviet Russia. So Poland, more than most countries, has a reason to jealously guard its new-found sovereignty, monetary or otherwise.

Eurozone membership would require a constitutional amendment, which in turn requires a two-thirds majority in the Sejm, the lower house of the Polish national assembly. Civic Platform currently holds just 206 of the 430 seats — just shy of an absolute majority, let alone a two-thirds supermajority. Tusk is hoping to trade a referendum for Civic Platform’s support in changing Article 227 of the Polish constitution, which mandates that only the National Bank of Poland may issue currency.