If you already thought that Venezuela was the Turkmenistan of Latin American politics, you need no further proof than the latest stunt on Tuesday from acting president Nicolás Maduro.![]()

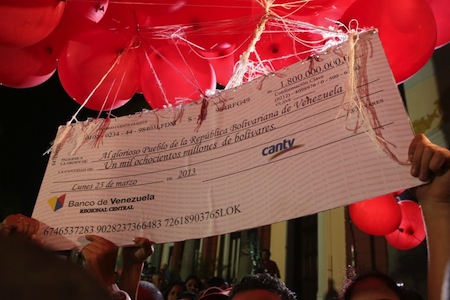

In the clip below, Maduro has launched an oversized check up to the heavens to a grateful Hugo Chávez, representing the dividends received by CANTV, the Venezuelan telephone company that Chávez nationalized in 2007. It’s another great find from Caracas Chronicles, which has been on quite a roll in the post-Chávez era in covering Venezuelan politics:

‘!Vuela, Vuela!, ¡en homenaje al Comandante!,’ Maduro exclaims (‘Fly! Fly! In tribute to the comandante!’), as red balloons (red symbolizing the color most associated with Chávez) float the check of 1,800 million bolívars upward to the skies.

As outrageous as it seems, it’s part of a series of impressions that the post-Chávez era is featuring an even creepier cult of personality in Venezuela than when el comandante was alive.

It began with the plans — now apparently aborted — to embalm Chávez and place him on display, just like Vladimir Lenin is on display in Moscow or Mao Zedong is on display in Beijing. Those plans were belatedly phased out after officials determined that officials had waited too long after Chávez’s death in order to embalm him.

Then there are the over-the-top tributes like this, mingling the legacy of Chávez with that of Venezuelan founding father Simón Bolívar and other left-wing martyrs, and even Chávez’s Cuban benefactors have a thorough celebration of his life at Granma.

Maduro even joked (or was it a serious claim?) that Chávez, his place in heaven secured, nudged God to make Argentine cardinal Jose Maria Bergoglio the world’s first Latin American pope.

It wouldn’t surprise me if, like in Turkmenistan, Maduro started trying to rename the months of the calendar after Chávez — there’s even a snarky website, madurodice.com, that tracks the number of Maduro’s mentions of Chávez on the campaign pre-campaign trail.

But the massive miles-long queues of people waiting to pay tribute to Chávez in death, and an extremely elegant funeral that drew nearly every leader in Latin America from Chile to México, with a ley seca (dry law) implemented to keep life in Caracas especially a bit more subdued in the potentially challenging days following Chávez’s death should have been enough to mark the extremely oversized impact that Chávez played within Venezuela’s political system — and above all in the spoils system that funneled oil wealth from the government to its supporters, from top government officials on downward.

All of this and Venezuela’s formal campaign season doesn’t even kick off until April 1.

French public intellectual Bernard Henri-Lévy has already decried the growing chavismo cult of personality:

What is less known, something that we will regret overlooking as the posthumous cult of Chávez swells and grows more toxic, is that this “21st-century socialist,” this supposedly tireless “defender of human rights,” ruled by muzzling the media, shutting down television stations that were critical of him, and denying the opposition access to the state news networks.

For Chávez supporters, there are certainly myriad policy reasons to support Maduro in the upcoming election over challenger Henrique Capriles — like him or not, he fundamentally transferred Venezuela’s oil wealth to the poorest Venezuelans in amounts unknown in nearly a century of the country’s oil wealth. You can argue that Chávez’s redistribution of wealth has been inefficient, that his expropriations and other economic policies have left Venezuela mired in debt, a pariah of the global financial system and ill-prepared for the day that oil prices drop, and that other more moderate regimes from Perú to Brazil have notched records of poverty reduction just as impressive as — or more so than — Venezuela under chavismo.

But in Venezuela, it’s indisputable that Chávez’s policies have directly lifted much of the previously poor out of poverty, with misiones (sustainable or not) that have provided nearly a decade and a half of funding for education and health care. Chávez’s supporters don’t give a fig about what’s happened in Perú or Brazil — they just know that Chávez has been their champion after a half-century of exclusion from political representation by the two major pre-Chávez parties of post-1985 democratic Venezuela, the Acción Democrática (AD, Democratic Action) and Comité de Organización Política Electoral Independiente (more well-known as COPEI or the Partido Popular, the Political Electoral Independent Organization Committee).

It’s true, however, that Chávez’s appeal has always been as much emotional as economic, his supporters feel a uniquely personal tie to Chávez, and that Maduro’s campaign rests almost exclusively on the fact that he is the hand-picked successor to Chávez. Maduro, as compared to Chávez today, falls short of the charisma his benefactor wielded and the trust that he commanded among a majority of the Venezuelan electorate for over a decade.

Nonetheless, Maduro seems to want to transform chavismo from a state ideology into something approaching a secular religion. That’s a dangerous game to play for the sake of a short-term gain — winning an election in three weeks’ time that, even without the wacky histrionics, most Capriles supporters expect Maduro to win at this point. It puts the Partido Socialista Unido de Venezuela (PSUV, or United Socialist Party of Venezuela) of Chávez and Maduro in a dicey long-term gamble.

By wrapping himself not only in the legacy of chavismo, but in the very ghost and godhead of Chávez himself, especially if Maduro fails to chart a course of madurismo (or whatever) for the next six years, he will have ensured, that Chávez and chavismo owns the next six years of Venezuelan policy as well. Maybe that’s rightly so, given that longtime energy minister Rafael Ramírez and finance minister Jorge Giordani, who have both steered Venezuelan economic policymaking over the past decade or longer, seem likely continue in their roles in any future Maduro administration. They made their bed, so to speak, let them lie in it, with or without Chávez and his political gifts around.

But if Maduro wins the April 14 election and Venezuelan finances take a turn for the worse — and that seems likely, given the recent bolívar devaluations, growing budget deficits, increasing reliance on Chinese debt and a drop in oil output over the past decade — Maduro has risked tarnishing the entire chavismo project with economic collapse, and that includes both the good and the bad of chavismo — and yes, there are positive aspects of chavismo as well as negative. Even more woe to Maduro and the legacy of chavismo if economic slowdown in China, India and the eurozone send oil prices tumbling.

If the past weeks are any indication, the campaign ahead stands to be waged on much different lines than most election campaigns, and even in different terms than the campaign for the previous October 2012 presidential campaign that pitted Chávez against Capriles.

An emotional campaign based on the cult of Chávez may win a full term for Maduro, but it’s a strategy not without its own risks in the years ahead.

One thought on “In death, the Chávez cult has become even creepier”