The results have been announced from Sunday‘s Cambodian parliamentary election and, not surprisingly, they are controversial.![]()

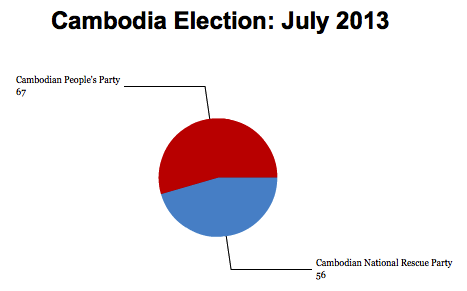

The official result is that the governing Cambodian People’s Party (CPP, គណបក្សប្រជាជនកម្ពុជា) of prime minister Hun Sen, who has held power in the landlocked southeastern Asian country of nearly 15 million since 1985 in one form or another, won 49.36% of the vote and 67 of the seats in the 123-member Rotsaphea, or National Assembly (រដ្ឋសភាជាតិ). The opposition Cambodian National Rescue Party (CNRP, គណបក្សសង្រ្គោះជាតិ), led by Sam Rainsy, who returned to Cambodia days ago to lead the campaign, won 44.34% of the vote and 56 seats.

Rainsy and the opposition have rejected the result, alleging fraud from the government of Hun Sen (pictured above):

Polling day was also plagued by allegations of cheating. Indelible ink, which is designed to prevent people from voting more than once, washed off easily. Names were left off voter lists and there were unsubstantiated claims that Vietnamese were being brought in from across the border to vote for the CPP.

The Vietnamese issue, in particular, is murky. Vietnamese migrants comprise nearly 5% of Cambodia’s population, and the CPP has made it relatively easy for Vietnamese migrants to come to Cambodia, where the Vietnamese overwhelmingly support the CPP and Hun Sen’s government, and Rainsy and the CNRP have campaigned against Hun Sen’s longtime cozy ties to the Vietnamese government as well.

The rather unsatisfying answer is that we probably will never know the real outcome of Cambodia’s election, just like we don’t know whether the opposition won the Malaysian elections earlier this year or whether Henrique Capriles actually defeated Nicolás Maduro in Venezuela’s April presidential election or whether Armenian president Levon Ter-Petrosyan actually won February’s presidential election. In all four cases, there are credible accusations by the opposition that the governing party perpetrated varying degrees of fraud or other actions that made the elections somewhat less than free and fair. But there’s also a strong case that the government enjoys a wide berth of legitimate support.

So the truth is somewhere in the unknowable space between — unknowable not just to generalist observers like me, but even among Cambodia’s political elite, because a thorough audit of each vote is unlikely to happen, despite Rainsy’s calls for an independent committee to review the vote.

That is why Rainsy and the CNRP always faced an uphill battle in Sunday’s election, and it’s why Rainsy and his allies will likely never be able to find enough concrete proof of fraud sufficient to reverse the outcome — either because the fraud wasn’t as extensive as Rainsy claims or because fraud is particularly difficult to prove if electoral authorities do not cooperate.

Where does that leave the opposition? In a surprisingly good position for the next five years, so long as they can maintain unity.

After all, 56 seats is a vast improvement on the 29 seats that the CNRP held prior to the vote, and it will function as a bona fide opposition party in the National Assembly. Though the CPP will continue to boast the simple majority that it needs to pass legislation, it won’t have the two-thirds majority it needs to singlehandedly call a quorum of the National Assembly, which will give the CNRP real power to direct what happens within the Cambodian parliament. It also means that the CPP will not be able to singlehandedly amend Cambodia’s constitution.

And the election’s result has inadvertently scrambled the CPP’s long-term plans. Due to the nature of the proportional representation system used to elect the National Assembly, many of the more senior members of the CPP were ranked higher on party lists and therefore retained their seats. In contrast, the seats that the CPP lost all would have otherwise gone to the younger generation of CPP leadership. That includes the prime minister’s 31-year-old son, Hun Many (pictured above, center, with his father at right), who was in many ways his father’s surrogate campaigner throughout the election. So at a time when the CPP will face significant pressure to generate new ways of governing Cambodia, least of all with respect to economic policy, the party will have retreated to its geriatric core, its leadership based on the same networks of patronage that’s fueled its hold on power for the past five years.

One thing that Rainsy will not be tempted to do is join any form of power-sharing coalition with the CPP. Rainsy need look no further for a cautionary tale than that of FUNCINPEC, a royalist conservative party that had actually won the largest number of seats in the 1993 election. FUNCINPEC joined a turbulent and controversial alliance with the CPP following the 1993 election, with Norodom Ranariddh, the son of a former Cambodian king, who served as co-prime minister with Hun Sen. Factional fighting among the two parties came to a head in 1997, when until Hun Sen ousted Ranariddh in what is now seen as essentially a coup. FUNCINPEC lost seats in the following 1998 election, and it kept losing more support in each subsequent election, and it finally lost on Sunday the final two seats that it had held in the previous National Assembly.