Shortly after the December general election, I wrote that Spain faced three possible choices — a German-style grand coalition, a Portuguese-style ‘coalition of the left’ or a Greek-style stalemate and fresh elections. ![]()

Spain chose the Greek option.

Five months after a national election ripped apart Spain’s decades-long two-party system, the failure of the country’s four major parties to reach a coalition agreement means that Spain’s voters will once again go to the polls on June 26 for a fresh vote, after a deadline ran out on midnight Tuesday to find a viable government.

Notably, the rerun of Spain’s national elections will fall just three days after the United Kingdom votes on whether to leave the European Union, a critical vote for the entire continent.

The problem is that, with talks stalled for any conceivable governing majority, the Spanish electorate seems set to repeat results similar to last December’s election. For now, markets are not unduly spooked by the political impasse in Madrid, but continued uncertainty through the second half of 2016 could prove different if no clear government emerges from the new elections and, presumably, a new round of coalition talks brokered by Spain’s young new king, Felipe VI.

* * * * *

RELATED: Three choices for new fractured political landscape

* * * * *

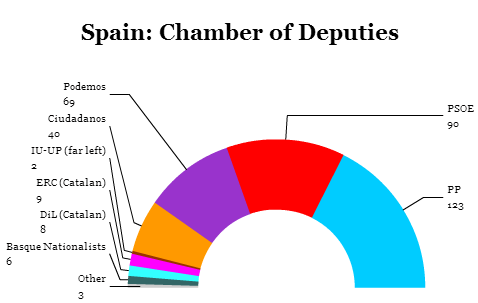

So who are the four major parties and how do they stand heading into the June vote?

Conservatives in the lead… for now

Prime minister Mariano Rajoy’s Partido Popular (PP, the People’s Party) won power in December 2011, and it emerged as the leading party after the December 2015 elections as well. Spanish voters credit Rajoy’s government with managing something of a long, grueling slog away from the brink of financial collapse. In avoiding a bailout, however, Rajoy managed to slash public spending at a time of deep economic pain. Even today, though the Spanish economy has started growing again, unemployment is still stubbornly high. April 2016 marked the country’s 66th consecutive month with a jobless rate higher than 20%.

Rajoy has had few options to form a coalition, in part because of Rajoy himself. From Galicia, Rajoy has never particularly inspired love from even his own party members, let alone from the electorate more generally. Socially, the 61-year-old Rajoy seems out of touch, and his government didn’t stop its more zealous conservatives from pursuing stridently anti-abortion laws and pro-bullfighting laws in a country that’s moved far to the left from the days of its Franco-era Catholicism. Corruption scandals dogged his party even before the December election and, in the ensuing six months, the former regional president of Madrid, Esperanza Aguirre, stepped down from her position as regional PP president earlier this year after a number of high-profile corruption cases.

Meanwhile, as a caretaker prime minister, Rajoy has shown little leadership beyond a call for Spain to end the ‘siesta,’ a practice that has long been in decline. He’s continued his ‘no negotiations’ approach to Catalan nationalism or any conversations about more regional autonomy or Spanish federalism, angering both Catalonia’s electorate and a government that intends to seek unilateral independence within a year’s time, ironically pushing the region closer to a rupture with Madrid.

A wide majority of the Spanish electorate associate the party with fiscal pain, but an even wider majority associate it with graft and corruption. Many of them also think it’s time for Rajoy to leave office. As the leader of the largest party in the 350-member Congreso de los Diputados (Congress of Deputies), however, it was well within Rajoy’s rights to reject calls that he step down.

But Rajoy is particularly unsuited to forming the kind of ‘grand coalition’ with his chief rivals, the center-left Partido Socialista Obrero Español (PSOE, Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party), in both tone and substance.

Instead, deputy prime minister Soraya Sáenz de Santamaría, a popular figure from Valladolid who has impressed as Rajoy’s deputy. Previously a quiet party aide, Sáenz de Santamaría, 17 years Rajoy’s junior, is a relative moderate and would appeal to voters as Spain’s first female prime minister. Unlike many of the dinosaurs in her party, she has no ties to the old Francoist regime nor to the corruption that’s clouded figures like Aguirre, former PP treasurer Luis Bárcenas and Spain’s former ambassador to India, Gustavo de Arístegui. While Spain hasn’t exactly been on the front lines of the refugee crisis, Sáenz de Santamaría has capably steered the government response over the last year. She handled the Ebola outbreak with similar competence, and she has developed a reputation as a thoughtful and personable technocrat.

