Nearly 7,000 people have died in the Philippines since controversial president Rodrigo Duterte launched his ‘drug war’ last July, following his insurgent populist victory.![]()

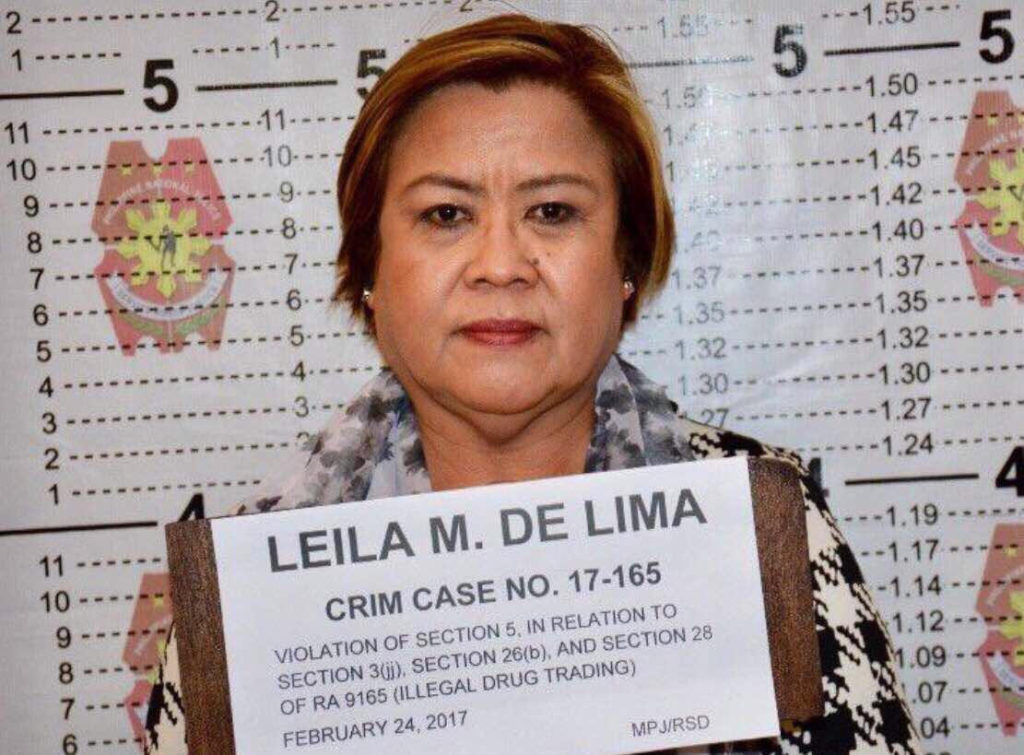

Last week, the chief domestic critic of Duterte’s human rights record, senator Leila de Lima, was imprisoned on charges of drug-related corruption — charges that have been widely met with disgust from human rights groups who say that her arrest is politically motivated.

Since taking power, Duterte has bragged about killing drug dealers himself when he served as mayor of of Davao City, all while encouraging police (and others) to engage in extrajudicial killings of suspected drug dealers. Last September, Duterte threatened to kill up to 3 million drug addicts, likening himself to Adolf Hitler.

As human rights watchdogs across the world continue to sound alarms, Duterte’s encouragement is already showing signs of spiraling out of control, with far more suspected criminals killed at the hands of vigilante groups than the official police. A South Korean businessman was strangled to death in policy custody, forcing even the sharp-tongued Duterte to pause for a moment. Nevertheless, Duterte has pledged to continue his aggressive campaign through the end of his six-year presidential term in 2022. His blunt speaking, often in vulgar terms, has brought him popularity with an electorate that elected him to be tough on crime and on drug use. Even as Duterte risks becoming an international pariah over human rights, Philippines still give him an 83% approval rating as of the beginning of 2017.

De Lima, who previously served as the chair of the Philippine Commission on Human Rights under former president Gloria Macagapal-Arroyo and as the country’s justice secretary under Benigno (‘NoyNoy’) Aquino III from 2010 to 2015, has called Duterte a ‘murderer’ and a ‘sociopathic serial killer.’ De Lima has led the fight against Duterte’s drug war from the Senate, the 24-member upper house of the Philippine Congress. Last September, Duterte’s allies removed her from the Senate’s Justice and Human Rights Committee, where she hoped to investigate the abuses of the drug war, most notably the extrajudicial killings.

