This is the seventh and final post in a series examining the Chinese leaders named to the Politburo Standing Committee during the 18th National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party (中国共产党) that concluded November 14. Prior installments on Zhang Gaoli here, Zhang Dejiang here, Liu Yunshan here, Yu Zhengsheng here, Wang Qishan here and likely future premier Li Keqiang here.

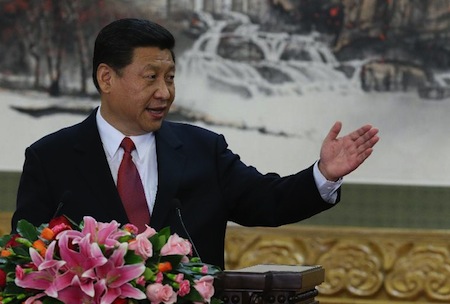

In many ways, there’s not much I can add to what the world’s press has already written about Xi Jinping (习近平) in the past 24 hours, who’s been the newest figure on the world scene since becoming the general secretary of the Party yesterday and, in a bit of a surprise, also the chairman of the Party’s Central Military Commission. He is expected to take over before March 2013 as China’s president, thereby fully succeeding Hu Jintao (胡锦涛).![]()

There’s much we already know about Xi — starting with the fact that much of the world’s press and other policymakers find Xi leagues more expressive and relatable than Hu.

Xi is a ‘princeling’ — the son of Xi Zhongxun, a revolutionary hero, former vice premier and Politburo member, who was purged during the Cultural Revolution, but returned to help Deng Xiaoping in the 1980s to develop parts of Guangdong provide as special economic zones. When Xi Zhongxun was purged from the leadership in the 1960s, however, and Xi Jinping was just 15 years old, he was sent off to a remote village in Shaanxi province in the center of China.

As Robert Lawrence Kuhn writes in How China’s Leaders Think, Xi Jinping’s time in the ‘wilderness,’ so to speak, has now become part of his mythology:

Xi Jinping spent the next six years in this harsh, poor rural area — chopping hay, reaping wheat and herding sheep as a member of a local work unit. He lived in a cave house, as was the local custom. But he adjusted well to his new life, impressing older colleagues with his enthusiasm to labor long and hard, and with his personal modesty. He built a reputation for endurance by winning wrestling matches with farmers, and by carrying ‘a shoulder pole of twin 110-pound buckets of wheat for several miles across mountain paths without showing fatigue.’

Xi did not lose his love of studying, however: by night, he would read thick books in the dim light of kerosene lamps. The locals liked to go to his cave to listen to his stories about history and the world beyond the mountains. Everyone, old and young, enjoyed chatting with him.

I’m not sure whether this is just so much hagiography for the next ‘paramount leader’ of the world’s largest country, but there’s no doubt that the young Xi certainly made an impression, and Xi was soon off to Beijing’s prestigious Tsinghua University, where he studied engineering. Xi also holds a doctorate in law.

He spent much of his early career in Fujian, a province of nearly 37 million people on the Chinese coast just north of Guangdong province.

In 2002, Xi became the Party secretary of Zhejiang province, the province that lies immediately south of Shanghai, is home to 54 million people and is generally one of China’s most prosperous provinces, with double-digit growth rates during much of Xi’s tenure. Kuhn reports that Xi was untainted by allegations of corruption and, indeed, had ‘zero tolerance’ for corruption and dishonesty — a fact that bodes well at a time when the Party’s been struck with corruption scandals that touch everyone from outgoing premier Wen Jiabao to the disgraced former Party secretary of Chongqing municipality, Bo Xilai.

Although Xi was appointed Party secretary of Shanghai municipality in 2007, he was appointed in the same year to the Politburo Standing Committee, and he quickly left the Shanghai position to assume the PRC vice presidency where, among other duties, he was responsible for overseeing the 2008 Summer Olympics in Beijing.

Notably, his wife is Peng Liyuan, who until very recently was more well-known in China than Xi. Peng is a popular singer and entertainer with the People’s Liberation Army (she’s technically a major general). Perhaps even more interesting, however, is that Xi’s first wife, Ke Lingling is the daughter of a former Chinese ambassador to the United Kingdom, and Ke still lives there today (and not in China).

But there’s also much we don’t know about Xi, notably in the way he hopes to lead the People’s Republic of China over the next decade.

Beyond vague platitudes, first and foremost about continuing China’s economic reforms and GDP growth, we don’t really know whether Xi will be more open to political reform and greater political participation than outgoing Chinese leader Hu Jintao.

Cheng Li, director of research and a senior fellow at the John L. Thornton China Center, ventures the following analysis in his profile on Xi:

Xi has long been known for his market-friendly approach to economic development. Yet he has also displayed strong support for “big companies,” especially China’s flagship state-owned enterprises, which monopolize many major industrial sectors in the country. Xi’s experience in the military—serving as a personal assistant to the minister of defence early in his career—also makes him stand out among his peers. Xi’s views concerning China’s political reforms appear to be remarkably conservative, seemingly in ling with old-fashioned Marxist doctrines.

In many ways, the Congress that just ended had more to do with a showdown between former leader Jiang Zemin (江泽民) — thought to be dying a year ago, he has emerged as a key power broker during the current transition — and outgoing leader Hu Jintao than it did with Xi and China’s future leadership.

But although many of the five new members of the Politburo Standing Committee have ties to Jiang, none of them will be eligible for reappointment at the next expected congress in 2017, which means Xi and likely premier Li Keqiang (李克强) may well make the decision as to who among the next generation will accede to the leadership as the ‘sixth generation’ in 2022.

In the meanwhile, Xi, Li and the entire Chinese leadership will have an extraordinary amount of issues to face, from diplomatic crises with Japan to China’s economy and the emergence of a trillion-strong middle class. For now, however, although the transition continues through the People’s National Congress, expected to begin next March, Xi has most certainly arrived as the world’s newest power broker.

3 thoughts on “Fifth Generation: Who is Xi Jinping?”