You thought you were tired of all of the talk in the United States about the inevitability of a presidential run by former secretary of state Hillary Clinton in November 2016.![]()

But imagine if your next presidential election isn’t until May 2017 and everyone is already speculating.

That’s the case in France, where former president Nicolas Sarkozy is now even more likely to become the frontrunner for the 2017 race for the Élysée Palace after French officials dropped a criminal case against Sarkozy in the so-called Bettencourt affair.

Sarkozy was accused of soliciting L’Oreal heiress Liliane Bettencourt for secret campaign funds. The fundamentals of the scandal are similar to those for which former US senator and presidential candidate John Edwards stood criminal trial for soliciting secret campaign cash from banking heiress Rachel ‘Bunny’ Mellon, who was 96 years old at the time.

French judges are still pursuing an investigation over whether party officials in Sarkozy’s Union pour un Mouvement Populaire (UMP, Union for a Popular Movement) took advantage of Bettencourt’s mental frailty and advanced age in taking campaign donations for Sarkozy’s 2007 presidential campaign — in particular, former UMP treasurer Eric Woerth still faces criminal liability. But after Monday’s decision not to include Sarkozy’s name in the list of those who face liability, the former president has escaped the worst of his potential legal and political troubles for the foreseeable future.

That means that the single-most difficult obstacle between Sarkozy and a 2017 presidential bid is gone. Though he’s no longer mis en examen (placed under investigation) Sarkozy’s legal troubles haven’t totally evaporated, and he remains under a cloud of suspicion for a handful of other shenanigans, including allegations that Libya’s regime paid €50 million to Sarkozy’s 2007 campaign. But the Bettencourt affair was always the most serious case against Sarkozy.

As with the Clinton 2016 speculation in the United States, it’s folly to think that we can forecast with accuracy the dynamics of an election that’s years away. But it’s stunning in some ways that Sarkozy, who lost the May 2012 presidential runoff to François Hollande, the candidate of the Parti socialiste (PS, Socialist Party), remains such a strong challenger for 2017 just 17 months after leaving office.

Moreover, the specter of a Sarkozy return is affect French politics today (and not just 2017) by shaping the way that other top UMP officials posture and by placing pressure on the current, vastly unpopular Hollande regime — the possibility of a Sarkozy comeback also exerts a gravitational pull on the far right of French politics, too.

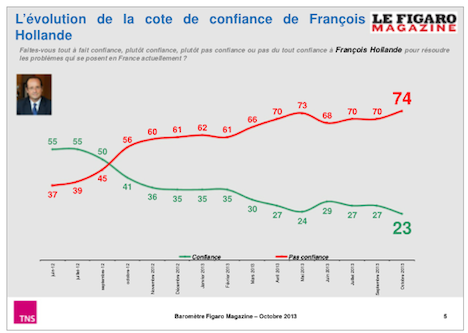

Only 23% of the French electorate has confidence in Hollande, according to an October TRS-SOFRES poll — Hollande has watched his popularity erode in record time to become the most unpopular president of the Fifth Republic:

France’s GDP growth dropped from 2% in 2011 to exactly 0% in 2012, unemployment has risen to 10.9%, and the economy’s doing not much better in 2013. Hollande was damaged almost from the beginning of his presidency over a nasty spat between his former partner, 2007 presidential candidate Ségolène Royal and his current partner Valérie Trierweiler. His bold effort to introduce a top income tax rate of 75% (of incomes over €1 million) invited capital flight and global ridicule — and a rejection by France’s top constitutional court.

His woes are so great that I wondered back in May whether the French left (and France, generally) might have been better off if Dominique Strauss-Kahn had survived his sex scandal to run for president.

Most immediately, of course, all of the ‘Sarko 2017’ talk serves to prevent the emergence of a truly post-Sarkozy center-right standard-bearer. Recall last November’s internal UMP primary to determine a new general secretary — right-wing candidate Jean-François Copé’s 50.03% was so narrow (and so challenged) by his opponent, the more moderate former prime minister François Fillon that the result threatened a UMP civil war.

Though the tensions subsided into more of a cold war than a civil war, there was always a sense that Copé was a stalking horse for a potential Sarkozy comeback — by defeating Fillon, Copé’s narrow win prevented Fillon from becoming the undisputed leader of the French right.

What was a Copé-Fillon showdown in 2012 has now transformed into a more open Sarkozy-Fillon showdown, with Fillon billing himself as the clean-break candidate for 2017, though Sarkozy himself has yet to decide whether to make a comeback bid for the presidency and is unlikely to join the political fray against either Fillon or Hollande anytime soon. An IFOP poll earlier this year showed that six out of 10 French voters preferred that neither Sarkozy nor Fillon run in 2017, though Fillon generally held higher approval ratings as prime minister than Sarkozy did as president, and there’s reason to believe he would have made a better candidate for the UMP in 2012 than Sarkozy.

Meanwhile, no consideration of the UMP’s machinations would be complete without considering the far-right Front national (FN, National Front) that, if anything, is gaining more strength than either the UMP or the Socialists. The far right notched a huge victory in a by-election in the southern canton of Brignoles on October 7, when the Front national candidate Laurent Lopez won 40.4% of the vote and will face a runoff against the UMP’s candidate Catherine Delzers, who won 20.8% (another far-right party, the Parti de France, won just over 9%.)

Despite Sarkozy’s lurch to the right on immigration and crime throughout his career, it didn’t stop Front national leader Marine Le Pen from winning 17.9% of the vote in the first round of the April 2012 presidential election. Among the factors that could push the UMP away from Fillon and toward a leader like Sarkozy or Copé in 2017 is the fear that a relatively moderate standard-bearer like Fillon would allow Le Pen to siphon even more support from the center-right.