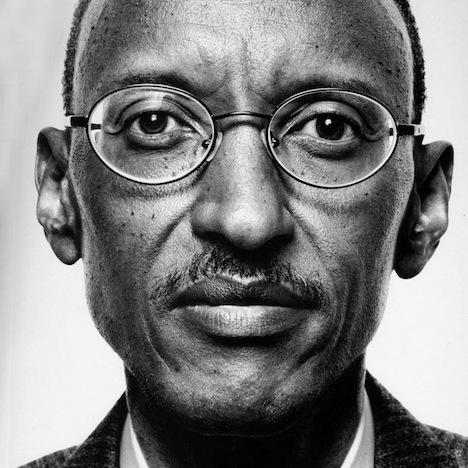

Rwandan president Paul Kagame’s Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) overwhelmingly won last week’s elections with a staggering 76% of the vote.![]()

That’s not surprising, given that Kagame’s been so intent on keeping any real opposition from gaining any real power.

One opposition party, the Green Party, won official recognition as a political party only earlier this summer, and its deputy in Rwanda’s parliament was murdered before prior 2010 elections — it’s hard not to conclude that it was intimidated from running this time around. Another opposition party, the FDU-Inkingi, was not permitted to run in the elections, and its leader Victoire Ingabire sits in prison on politically motivated charges.

Even in a world where sub-Saharan African democracy is growing stronger, Rwanda’s result is disappointing. The most you could take away from Rwanda’s elections are that they are somehow building the norm of regularized elections. In most sub-Saharan African countries, we’d call Kagame what he is — an anti-democratic strongman. His party, which springs out of the rebel military force that spent much of the early 1990s fighting against Rwanda’s central government and that took power in 1994, will control the lion’s share of the 80 seats in the unicameral Chamber of Deputies.

All signs point to his genuine popularity, however, and it’s hard to argue with an average GDP growth rate of over 8% since he formally became Rwanda’s president in 2000. In economic terms, Kagame’s delivered the best results of perhaps any African leader in the past decade — and he’s done it without oil or other mineral wealth.

But as I wrote before Rwanda’s elections, for all of the success Kagame has made in pacifying Rwanda (after all, we are only 19 years removed from the devastating genocide that took 800,000 lives in three months) and for building its economic infrastructure, there’s a nagging sense that all of Kagame’s progress could unwind if he leaves office without having built a political infrastructure as well:

But Kagame’s third task is perhaps the most important of all — crafting a political system that will guarantee and institutionalize the gains that Rwanda has made in the past two decades under Kagame. Kagame himself is term-limited to just two seven-terms in office as president, which means that, barring constitutional amendments, he will step down in 2017 — that’s just four years away. So we’re now entering a crucial time for Rwanda and for Kagame. And next month’s elections are the sole opportunity for electoral participation between now and 2017.

It’s easy enough to understand why Kagame fears the role of a truly free media or political parties, because both supposedly benign institutions played a major role in amplifying the Hutu interahamwe militias in the early 1990s that carried out most of the 1994 genocide. All too often, Western good-government types don’t understand how the liberalization of Rwanda’s political sphere and open radio airwaves accelerated the genocide.

Even if you accept that Kagame’s restrictions on freedom are acceptable in light of Rwanda’s very unique experience, or that a little authoritarianism goes a long way in stabilizing an economy (think of Kagame as a kind of 21st century, central African Park Chung-hee), you can still doubt whether Kagame is doing enough to build a formal political structure for Rwanda. Even in non-democratic countries like the People’s Republic of China, a (surprisingly responsive) political system still exists to tend to policymaking, provide stability, deal with issues of succession, and the like.

Though it’s now a faux pas in Rwanda to make reference to ‘Hutu’ or ‘Tutsi,’ the fact remains that the RPF is a chiefly Tutsi force that liberated Rwanda from the grip of a largely Hutu-based wave of terror. While Kagame’s administration has worked to approach justice very gently through the use of gacaca community-based trials, the absence of many high-level Hutus in government risks putting Rwanda in the same position that it was throughout the colonial era — a largely Tutsi elite and an increasingly resentful Hutu mass. Today, Kagame remains popular with a wide swath of all Rwandans, but that could one day change. Or a successor to Kagame could not be as fortunate in office. What may work today for Rwanda may work only because of the legitimate role Kagame played in healing such a broken nation. That’s why it’s even more important for Kagame to build a lasting, broad-based political system for his country, even if it’s an artificially choreographed system designed to keep both Hutu and Tutsis committed to stability — think of Lebanon’s stage-managed democratic system, for instance.

All of which makes last week’s parliamentary elections a missed opportunity to build whatever follows the Kagame era.