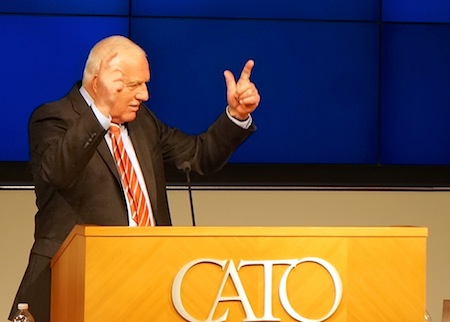

Just three days after leaving the Czech presidency, Václav Klaus spoke at the Cato Institute in Washington earlier today — Klaus is joining Cato as a senior distinguished fellow this spring.![]()

![]()

Klaus, who stepped down after a decade in office, didn’t break much new ground — his remarks were essentially everything you’d expect from the famously euroskpetic former president, who was the last European Union head of state to sign the Treaty of Lisbon (and quite reluctantly, at that).

The great eurozone fight

In brief, Klaus has long argued that the eurozone is not an optimal currency zone, it’s a project that was implemented without sufficient democratic input from everyday Europeans, and the economic costs of monetary integration and centralization far outweigh the benefits, and those costs have become increasingly evident from the economic pain suffered today in Greece, Spain, Italy and throughout Europe.

Klaus’s diagnosis has become fairly uncontroversial — both on the left and the right, and for both intergovernmentalists and neo-functionalists alike. A lot of European federalists would agree that the European Union needs more robust democratic institutions at the supranational level. Many economists agree that the one-size-fits-all monetary policy has been incredibly harmful to many countries in southern Europe since 2008, and the painful internal devaluation forced upon many countries in the European periphery, from Latvia to Greece, has been a needless exercise in poor economic policymaking.

But whereas many economists would argue that the solution lies in greater fiscal harmony (especially through fiscal transfers from wealthier regions to poorer regions), looser monetary policy, a eurozone-wide borrowing capacity, debt forgiveness and a doubling-down on the more long-standing commitment to the free movement of goods, services and people throughout the European Union, Klaus’s solution is to unwind the eurozone.

Klaus would rather see a way for Greece — and other troubled economies — to simply exit from a eurozone that’s delivered now nearly half a decade of GDP contraction, painful downward pressure on income, and widespread unemployment and social rupture.

That’s not a crazy idea economically — if Greece could leave the eurozone tomorrow (or if Greece simply went bankrupt, thereby essentially forcing Greece out of the eurozone), it could conceivably pursue a much more aggressive monetary policy, devalue its currency, and take other steps to make its exports more competitive in global markets once it’s no longer yoked to a monetary policy that’s better suited for, say, the German economy.

But that’s not the entire story. Greece might also suffer extraordinarily in the short-run while it makes that transition — starting with how it would reintroduce the drachma and how it would even finance basic governance outside the current eurozone regime, forcing perhaps even more austere budget-cutting in a country where the social safety net is already tattered.

And those are just the problems inside Greece — though the Greek economy is just a fraction of the European economy, it could set off a chain reaction of fear, bank runs and deep recession throughout the eurozone as investors pull out of not only the peripheral economies, but also out of the entire eurozone. How would a massive Greek devaluation affect Cyprus? Would Spain and Italy withstand the inevitable bank runs and currency flight? The chain reaction of unraveling one of the world’s foremost reserve currencies could well be catastrophic.

Looking to national parallels: the Czechoslovak breakup and German reunification

Klaus related the current monetary union to the breakup 20 years ago of Czechoslovakia into two separate nations — a process that Klaus said was painful though necessary (though the Slovak economy is doing much better these days than the Czech economy). But Greeks might be troubled by the more painful example of the breakup of the Yugoslav federation and the Soviet Union, both of which were also monetary unions as well as political unions. The breakup of the ‘ruble zone’ led to massive hyperinflation throughout the Soviet Union and an economic shock that cut standard of living in half. There’s simply no way to know what forces could be unleashed by the process — no matter what anyone says, there’s not a precedent for unraveling even a tiny part of the world’s largest currency union in an orderly fashion.