Few doubt that the party’s fortunes would be much stronger if Sáenz de Santamaría were leading it into the June elections.

Socialists falling behind?

For months, the focus of coalition talks in Spain focused less on the caretaker, outgoing Rajoy government and more on the promise of Pedro Sánchez, the telegenic new leader of the PSOE.

On paper, Sánchez should have easily been able to find common ground with the anti-austerity Podemos (We can!) movement that sprang up in the aftermath of Spain’s financial and economic crisis, and the centrist and economically liberal Ciudadados (Citizens), another relatively new party.

Instead, Sánchez spent months running in circles. On one hand, he faced restraints from within his own party, given his own precarious position as leader. He was never expected to win the PSOE leadership in July 2014, and more powerful rivals like former defense secretary Carme Chacón and Andalusia’s regional president Susana Díaz remain viable alternatives. In particular, Díaz and other internal party opponents of Sánchez essentially vetoed his ability to negotiate with Podemos on Catalan independence (the movement would allow Catalans to decide for themselves whether to hold a referendum to separate from Spain) or to negotiate at all with separatist parties.

On the other hand, the rank-and-file members of Podemos widely rejected joining a PSOE-led coalition in a special vote in mid-April, and Sánchez never quite found a way to line up the various leaders of the Spanish left like António Costa did in Portugal last November.

Sánchez, from the outset, rejected a grand coalition with Rajoy’s Partido Popular, given the historic and cultural differences between the left and the right in Spain. But Sánchez also knows that in Greece, the more radical leftist SYRIZA supplanted the decades-long standard-bearer of the center-left, PASOK, after it joined a grand coalition with the Greek right. As it stands, Podemos threatens to eclipse the PSOE into second place in June. Sánchez, much like Rajoy, is less popular than his party rivals Chacón and Díaz. It’s not impossible to believe that Díaz, in particular, could emerge as a compromise prime ministerial candidate in grand coalition talks later this summer, just as it’s easy to imagine Sáenz de Santamaría in a similar role for the PP.

If he falls further behind — the 2015 election marked the worst showing for the PSOE in modern Spanish history — Sánchez will likely never have another opportunity to form a government.

Podemos hopes to consolidate opposition

Throughout the past five months, Pablo Iglesias and his Podemos movement resisted the opportunity to make a deal with the PSOE. In walking away from the negotiating table, Podemos has walked away from the opportunity to play a junior role in government and influence policy to help those left most behind by the economic misery of the last seven years.

Instead, Podemos hopes that it can emerge as the leading opposition force in June elections, thereby dictating its own terms to the PSOE and, possibly, the centrist Ciudadanos. That will not be easy, given that Podemos is more responsible than any other major party for Spain’s snap elections. Moreover, like the two traditional parties in Spanish politics, Podemos is increasingly fractured between its leader Iglesias and his deputy, Inigo Errejón.

One reason for their optimism is a proposed deal that would unite Podemos, which has claimed it is a non-ideological movement (despite a clear left-wing tilt), with the more established Izquierda Unida (IU, United Left), uniting the far left in a coalition of various national and regional groups similar to Podemos, including Coalició Compromís in Valencia and En Comú Podem, a left-wing group based in Catalonia. A joint Podemos-IU list would have an easier chance of winning second place and, therefore, be in a stronger position to negotiate its own coalition terms after June.

Ciudadanos likely to enter government no matter what

Meanwhile, Albert Rivera hopes that his Ciudadanos will improve, however modestly, on its December support. Polls show that it is well placed to do so, given its willingness to enter into negotiations with the PP, the PSOE or Podemos. It was an initial deal between Ciudadanos and the PSOE in February that came closest to fruition — until, that is, the PP and Podemos both rejected it.

If, as polls show, the June elections leave the four parties essentially stuck, each with support of 15% to 25%, it seems very likely that Rivera will be central to fresh coalition negotiations. If he can convince traditional Partido Popular voters to abandon tradition and support his party, he could even wind up as prime minister, though not all Spaniards have warmed to his platform of widespread economic liberalism, labor reform and hopes of modernization.