For what it’s worth, we have the final results from the weekend’s Italian election from the interior ministry.![]()

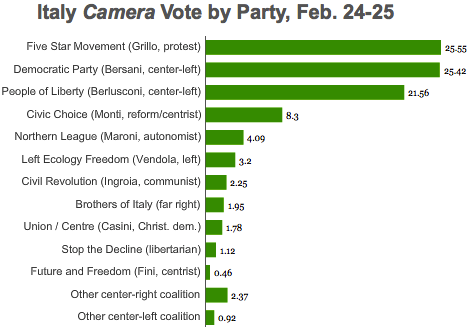

As exit polls indicated and early resulted showed, Pier Luigi Bersani’s centrosinistra (center-left) coalition won 29.54% in the race for Italy’s lower house of parliament, the Camera dei Deputati (House of Deputies) to just 29.18% for former prime minister Silvio Berlusconi’s centrodestra (center-right) coalition, 25.55% for Beppe Grillo’s protest Movimento 5 Stelle (M5S, the Five Star Movement) and just 10.56% for technocratic prime minister Mario Monti’s centrist coalition.

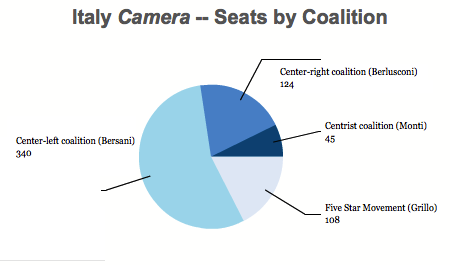

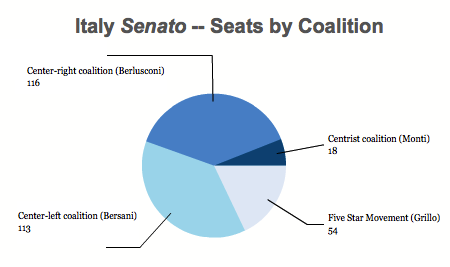

As the winner of the largest vote share, Bersani’s coalition is entitled to a majority of 54% of the seats in the lower house:

In the upper house, the Senato (Senate), there’s no such ‘seat bonus’ at the national level; instead, the winner in each of Italy’s 20 regions gets a ‘bonus’ in that it wins 55% of the seats in each region, meaning that the centrodestra actually edged out the centrosinistra in total number of senatorial seats, even though Bersani’s coalition won 31.42% and Berlusconi’s coalition won just 30.58%. That means, of course, if the Senato‘s seats were awarded on the same basis as the Camera‘s seats (they cannot be out of constitutional considerations with respect to Italy’s regions), Bersani would be the clear prime minister today.

The reason for the center-right’s senatorial victory is pretty clear when you look at the region-by-region winners (as shown the map below, with blue for centrodestra and red for centrosinistra):

As you can see, not only did Berlusconi nearly sweep the mezzogiorno, the swath of southern Italy that contains Campania and Sicily, (the second- and fourth-largest regions), his coalition won Lombardy, the largest prize in the center-north of the country. His coalition also came very close to winning Piedmont in the northeast and Lazio in the center as well, and the centrosinistra leads in total votes only because it was able to rack up large margins in its historically reliable heartland in the regions of Tuscany and Emilia-Romagna.

It’s in particular fascinating to take a look at the party-level vote, especially in the lower house elections, because you get a better sense of how the coalition system and the national ‘seat bonus’ system really has skewed the next parliament to favor the centrosinistra (center-left) coalition, despite the fact that Grillo’s Five Star Movement actually outpolled not only Berlusconi’s party, the Popolo della Libertà (PdL, People of Freedom), but also even Bersani’s party, the Partito Democratico (PD, Democratic Party), though it didn’t outpoll the broader center-left and center-right coalitions:

Here, however, is the breakdown of seats by party:

The disparity between vote share and awarded deputies shows how important coalitions have become in Italian elections since Berlusconi’s government changed Italy’s election law in 2005, which transformed the previous system — in operation from the early 1990s — a split vote that awarded most of the seats on a ‘first-past-the-post’ basis and some on a proportional representation basis to the current ‘proportional representation’ system (with a national ‘bonus’ in the lower house and a regional ‘bonus’ in the upper house).*

There’s a complicated regional system of proportional representation throughout 26 separate ‘electoral districts’ — in each district, there’s a 4% threshold for parties to win seats outside of a coalition and a 2% threshold for parties within a coalition.

