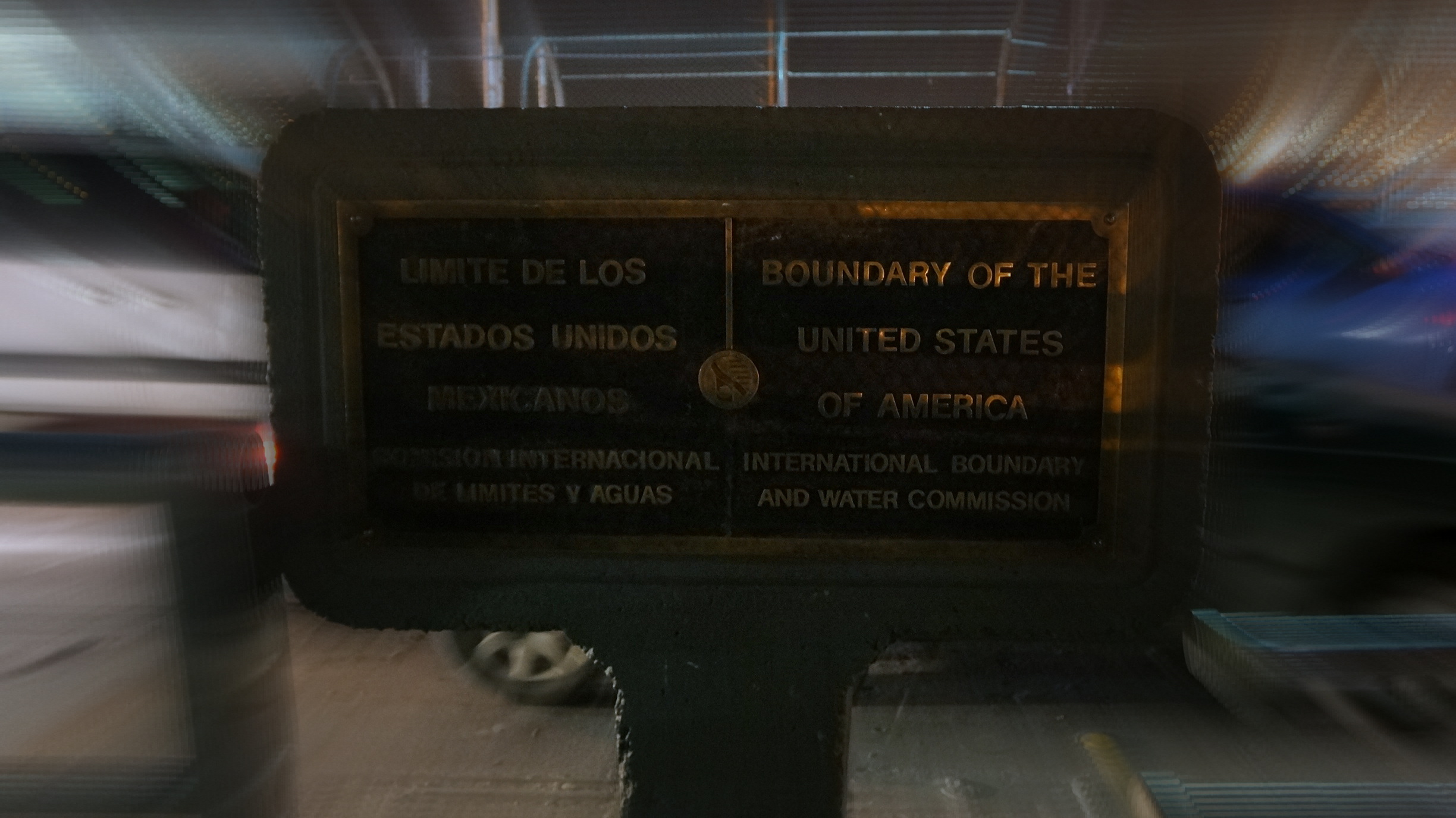

Every day, thousands of El Pasoans and Juarenses cross from their relative sides of the city across an international border as part of their daily commutes. ![]()

![]()

No two communities along the 1,933-mile border between the United States and Mexico are more interconnected than El Paso and Ciudad Juárez — not San Diego/Tijuana and not Tucson/Nogales. Geography explains the difference in part, because El Paso and Juárez began as the same city, ‘El Paso del Norte,’ founded by Franciscan friars from Spain in the 17th century. Throughout centuries of Spanish rule, the more rapid development took place south of the Rio Grande (in today’s Juárez), with the northern bank a sleepy outpost still subject to Apache, Comanche and other raids.

In 1824, upon Mexican independence from Spain, Paso del Norte was transferred from the territory of New Mexico to the state of Chihuahua — a crucial move for the area’s future. If it hadn’t happened, Paso del Norte might otherwise have remained a city intact within Mexican borders.

