What if Haiti rescheduled a presidential election and no one showed up?![]()

With outgoing president Michel Martelly due to leave office on February 7, the government last week rescheduled a delayed presidential runoff for January 24 — potentially the last possible date, according to government officials, to ensure a smooth transition from Martelly to a successor.

But the legitimacy of the new runoff isn’t assured. The first round’s runner-up has not yet committed to participating in the campaign, given doubts about fraud and unfairness from the prior round, leaving in question the January 24 vote’s integrity. The runoff was also set, after July and October voting, to finalize the composition of a new parliament after nearly a year of legislative vacancy.

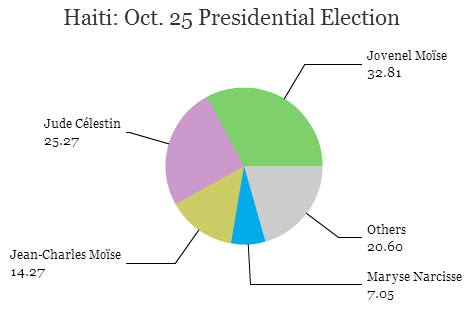

The decision leaves banana exporter Jovenel Moïse, the winner of the first round, a political neophyte close to Martelly, as the only candidate running and, accordingly, even more likely to win the runoff. Under such dubious conditions, however, his presidential mandate will be virtually meaningless if the opposition’s supporters boycott the vote in a country where only about one-quarter of all voters even bothered to turn out in the first round in October.

Moïse’s opponent in the runoff was supposed to be Jude Célestin, who served as a former minister under Martelly’s predecessor, René Préval, but he hasn’t yet committed to joining the runoff, which was originally scheduled for December 27. Fraud allegations forced Martelly’s government to postpone the final vote in order for a hasty commission to look into the voting practices of the first round.

The commission’s report found that there was a ‘high presumption’ of fraud, calling for a wider (and presumably, lengthier) review of the voting to determine the nature of the irregularities and policies to fix Haiti’s electoral machinery in the future. The commission, with just a couple of weeks to make its findings, pinned blame on the country’s existing electoral commission, casting doubts on its ability to administer the runoff without similar problems.

For now, Célestin hasn’t committed to the runoff, and he’s demanded that Haiti’s government implement the commission’s recommendations in time for the runoff, including a broader ‘political dialogue’ that Célestin claims isn’t happening. But the logistics of doing so would postpone the runoff for weeks or even months, well beyond the end of Martelly’s term. Célestin, who hasn’t formally withdrawn from the runoff, isn’t yet campaigning for the runoff, either, telling the Miami Herald on Thursday of last week that Haiti will be holding a runoff with just one candidate, highly suggesting that he will not easily contest the vote. That means that every day that passes is a day of confusion throughout the country, which may or may not conduct a contested election in two weeks.

If Célestin does formally withdraw, it means that the third-placed candidate would have the opportunity to join the runoff; for now, however, many of the other 54 candidates from the first round have joined forces with Célestin, decrying the conduct of the October 25 vote, including the third-placed Jean-Charles Moïse and the fourth-placed Maryse Narcisse, an ally of former president Jean-Bertrand Aristide, who held the presidency several times between 1991, following what most observers deem Haiti’s most free and fair elections, and 2004, when a coup forced him from power for good.

Adding a twist to the contest, Célestin himself was seen to have benefited from fraud in the 2010 presidential election. After the first round of that vote, Célestin agreed to withdraw from the second-round runoff, paving the way for Martelly (who finished in third place) to win the presidency in March 2011. So while it’s Célestin crying foul in 2015, it was Célestin’s opponents who were crying foul at the time of the last election.

Haiti is still struggling to recover from the devastating January 2010 earthquake that destroyed parts of the capital of Port-au-Prince and a debilitating cholera outbreak that followed, transmitted, it is believed, from south Asian aid workers assisting the United Nations rebuilding mission.

If Martelly leaves office without a clear successor (or with a disputed one), it could leave Haiti’s government even more paralyzed. Long-delayed parliamentary elections over the course of 2015 were held to elect a new legislature — delays meant that the prior parliamentary mandate ran out at the end of 2014, meaning that Martelly ruled the country by executive decree for the past year.

The 2015 elections, at long last, were suppose to transcend those troubles. Instead, as the voting flows into 2016, Haitians may find themselves doubling down on uncertainty.