If, contrary to the United Kingdom’s new fixed parliament law, the British went to the ballot box tomorrow, most polls show that the result wouldn’t change much.![]()

That is, a Conservative government with which Britons are less than enthusiastic.

Nearly eight months into Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership of the opposition, center-left Labour Party, there’s no indication that the electorate has warmed to Corbyn’s hard-left policy views, nor any likelihood that Corbyn’s own critics on the back benches, populated with many of the figures who once wielded power in the ‘New Labour’ years under Tony Blair and Gordon Brown, trust him as their standard-bearer.

The nearly flawless campaign of the left-wing (though not always Corbynite) Sadiq Khan, Labour’s candidate in London’s mayoral race, will give Corbyn at least one highlight in the coming May 5 regional elections. But Labour faces potential routs across England and, most damningly, failure to make any real progress against Scottish first minister Nicola Sturgeon, with the Scottish National Party (SNP) apparently heading to a romp in Scottish parliamentary elections, with a nearly 30% lead over the Scottish Labour Party.

All of which will put even greater pressure on Corbyn’s leadership. Though Corbyn entered the Labour race with no hope of actually winning, there’s little that the party’s Blair/Brown/Miliband/Cooper wing (which dominates the parliamentary caucus, though not the Labour grassroots) can do unless or until Corbyn loses popularity among the Labour faithful that delivered him to the leadership last summer. It’s not an outcome that appears likely to happen anytime soon.

Nevertheless, even if Labour suffers an especially poor night on May 5, Corbyn has a tailor-made opportunity to save his leadership. In the process, Corbyn might also transform his image among a British electorate that remains highly skeptical of ever giving Corbyn the keys to 10 Downing Street.

It all rides on how Corbyn wages the Labour campaign to remain within the European Union in the coming June 23 referendum. If he succeeds, politically and substantively, Corbyn could both silence critics in his own party and, for the first time, introduce himself as truly prime ministerial material.

Corbyn came out swinging against Brexit in a major speech on the referendum last week, with a view toward reforming the European Union. The speech, charitably, met mixed reviews. Corbyn is clearly not a man who relishes what ‘European union’ has come to mean today. It’s no secret that Corbyn, for years, was skeptical about European integration. Corbyn has long derided the European Union as a mechanism for enforcing orthodox economic policies. It’s of course true that Corbyn is instinctively far more wary of the European Union than his business-friendlier rival, prime minister David Cameron.

To a degree, Corbyn’s fears have been proven right. In the aftermath of the 2009-10 eurozone sovereign debt crisis, the response of the European leadership was to produce a fiscal austerity compact that gave Europe’s leaders, for the first time, real power to enforce rules limiting member-state budget deficits, all while forcing sometimes draconian austerity on countries like Greece and Portugal in exchange for the bailout funds to keep them afloat (and in the eurozone).

There’s certainly a strain of ‘Old Labour’ that’s always been hostile to British participation in the European single market, and that’s always been Corbyn’s wing of his party.

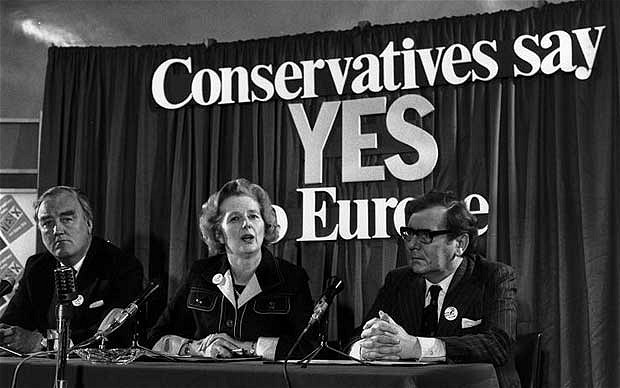

When Conservative prime minister Edward Heath, at long last, negotiated British entry into the European Economic Community in 1973, it was a Labour prime minister, Harold Wilson, who waged two successful 1974 election campaigns on a promise to put the Europe decision to a vote of the British people. By the time his government scheduled a referendum in 1975, Wilson (and much of his cabinet, along with a much more united Conservative Party) supported the ‘yes’ side that wanted the United Kingdom to remain party of the European common market. Remarkably, even Margaret Thatcher supported the ‘yes’ camp. The ‘no’ camp featured some right-wing nationalists like Enoch Powell, but its power came mostly from strident leftists like Michael Foot, who would become Labour’s leader in the early 1980s, and Tony Benn, the ideological forerunner of Corbynism.

