I don’t mean to single out any particular post at any particular think tank, but a post from Chris Edwards at the Cato Institute today gets to the heart of why I am so distrustful of think tanks that lean so clearly either to the right or to the left.![]()

![]()

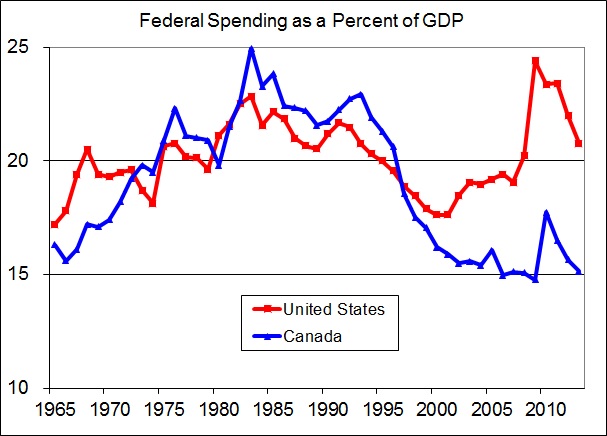

The Cato post comes after Conservative finance minister Jim Flaherty (pictured above) unveiled a budget on Tuesday that outlines further spending cuts designed to lower Canadian public debt more deeply, largely keeping to the same fiscal path that prime minister Stephen Harper’s government has set for years. The post, however, argues that the gap between federal spending in Canada as a percentage of GDP, which is lower, and federal spending in the United States, which is higher, is growing:

In Canada, federal spending fell to just 15.1 percent of GDP in 2013 and the government projects that the ratio will decline steadily to 14.0 percent by 2019 (p. 268). Federal debt as a share of GDP fell to just 33 percent this year.

Then follows some fairly massive generalizations about the state of Canadian and US federal spending over the past two decades and contemporary politics in both countries:

On federal fiscal policy, Canada has had pragmatic centrist leadership for the last two decades, with voters keeping the loony left out of power. In the United States, we’ve had power divided between centrist Republicans and loony left Democrats in recent years….

Pundits often claim that the Republicans are controlled by radical Tea Party elements. I wish that were true, but in terms of policy results there is no evidence of it. Republican and Democratic leaders are apparently satisfied with federal spending, deficits, and debt far larger than acceptable to the centrists in Canada.

And there’s a chart that proves it! See!? Canada good, US bad.

But there’s no indication that these numbers include spending at the provincial level, which is much more robust in Canada than corresponding spending at the US state and municipal level. It’s trend that has accelerated in the past two decades, as well, following Canada’s narrow brush with Québec’s independence referendum in 1995. That makes the chart essentially useless — it’s an apples-to-maple-leafs comparison. Continue reading The narrative of federal spending in Canada ignores provincial debt