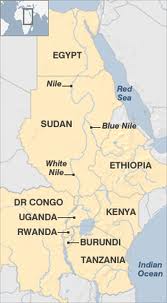

Though you might think of the Nile as a primarily Egyptian river in Africa, its roots go much deeper. The White Nile originates far within sub-Saharan Africa at Lake Victoria, winding up through Juba, the capital of the newly-minted country of South Sudan, and the Blue Nile originates at Lake Tana in northeastern Ethiopia, and it joins the While Nile near Khartoum, the capital of (north) Sudan. ![]()

![]()

But the rights to the water originating from the Blue Nile have become the subject of an increasingly tense showdown between Egypt and Ethiopia, with Ethiopia moving forward to bring its long-planned Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam into operating, sparking a diplomatic showdown between the two countries and a crisis between two relatively new leaders, both of whom took office in summer 2012 — Ethiopian prime minister Hailemariam Desalegn and Egyptian president Mohammed Morsi.

The Renaissance Dam and the politics of the Nile were no less fraught between former Egyptian president Hosni Mubarak and the late Ethiopian prime minister Meles Zenawi. But with the project moving forward, Hailemariam and Morsi are locked in a diplomatic tussle that could escalate into something much worse. Morsi has recently warned Ethiopia that ‘all options are open,’ which conceivably includes an Egyptian air attack to bomb the Renaissance Dam, which would initiate military confrontation between the second-most and third-most populous countries on the continent of Africa.

The Renaissance Dam is Meles’s legacy project and, with a price tag of between $4 billion and $5 billion, it’s embedded with an atypical amount of Ethiopian national pride. When it is completed, the dam will make Ethiopia a huge hydroelectric producer, perhaps Africa’s largest energy producer, with an estimated generation of 6,000 megawatts of electricity. To put that in perspective, the Hoover Dam in the southwestern United States has a maximum generation of around 2,100 megawatts and Egypt’s own Aswan High Dam has a maximum of around 2,500 megawatta, while China’s Three Gorges Dam has a maximum capacity of 22,500 megawatts.

Egypt’s chief concern is that the dam will reduce the amount of water that currently flows from the Blue Nile to the Nile Delta, and Ethiopia has already started to divert the course of the Blue Nile to start filling the Renaissance Dam’s reservoir (see below a map of the Nile and its tributaries). While that process is expected to temporarily reduce the amount of water that flows to Sudan and to Egypt for up to three years, Egyptian officials have voiced concerns that the Renaissance Dam might permanently reduce the flow of the Nile through Egypt, despite technical reassurances to the contrary. Moreover, Egyptian officials point to colonial-era treaties with the United Kingdom from 1929 and 1959 that purported to divide the Nile’s riparian rights solely as between Egypt and the Sudan, without regard for Ethiopian, Ugandan, Tanzanian or other upriver national claims. Ethiopian anger at exclusion from the 1959 Nile basin negotiations led, in part, to the decision by Ethiopian emperor Haile Selassie I to claim the independence of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church from the Coptic Orthodox Church based in Alexandria, Egypt.

It’s clear however, where Ethiopia’s Nile neighbors stand on the issue — the leaders of South Sudan and Uganda have voiced their approval for the project, and even Sudan, which will also mark some reduction in Nile water while the dam is constructed, is inclined to support it, which will result in a wider source of crucial electricity throughout the Horn of Africa, east Africa and beyond. Ironically, it could even be Sudanese president Omar al-Bashir, currently under indictment by the International Criminal Court for atrocities stemming from the Darfur humanitarian crisis in the mid-2000s, who has the regional credibility with both Cairo and Addis Ababa to diffuse the crisis. Continue reading Will Egypt and Ethiopia come to blows over the Renaissance Dam and water politics?