The bottom line is that Monday’s results bear out just how beneficial it is to be part of a coalition — and, especially, the winning coalition.

So despite winning just 3.20% of the national vote, not enough to win a single seat outside of a coalition, Nichi Vendola’s leftist Sinistra Ecologia Libertà (SEL, Left Ecology Freedom) now claims 37 seats in the lower house.

The same is true for two very small allies within Bersani’s coalition:

- The Centro Democratico (Democratic Center), an alliance of small centist parties led by former Lombardy regional president Bruno Tabacco and former Rome mayor Francesco Rutelli, which won six seats, though just 0.49% of the national vote.

- The regional Partito Popolare Sudtirolese (South Tyrolean People’s Party) near the Swiss border won five seats, despite its 0.43% national support.

You can see how it’s true for even losing coalitions — the Unione di Centro (UdC, Union of the Centre), despite winning just 1.78% of the vote nationally, will nonetheless hold onto eight deputies (lower than its 36 deputies in the previous parliament).

On the flip side, parties such as Italia dei Valori (Italy of Values), the longtime anti-corruption party of magistrate-turned-politician Antonio Di Pietro, which was part of the centrosinistra coalition in 2009, will have lost all 29 of its deputies by joining up with the more far-left Rivoluzione Civile (Civil Revolution) coalition, which won, in total, just 2.25% of the vote.

Indeed, the Partito della Rifondazione Comunista (PRC, Party of the Communist Refoundation) has now been shut out of Italy’s parliament in two consecutive elections — it was part of former prime minister Romano Prodi’s broad coalition in the 2006 elections, when it won 41 seats and enough clout with Prodi to demand that its leader, Fausto Bertinotti, become the president of the lower house.

Election law reform, therefore, may well be one of the few items on the agenda for the next parliament in advance of a new set of elections, though it remains to be seen what a new election law would include. Berlusconi is likely still keen on retaining the law he pushed through in 2005, Bersani knows he owes his disproportionately outsized majority in the lower house to the current election law (though he might like to revise the law to make senatorial elections a little easier for the center-left), and the party that could stand most to gain from a return to the first-past-the-post system, the regional autonomist party, Lega Nord (Northern League), has gone from 60 deputies in the last parliament to just 18.

The major party/movement leaders continued to stake out ground throughout Tuesday, however, largely suggesting some of the four options I outlined yesterday:

Bersani, in his first major comments since the election, struck a note of humility, rightly stating that although his coalition placed first, it didn’t win. He seemed to rule out any alliances, especially a ‘grand alliance’ with Berlusconi, in particular, though seemed open to an informal senatorial alliance with Grillo’s Five Star Movement — and indeed, Bersani argued that the election results showed that austerity alone wasn’t a sufficient program for governing.

Berlusconi has hinted today that he favors a ‘grand coalition’ with Bersani and, although the PdL and the PD banded together after Berlusconi’s government resigned in November 2011 to support Monti’s technocratic government, Berlusconi precipitated slightly earlier elections by pulling his party’s support for Monti and thereafter, running against Monti in the campaign leading up to the weekend’s vote.

Grillo himself seemed more open Wednesday to an informal, if temporary, alliance with Bersani’s coalition, and Open Europe notes that the body language of both Bersani and Grillo seems to indicate that they are edging closer to that possibility — I argued yesterday that we already have a blueprint for an informal alliance between the center-left and the Five Star Movement in the Sicilian regional parliament, and that a Bersani-Grillo alliance might unite the Italian left in ways that a Bersani-Monti alliance would have destabilized the left.

In other news, Italians turned Wednesday to the vote-counting in regional elections in Lombardy, Lazio and Molise.

* UC-Davis professor of political science Matthew Shugart rightly notes that we don’t have a tidy name for this kind of electoral system, also used during Greek elections, which really is a mix of proportional representation and majoritarian elements.

2 thoughts on “More thoughts on the final Italian election results and Italy’s electoral law”