When you walk through the streets of New York or Washington or even Houston or Los Angeles today, the air is clear — by at least global standards.![]()

![]()

That’s due, in part to the 1963 Clean Air Act in the United States, which together with wide-ranging 1970 and 1990 amendments that have largely brought air pollution under control within the United States. Sure, Los Angeles is still known for its smog, but the worst day in Los Angeles is barely a typical day in Beijing.

The PM2.5 reading (a measurement of particulates in the air) for Los Angeles last year averaged around 18. In Beijing? A PM2.5 reading of 90, on average. Los Angeles’s worst day was 79, while Beijing’s was 569.

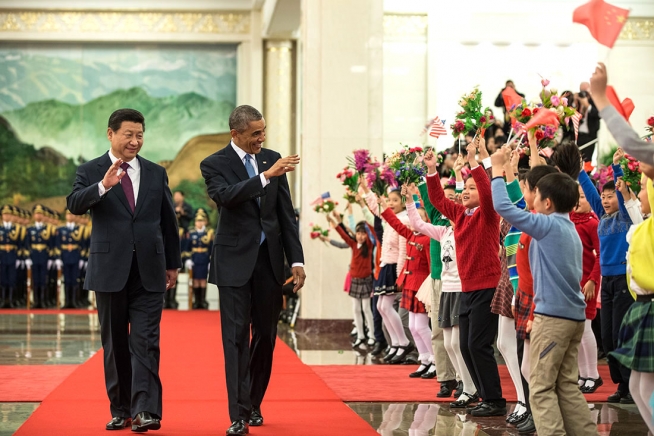

That’s one of the reasons that the landmark carbon emissions agreement between the United States and the People’s Republic of China, announced in the wake of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) summit is such a big deal — it’s not necessarily a coup for US diplomacy, but it’s definitely a signal that Chinese authorities are taking pollution seriously. It shows that Chinese leaders under president leader Xi Jinping (习近平) recognize that in order to showcase their seriousness about environmental hazards, they have to engage the international community on climate change.

Landmark though the US-Chinese bilateral agreement may be, it is still much more about domestic Chinese priorities than trans-Pacific good will. As James Fallows writes in The Atlantic, pollution and environmental harms are the single-most existential challenge to the now 65-year rule of the Chinese Communist Party (中国共产党):

But when children are developing lung cancer, when people in the capital city are on average dying five years too early because of air pollution, when water and agricultural soil and food supplies are increasingly poisoned, a system just won’t last. The Chinese Communist Party itself has recognized this, in shifting in the past three years from pollution denialism to a “we’re on your side to clean things up!” official stance.

If you want to showcase to 1.35 million citizens that you’re serious about the environment, there’s no better way than signing a high-profile agreement with the world’s largest economy (and the world’s second-largest carbon emitter).

Xi himself has admitted earlier this year that it’s China’s most vexing policy issue, when he plainly stated that pollution is Beijing’s most pressing problem. Shortly thereafter, in March, premier Li Keqiang (李克强) declared a ‘war on pollution’ within China:

“Smog is affecting larger parts of China, and environmental pollution has become a major problem,” Mr. Li said, “which is nature’s red-light warning against the model of inefficient and blind development.”

That’s already having an effect, with the first drop in coal use in China in over a century, a result that’s possibly affecting global coal prices, though part of the effect might be explained by a slowing Chinese economy — it’s expected to grow at a pace of just 7.5% this year. That’s still robust by most standards, but it would be the lowest reported GDP growth in China since 1990.

Republicans in the United States grumbled that the pact was ‘one-sided,’ and perhaps it was (though you’d expect grumbling from incoming US Senate majority leader Mitch McConnell, a Republican from Kentucky, the heart of the US coal mining industry). But if so, it’s one-sided in the way that unilaterally lowering tariffs is good for trade. But US president Barack Obama’s commitment to lower US carbon emissions by 2025 by between 26% and 28% (compared to 2005 levels) is only going to accelerate the transition of the US economy from fossil fuels to cheaper, cleaner alternatives, including renewable energy.

China, on the other hand, has agreed to reduced emissions that it expects to peak in the year 2030, when it hopes to raise 20% of its energy from zero-carbon emission sources under the agreement. But Obama has already, through executive action, committed the US Environmental Protection Agency to work to reduce emissions levels by 17% through the year 2020, so the United States (for now) is already committed to carbon reductions on a unilateral basis.

Of course that’s lopsided, to some degree, but only if you ignore that the United States and Europe polluted without abandon in the 18th and 19th centuries when they were going through the same level of industrialization and development — and they surely didn’t do it with national populations of over a billion consumers.

Today, China is by far the largest emitter of carbon into the global atmosphere, responsible for 29% of the world’s total carbon emissions, while the United States is responsible for 15%, the European Union 10%, India 7.1% and Russia another 5.3%. As White House correspondent Josh Lederman writes for the Associated Press, however, one of the agreement’s benefits might be in the power it will have to nudge other countries to join the fight against carbon emissions and its role in climate change with the 2015 Paris conference fast approaching:

Scientists have pointed to the budding climate treaty, intended to be finalized next year in Paris, as a final opportunity to get emissions in check before the worst effects of climate change become unavoidable. The goal is for each nation to pledge to cut emissions by a specific amount, although negotiators are still haggling over whether those contributions should be binding. Developing nations like India and China have long balked at being on the hook for climate change as much as wealthy nations like the U.S. that have been polluting for much longer. But China analysts said Beijing’s willingness to cap its future emissions and to put Xi front and center signaled a significant turnaround.

But there’s an even stronger benefit in the US-Chinese accord, insofar as it demonstrates that Xi is willing to work with the United States on tricky issues, even as China scrambles to compete with the more developed US efforts (through the Trans-Pacific Partnership) to form an Asia/Pacific trade bloc.

As Chinese military and political influence grows throughout the Asia/Pacific region, agreements like today’s on carbon emissions show that US and Chinese diplomats are establishing strong working relationship for potential collaboration in the future — cooperation that could be vital in the decades to come in maintaining a peaceful Asia and world.