I would have liked to hear, in particular, Klaus’s thoughts on another contemporary experiment in currency union: German reunification.

In Germany and throughout Europe (despite UK prime minister Margaret Thatcher’s dark fears), the 1990 reunification is thought to have been a fantastic political success. But the economic data suggest it’s not been a particularly great deal economically for either side — the West German, and then simply German, government borrowed and spent billions on integrating East Germany into the newly federalized Germany. That hasn’t necessarily translated into higher growth for what used to be East Germany — while German GDP per capita, as a whole, is around $39,000, East German GDP per capita is much lower.

Taken as a region, former East Germany’s GDP per capita is around 70% of that in the former West, making it not much better off than its eastern European neighbors Poland (around $22,000) or the Czech Republic (around $27,000), both of which have seen some of the fastest GDP growth in the past decade, in contrast to the former East Germany. The Solidarity Pact, which has provided billions in subsidies to the former East, is set to run through 2019, though the former East is likely to require additional subsidies to remain afloat well after 2019.

On Klaus’s view, economic considerations provide a strong argument that East Germany should never have reintegrated with Germany — it might have been better off, like Poland and the Czech Republic, as a sovereign nation with the ability to pursue an independent monetary policy and establish a more accommodating currency.

I doubt he’d agree with that — largely for all of the political, cultural and emotional benefits that East Germans received from reuniting with their West German brothers and sisters — which is to make the parallel argument that there are additional political and cultural benefits that all Europeans receive from a currency union. Klaus might argue that those benefits are far higher in the ‘German union’ example than in the ‘European union’ example, but they nonetheless exist in the European context as well.

Looking toward the future of euroskepticism

For over a decade, Klaus has been Europe’s chief iconoclast, and there’s no denying he’s made certain that his voice is heard– and his perspective has been an important one at the negotiating table, not just most recently at Lisbon, but all the way back to Maastricht in 1992, when Klaus was the Czechoslovakian finance minister hopeful that his country would make the transition from a former Soviet satellite into, as Klaus said today, a ‘normal’ European state.

It seems increasingly plausible that an EU or even a eurozone country could one day elect a euroskpetical government — maybe not today, maybe not tomorrow, but eventually. That seems especially likely if European-level governing mechanisms can’t effectively pull the eurozone out of its current malaise. It might happen even if the eurozone survives, perhaps due to a more cohesive fiscal policy at the expense of national sovereignty.

Ultimately, Klaus was never willing to provoke a Czech — and European — constitutional crisis. He ultimately signed the Lisbon Treaty.

But it’s not clear that the next generation of euroskeptics will be so accommodating — even this week, disaffected Christian Democrats in Germany are forming a new anti-euro party. In the Netherlands, a budget-cutting government elected just last September is already unpopular — polls show that Geert Wilders’s anti-Islam Partij voor de Vrijheid (PVV, Party for Freedom), with a newfound populist disgust for the euro, is once again on the rise, in some cases winning more support than any other party.

What happens if Beppe Grillo’s anti-euro Movimento 5 Stelle (Five Star Movement) actually forms a government in Italy one day? What if a future Greek prime minister Alexis Tspiras, in trying to negotiate better Greek bailout terms, bluffs his country’s way out of the eurozone? What if Nigel Farage, the leader of the surging anti-Europe United Kingdom Independence Party, becomes the next deputy prime minister in a much more euroskpetic Tory-led government after 2015? What happens if Hungarian prime minister Viktor Orbán decides to rupture his country fully from the democratic norms that the European Union was formed in large part to nurture and foster?

Mainstream European leaders may be delighted that Klaus is no longer heading a European nation of 10.5 million people, but they may one day come to miss him, given the current euroskeptics at the gate. It’s all the more so true give that Klaus’s critics and supporters both agree that the eurozone’s future is far from secure.

Photo credit to Kevin Lees — Cato Institute, Washington DC, March 2013.