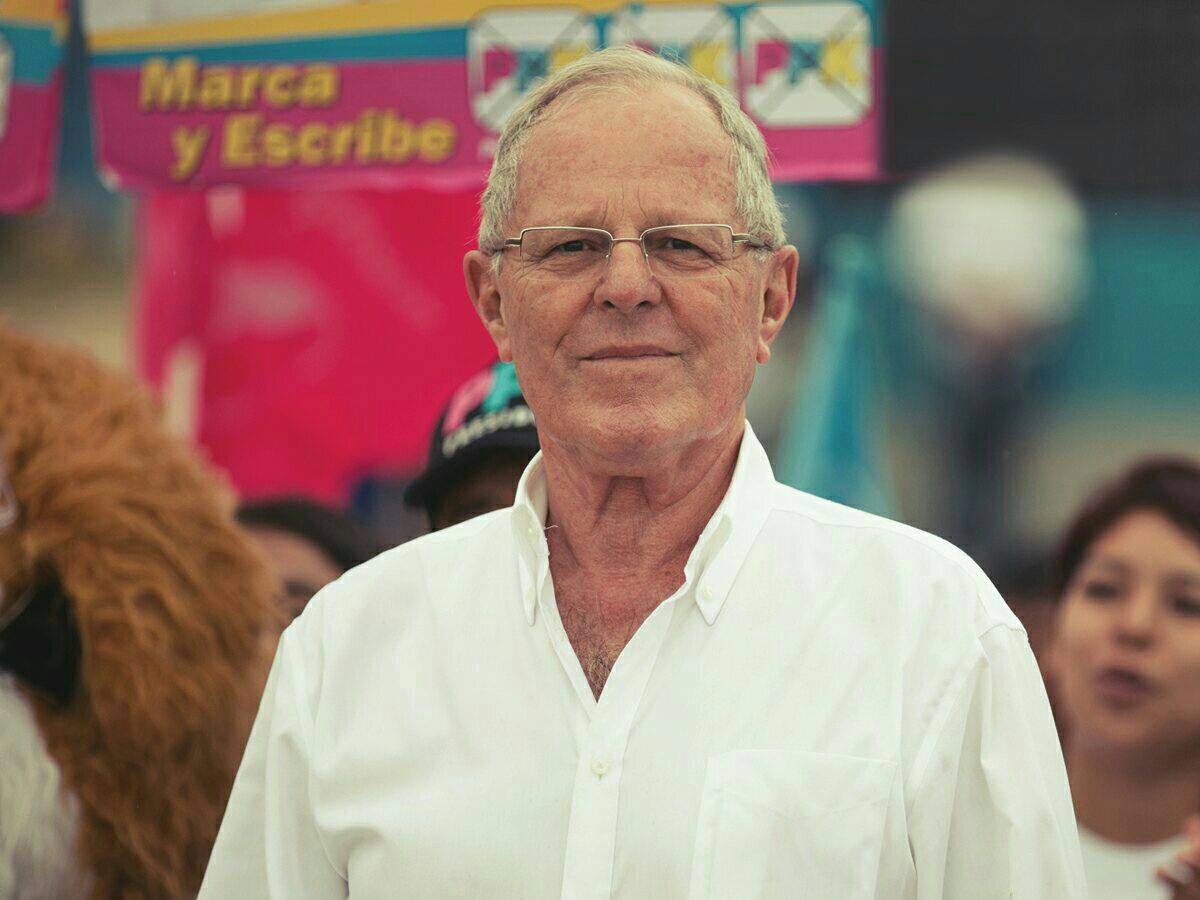

For Pedro Pablo Kuczynski, the hardest part of Peru’s two-stage presidential election might be making it into June’s runoff. ![]()

It was no surprise that Keiko Fujimori, the daughter of former president Alberto Fujimori, a controversial figure now serving a prison sentence for human rights abuses during his time in office from 1990 to 2000, would win the first round of the election on Sunday.

Quick counts and initial results show that Fujimori, as predicted, easily won the first round with around 39.5% of the vote.

* * * * *

RELATED: Fujimori’s daughter leads as

Peru faces June presidential runoff

* * * * *

Kuczynski, nearly universally known as ‘PPK’ in Peru, was winning around 23.7% of the vote, enough to edge out the third-placed candidate, left-wing Verónika Mendoza, who was winning around 17.1% of the vote.