The 1975 referendum ultimately passed by a margin of 67.2% to 32.8%. In the following three decades, Labour (mostly) united behind a Blairite, pro-European agenda while the Tories, famously, tore themselves apart over Europe in the 1990s. Even today, Cameron is competing in the Brexit campaign against ambitious ‘outers’ like outgoing London mayor Boris Johnson, justice secretary Michael Gove and many Tory backbenchers who have never particularly loved Britain’s ties to Brussels (or, increasingly, the obligations to Europeans who want to live and work in the United Kingdom).

Corbyn, however, at least before his leadership election, was always more comfortable with the anti-Europe forces of his party. And that’s exactly why Corbyn is so well-placed to become the most important figure in convincing undecided voters to stick with Europe.

From the beginning of his leadership, Corbyn has clearly been pained to reconcile his leadership with his private views on Brexit. Almost immediately after his Labour victory last September, he had to issue an embarrassing statement that Labour would campaign to remain part of the European Union to keep Hilary Benn, the late Tony Benn’s more pragmatic son, onside as his shadow foreign minister.

But Corbyn rose to the leadership because Labour’s voters saw him as a trustworthy, relatable and decent person. Many voters might disagree with Corbyn’s quite leftist agenda, but few dispute that he is painfully, often awkwardly, earnest. He lacks the easy bonhomie of Nigel Farage, the stridently anti-Europe leader of the United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP), or Boris Johnson’s shaggy-haired charisma, or the toff polish of top government officials like Cameron, chancellor George Osborne and even former Liberal Democratic leader Nick Clegg.

In the fight over Brexit, though, that gives Corbyn the right kind of authenticity. No one believes Corbyn is sanguine about the direction of EU policy, and that gives voters a reason to trust him. If Corbyn, so lukewarm about the European project after decades, still manages to oppose Brexit, it’s a powerful statement. But it’s even more powerful because no one believes Corbyn has a personal stake in the Brexit fight quite like the other players:

- Farage, of course, has made his entire career on outrage over Brussels and Berlin.

- Cameron, almost certainly, would have to resign if voters choose to leave the European Union, especially after his efforts to negotiate a better deal.

- Johnson, Osborne and everyone else in the Conservative Party are using the referendum as an opportunity to position themselves to succeed Cameron as Tory leader in the next general election.

- While Sturgeon and the SNP are very much pro-European, they also know that Brexit would constitute moral grounds to demand a fresh referendum on Scottish independence.

Corbyn is the only honest broker.

No one believes (today, anyway) that he’s really going to last long enough to wage Labour’s campaign in the 2020 election. More importantly, however, his longstanding ambivalence about Brexit and the European Union makes him a much more credible advocate in the referendum campaign, giving him the humility and humanity to win over voters who are genuinely torn — in much the same way that former prime minister Gordon Brown, as proud a Scotsman as anyone, was such an effective advocate in the final days of the 2014 referendum on Scottish independence.

Along the way, Corbyn can demonstrate not only to disaffected Labour voters, but to UKIP voters (and Liberal Democratic voters, Scottish and Welsh nationalists, and even soft Tory voters) that he has the leadership skills and instincts of a prime minister, never mind that he’s always going to be far to the left for much of the electorate. Thatcher’s hard-right views, after all, didn’t stop her from three terms in power.

The hopes of London’s financiers and the entire British business establishment, not to mention the legacy of Cameron’s career, may ultimately, ironically, rest on Corbyn’s shoulders.

Labour’s leader must be as aware as anyone that those forces, against which he’s fought tirelessly his whole career, might well depend on Corbyn to deliver the day against Brexit. It’s the kind of sacrifice and leadership from which prime ministers are made. If it does take Corbyn, after everything else, to turn back the Brexit threat, no one will look at him in the same light again. Though Corbyn won the Labour leadership contest last year, it might be the Brexit vote that, at long last, transforms him truly into his party’s leader — and a prime ministerial contender.

Brilliant