It wasn’t supposed to be this way.![]()

Nearly five years ago, when Haitians elected political newcomer Michel Martelly, a well-known compas singer also known to Haitians as ‘Sweet Micky,’ there was every expectation that a new government, backed by massive amounts of international aid and a renewed commitment to transcend the devastating January 2010 earthquake’s destruction, might finally end Haiti’s cycle of poverty, corruption and dependence.

Instead, nearing the sixth anniversary of that earthquake, tens of thousands of Haitians are still displaced after Port-au-Prince, the Haitian capital, was leveled. A standoff with Haiti’s congress ultimately delayed 2012 legislative elections for years, forcing Martelly to spend the last year in office governing without a valid legislature in a state of quasi-permanent constitutional crisis.

Elections on August 9 and October 25 were supposed to fix that by electing both houses of the Parlement Haïtien (Haitian Parliament) and the October election was set to select Martelly’s successor. The October voting initially seemed to go well, and the first reports gave no signs of massive fraud or political violence, both of which have marred elections in recent years.

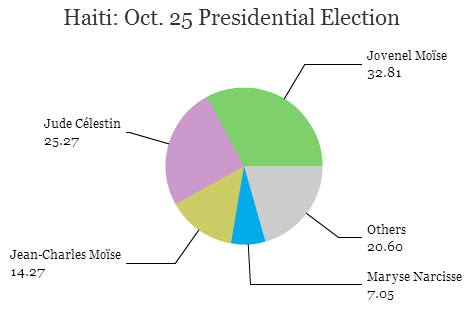

But as it became clear that the December 27 runoff would feature Martelly’s preferred candidate, Jovenel Moïse, and 2010 contender Jude Célestin, a former minister with close ties to Martelly’s predecessor, René Préval, many of the remaining candidates cried fraud. With protests on the rise, the Haitian government announced last week that it was postponing the December 27 runoff indefinitely pending the report of a five-person electoral commission, hastily appointed by Haitian prime minister Evans Paul last week.

Jean-Charles Moïse, running as something of a newcomer and a fierce critic of the Martelly administration, placed third, and he and Célestin have railed against the government’s allegedly fraud, along with many of the other candidates (54 in total) who failed to make the runoff. Even the initially sanguine reports of international observers gave way to gloomier verdicts about the October vote’s integrity:

Not only were voting procedures inconsistently applied at poorly designed polling stations, the report notes, but the widespread use of observer and political party accreditation led to people voting multiple times and potentially accounts for as much as 60 percent of the 1.5 million votes cast.

Martelly’s administration, however, has little time to investigate and find any conclusions about fraud. Per the terms of the Haitian constitution, Martelly must hand over power to his elected successor on February 7, which means that, according to Paul, the last safe date to hold the runoff is on January 17.

Haitians may be right to be skeptical about Moïse, the candidate of Martelly’s Parti Haïtien Tèt Kale (PHTK, Haitian ‘Bald Head’ Party), formed in 2012. With constitutional term limits that prevent Martelly running for reelection, it isn’t the first time that an outgoing Haitian president has attempted to groom a friendly successor. A political neophyte, Moïse has since 2012 led NOURRIBIO, an effort designed to boost Haitian agricultural development and claims to have developed 3,000 jobs in the agricultural sector. Though Moïse’s vision of a more prosperous Haiti through a growing, thriving and sustainable agriculture industry may well be the country’s path to economic stability, there’s little trust that Moïse has the skills to lead Haiti there, given the endemic corruption surrounding the government.

It would be ironic, however, if Célestin were to be the chief beneficiary of the Haitian electorate’s doubts, because he was essentially playing the same role in the 2010 presidential campaign that Moïse is playing today.

As the candidate backed by the outgoing Préval administration, Célestin muscled his way into a runoff after the first round of the lat presidential election. Célestin placed second, well behind Mirlande Manigat, the wife (now widow) of a former president, Leslie Manigat, who held power briefly after the troubled 1988 elections. But the outcry from both Haitians and the international community over alleged fraud was so intense that Célestin agreed to withdraw from the March 2011 runoff, and the third-placed Martelly overwhelmingly defeated Manigat.

The lack of enthusiasm for either of the two main candidates might explain why voter turnout (26%) was so low in the October vote.

Even aside from the drama over fraud and Célestin’s near-involuntary withdrawal from the runoff, the 2010 election took place under some of the most dramatic conditions in recent Haitian history. The election kicked off with an ill-fated campaign by the US-based hip-hop performer Wyclef Jean, a Haitian-American who left the country at age nine who speaks neither French nor Kreyòl, was ultimately disqualified by Haiti’s electoral commission five months before voting began. It took place under a cloud of United Nations mishaps, most notably a cholera outbreak that traced its origins to UN workers from South Asia.

Jean-Claude ‘Baby Doc’ Duvalier, the dictator who ran the country from 1971 until his 1986 overthrow, returned to the country from exile in France in January 2011 as the runoff campaign was just taking shape, stoking fears that he might try to engineer a political comeback and undermine his struggling transition to democracy. Jean-Bertrand Aristide, who served as Haiti’s presidency three times between 1991 and 2004, returned two months later after a decade in exile after a 2004 coup ended his third and final stint in power.

The 2015 election, however, featured none of this drama. Wyclef Jean, who has continued to advocate for his home country, quietly endorsed Célestin earlier this year. Duvalier died in October 2014, ending his family’s once-brutal hold on Haiti. Maryse Narcisse, the candidate of Aristide’s party, Fanmi Lavalas (‘The Flood’), managed just 7.05% of the vote in the first round of the presidential vote.

Martelly has faced growing criticism over the failure to hold elections in the first four years of his administration, and he has faced the standard litany of complaints about corruption and ineffectiveness that have plagued nearly every Haitian administration in recent memory. Martelly has also had to face allegations of ties to Duvalier, and high hopes that the Haitian government would prosecute Duvalier for his crimes against the country faded under Martelly’s administration as investigations and court hearings never seemed to gain sufficient momentum for real charges against the former dictator.

Haiti, a country of over 10.5 million people with a rich and proud history, which gained its independence in 1804 from France after a widespread slave revolt under its founding father, Toussaint Louverture, struggled throughout the 19th and 20th centuries from hostile foreign relations with Europe, internal strife, autocratic dictatorships like those of the Duvalier family, frequent (if unhelpful) US military intervention and environmental and humanitarian crises. Today, it’s still the poorest country in the Western Hemisphere, with a nominal GDP per capita of around $800.