The results all but assure that Kuczynski will emerge as Fujimori’s challenger in the June 5 runoff — a choice that many Peruvians wanted in the 2011 election.

Five years ago, it was leftist Ollanta Humala who won the first round, while Fujimori placed second, eliminating Kuczynski from the runoff in what many voters considered a worst-case scenario. On one hand, they could support a former army officer with a spotty military record and with ties to the radical left; on the other hand, the daughter of an anti-democratic authoritarian.

PPK’s apparent victory over Mendoza this year means that the 2016 runoff will be far less ideological than the 2011 runoff, instead featuring two candidates who espouse the kind of orthodox economic views that have dominated Peruvian governance since since the 1990s (even, perhaps surprisingly, during the Humala administration).

One of the central policies of Keiko Fujimori’s campaign has been a promise to use some of Peru’s $8 billion ‘rainy-day’ fund to stimulate spending on infrastructure and other projects to develop rural Peru. That means she will, on economic matters at least, be running to the left of PPK, who has called for budget discipline and pro-business policies that include a modest sales tax cut. Both candidates have signaled that they want to curb Peru’s growing coca production, and both candidates want to work to give local communities a greater share of profits from gold and copper mining that have boosted the Peruvian economy.

Polls show that the runoff will be competitive, despite Fujimori’s wide first-round victory. An average of four polls conducted in April before Sunday’s first-round voting gave Fujimori a statistically insignificant lead of 41.6% to 39.8%.

A CPI poll from earlier this month showed Fujimori leading PPK in a runoff scenario by 43.5% to 38.0%. The latest April Ipsos poll showed PPK leading Fujimori (43% to 41%). The latest April GfK poll gives Fujimori a similarly slight edge (41% to 38%). The latest April Datum poll gives Fujimori a minor lead (41% to 40%).

PPK’s challenge for the next two months will be to coalesce voters against Fujimori by harnessing fears that she could release her father from prison, return his advisers back to power and endanger Peruvian democracy. He will need to build on fears that a vote for Fujimori would take Peru back to the days of authoritarianism and (even deeper) corruption.

Many Peruvians already harbor serious doubts about Fujimori, who is clearly having trouble winning an absolute majority of the electorate and who narrowly lost the 2011 election to Humala who, at face value, seemed a far easier challenger than PPK.

Fujimori’s challenge will be to reassure voters that she doesn’t represent a regression of democracy. A formal apology for the excesses of her father’s regime and a promise not to pardon or otherwise work to release her father from prison, convicted for organizing anti-rebel death squads, would go a long way. His dogged pursuit of the Maoist Sendero Luminoso (Shining Path) largely neutralized the guerrilla threat but his successors, including Humala, have struggled in their efforts to eradicate Shining Path once and for all.

By doubling down on her populist spending plans, Fujimori can also hope to convince swing voters that PPK’s policies will do nothing to help Peru’s poor. With neighboring economies in decline, she can argue that the past 15 years of economic growth haven’t filtered down equally to all Peruvians. Rural voters, polls show, prefer Fujimori by a larger margin, and they also preferred Mendoza to PPK (especially in the country’s south). Polls also show that wealthier voters prefer PPK, while the poorest voters preferred both Fujimori and Mendoza — by wide margins.

Moreover, as a former World Bank economist and US-based investor, PPK can easily be caricatured as an out-of-touch globalist in thrall to international interests. At age 77, PPK would be the oldest president in modern Peruvian history, and his lengthy residence in the United States could harm him among nationalist voters.

Two key figures could play an important role in swinging undecided voters. Mendoza, the third-placed candidate, whose support could bring along Peru’s most leftist voters. They will now have to decide whether to vote in the runoff and, if so, which of the two center-right candidates to support. Another is Julio Guzmán, a technocrat and economist who served as a deputy minister in the Humala administration. Guzmán was well on his way to the runoff until March, when Peru’s elections board shadily disqualified him from the race on a technicality.

Alfredo Barnechea, a journalist and former member of the Peruvian Congress, won around 7.5%. Two former presidents fared even more poorly. Alan García, president from 1985 to 1990 and again from 2006 to 2011, won around 6.1% of the vote. Alejandro Toledo, a center-left figure and Peru’s first indigenous president (from 2001 to 2006), won just 1.2%.