Historically, then, the region was never part of Texas. When American settlers finally managed to annex Texas away from Mexico in 1836, the decade-long Republic of Texas didn’t include what is today El Paso. But shortly after Texas’s admission to the United States in 1845, the new Texas settlers were anxious to expand the southern Texan border from the Rio Nueces to the Rio Grande, and that push helped catalyze the coming Mexican-American War. In the war’s aftermath, Texas managed to negotiate extending west Texas all the way to Paso del Norte, in hopes of benefiting from cross-border trade and to give Texas a link to the intercontinental trade hub at Santa Fe (now part of the United States through the Mexican Cession).

At the stroke of a pen in 1850, then, the northern banks of Paso del Norte were not only a part of Texas, but of the United States as well. After Texans initially incorporated the city of El Paso in 1873, the city of Paso del Norte changed its name to Juárez in 1888, in honor of Mexico’s indigenous, liberal president of the 1860s.

But the 1850 compromise also created something absolutely unique in American urban history — a city (yes, one city) divided by an international border.

Until 1917, though, there wasn’t much of a border at all.

It took the unrest of the Mexican revolution of the 1910s (that all too often crossed the US boundary, notably Pancho Villa’s raid of Columbus, New Mexico, in 1916, an act that attracted a response from US general John Pershing). With the Zimmerman telegram‘s publication, and as the United States edged toward joining World War I, securing the southern border from German perfidy suddenly became a national priority.

As national borders became more fortified in the 20th century, the border between El Paso and Juárez was no exception. But just as Mexicans decamped for El Paso during the unrest of the Mexican revolution (the battle of Juárez in 1910 and 1911 was one of the earliest military engagements), Americans would shortly find Juárez a refuge of another sort as Prohibition began.

The 2001 terrorist attacks led to a greater border presence though, unlike many other border crossing after the September 11 attacks, the El Paso-Juárez crossing remained open in the immediate aftermath of the attacks. Post-9/11 border security, according to residents on both sides, resulted in far longer lines, especially those to return to the United States. That, however, didn’t stop a deluge of Juarenses across the border in 2010 and 2011 when drug violence between the Sinaloa cartel and the local Juárez cartel reached its zenith, exacerbated by Mexican president Felipe Calderón’s militarization of the country’s anti-drug efforts.

Today, with violence down (for now) from a high of around 3,000 homicides to just 311 last year (a bit less than Chicago), more El Pasoans are once again crossing the border to Juárez. A few work there, but far more enjoy the nightlife, go to church with families that have transcended borders — a people not fully American or Mexican, but appropriately fronterizo.

Crossing the border, as a white American, at least, is a straightforward affair, and you can easily walk from downtown El Paso nearly seamlessly to the centro of Juárez in a leisurely afternoon walk.

When you walk from the El Paso side to the Juárez side, you merely walk across the bridge, paying a small toll — $0.50 into Mexico and $0.25 back into the United States. (Have exact change, at least when returning to the United States). There isn’t a Mexican immigration presence nor is there much of a customs presence.

What’s so interesting about El Paso and Juárez is that the two cities do flow seamlessly into each other, not just geographically, but culturally and economically, too. El Paso has always featured a heavily Latino population that’s become more pronounced in the last half century, rising from 57.3% of all residents in 1970 to 80.7% in 2010.

Despite the similarities, there’s a clear economic disparity between the two halves of the bi-national city. Though the per-capita income of El Paso County is just $13,421, and the per-capita income of Chihuahua state (as of 2007) was 136,417 pesos, equivalent today to just $7,500, though the drug war violence, peso devaluation and global financial crisis didn’t exactly boost Juárez’s economy, which continues to recover.

Juárez, moreover, was never the political center of Chihuahua (that’s the more sore southern capital, Ciudad Chihuahua), despite its role in cross-border trade (and wit the rise of low-wage maquiladoras, owned by American companies for cheaper manufacturing).

Binational cities, of course, aren’t the only cities to feature massive income and wealth inequality. I think most immediately of the different outcomes between much of Washington, D.C., and Wards 7 and 8, predominantly African-American and east of the Anacostia River that divides the US capital.

What’s more, the best views of ‘El Paso’ necessarily include Juárez. Want a nice sunset view? Most of it’s going to be south of the Grande.

Even from perhaps the most famous and stunning vista in El Paso, Scenic Drive, the view necessarily conflates El Paso and Juárez, though light density tells much about the differences in the cultural and economic life of the two halves of the city.

Coming back from Juárez to El Paso is somewhat more complicated, though as a pedestrian, there’s very little waiting time involved. It’s no more or less intense than the process of flying back to the United States from any other country. The experience of Mexicans is more intense, however, according to many with whom I spoke. (And, of course, entire books discuss the cross-border experience of Mexicans.)