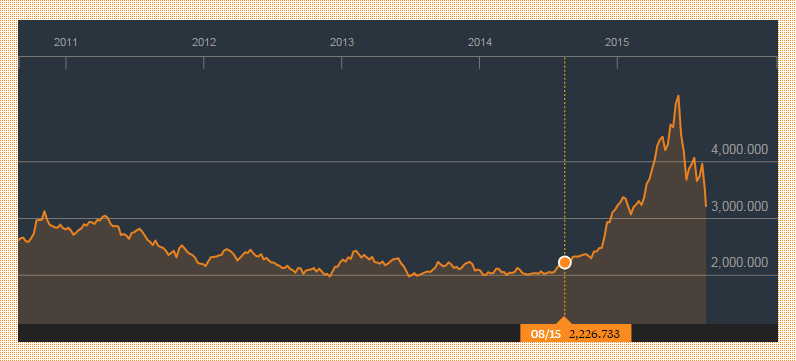

In January 2014, the Shanghai Composite Index was hovering at around 2,000.

Today, it’s ‘down’ to just above 3,600 and everyone from Beijing to London is gnashing teeth and wrenching hands over the great Chinese stock market crash of 2015.

However, in the light of the massive gains of the past two years, the current bear market seems more like a correction than a crash. You wouldn’t know it, though, from the response of China’s one-party state, which has intervened in just about every way imaginable to prop up the equities market.

Part of the anxiety, both in China and abroad, is due to the country’s role in the global economy — as the era of double-digit annual growth slows to ‘just’ 6% or 7% growth, global demand from the world’s largest economy will invariably slow. That will have a global impact. But no one expected China to grow at spectacularly outsized rates for decades without end, and that alone isn’t necessarily enough to torpedo the US or European economies. The ups and downs of China’s wild stock markets, moreover, aren’t necessarily correlated with long-term economic growth. That doesn’t obviate some of the real harms suffered by largely unsophisticated retail investors who dumped their savings into Chinese stocks during the rally of the past year and a half.

This underlines that the real crisis is political, not economic. Under pressure to ‘do something,’ the Chinese Communist Party (中国共产党) is doing a little of everything — devaluing the yuan, halting new IPOs, prohibiting trading in some of the hardest-hit stocks, buying stock in an attempt to keep prices artificially high, cutting interest rates. Certain institutional investors will not be permitted to trade (i.e. sell) stocks for up to six months.

It’s a panicky response that only further perpetuates the ‘crash’ narrative and further sell-offs. But it’s also the response of a governing regime that knows — and knows that the Chinese people know — there’s no competing political party to blame. Chinese leaders often argue that the one-party system incentivizes long-term policy planning because there’s no short-term gains to be had from elections every two years. But the acute knowledge that the Communist Party owns every policy (and every policy misstep) cuts both ways. The current stock market turbulence shows that Chinese Communists, just like American Republicans or Democrats, aren’t above taking hasty steps to end short-term political pain. Continue reading China’s stock market crash is a political, not economic, crisis →

![]()