The two politicians have a difficult history. In 2009, when she was still heading the human rights commission, De Lima first investigated rumors of ‘death squads’ in Davao City, where Duterte served as mayor for over two decades, for the first time in 1988, prior to his election to the presidency last May.

Upon surrendering to authorities Friday morning, De Lima embraced her new, jarring role as one of the world’s most prominent political prisoners:

It is my honour to be imprisoned for the things I am fighting for. Please pray for me…. They will not be able to silence me and stop me from fighting for the truth and justice and against the daily killings and repression by the Duterte regime.

Needless to say, De Lima — who as justice secretary investigated corruption charges related to Macagapal-Arroyo — already had one of the country’s most stellar records on human rights even before the Duterte administration began. De Lima stepped down as justice secretary in late 2015 to run for the Senate as a member of Aquino’s Partido Liberal ng Pilipinas (Liberal Party), a center-left, pro-democratic party that, under Aquino’s presidency, achieved high GDP growth and prosperity, though not enough to convince voters to hand another term to Liberal standard-bearer Mar Roxas. In the Philippines, senators are elected on a nationwide basis and, though she didn’t win the highest number of votes, De Lima won just enough to push her over the line into the last of the 12 available seats in last spring’s general election.

Since arriving in the Senate, De Lima has targeted Duterte’s drug war with a laser-beam intensity.

De Lima’s arrest, however, represents a darker twist for the Philippines. As Duterte’s diehard supporters cheer her imprisonment, no one else seriously believes that De Lima is personally involved in any kind of drug racket, and the Duterte administration has not produced any public evidence to suggest that there’s a legitimate case against the celebrated senator.

De Lima, who is divorced and the mother of two children, has been smeared in the press over an affair with her former driver, Ronnie Dayan. De Lima, who had previously demurred questions about her personal life, admitted the relationship in November after the current justice secretary, Vitaliano Aguirre II, threatened to air alleged sex-tape footage of De Lima and her lover on the floor of the Philippine Senate.

Though it’s a prudish and misogynist way to attack De Lima, the link is important because Duterte’s government alleges that Dayan was the supposed link between De Lima and drug dealers who contributed to De Lima’s campaign in exchange for leniency, including the ability to sell drugs with impunity inside the New Bilibid Prison during her tenure as justice secretary.

Philippine vice president Leni Robredo, a Liberal also elected last May (though candidates may run together on tickets, presidents and vice presidents elected separately and not jointly as a formal ticket), has increasingly opposed Duterte and the damage that he’s done to the rule of law and democracy. While Robredo agreed initially to serve in Duterte’s cabinet as the chair of the Housing and Urban Development coordinating council, she resigned in protest in December. Last week, Robredo added her voice to those slamming De Lima’s arrest, dismissing the case as political harassment:

Our history as a nation is marred by instances where government officials use the processes of criminal justice to cow, silence, and eliminate critics…. We cannot, and we must not, stand by and let this happen again. We must make sure that our government institutions remain uncorrupted and independent of each other, particularly when it comes to checks and balances in pursuit of accountability.

While the Duterte administration hasn’t provided any credible evidence linking De Lima to drug money, there’s a long history of Duterte threatening De Lima not to pick a fight with him, going back to before his inauguration.

At a political rally over the weekend, Aguirre asked the crowd who should be jailed next. The crowd responded with the name of Antonio Trillanes, another Duterte critic who has slammed De Lima’s arrest. Trillanes is a member of the center-right Partido Nasyonalista (Nacionalista Party), and he has nevertheless found common cause with De Lima, a Liberal senator. Duterte responded this morning by arguing that Trillanes is ‘too insignificant’ to be jailed.

Consider just how brazen that is.

Even in the context where critics at home and abroad are calling De Lima’s arrest politically motivated, the sitting justice secretary has no problem with a populist call to jail more critics, while the sitting president decrees which critics are too insignificant to jail.

Responsible for the deaths of over 7,000 citizens, most of whom died as a result of extrajudicial vigilante justice, Duterte has now jailed his most high-profile political opponent and brags about who will or will not be jailed next. It’s a tragic step backwards for the rule of law, and for a country with over 102 million people — the 12th most populous in the world — that makes it a major blow to liberal democracy worldwide. It’s doubly tragic because so many Philippines believe that Duterte is actually championing the rule of law in his efforts to eradicate drug dealers and other unsavory criminals.