As predicted, Spain’s messy general election resulted in no clear winner, and none of its two largest parties could claim a majority in the lower house of Spain’s parliament.![]()

What’s more, though two upstart parties upended the political status quo that’s existed for nearly 40 years in Spain, neither did so well that they can form a government — or even serve as a kingmaker for one of the two established parties.

While the conservative Partido Popular (PP, the People’s Party) emerged with the largest share of the vote, prime minister Mariano Rajoy has plenty of reason to despair. Much of the party’s support comes from older voters in the Spanish countryside, and the PP benefited from an electoral system that delivers slightly more seats to parties with support outside Spain’s urban centers. Nevertheless, he has lost his absolute majority, dropped 64 seats and, worst of all for Rajoy, there’s no clear or easy path to a governing majority. Though Spain’s economy has stabilized under the past four years of PP rule, unemployment remains staggeringly high (21.2%). The party’s leader since 2004, Rajoy might ultimately be pushed aside during coalition talks for a younger or more charismatic leader, like deputy prime minister Soraya Sáenz de Santamaría.

* * * * *

RELATED: Spain readies for historic four-way election on December 20

RELATED: Can Felipe VI do for federalism

what Juan Carlos did for democracy?

* * * * *

Meanwhile, the center-left Partido Socialista Obrero Español (PSOE, Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party) suffered its worst defeat since the transition to democracy in the late 1970s. Its new leader, Pedro Sánchez, a moderate economist, simply could not convince voters to look beyond long-simmering corruption scandals (which, by the way, also plague Rajoy’s party) and the record of the prior PSOE government, which took the first steps toward the path of austerity measures in the aftermath of the 2009-10 eurozone debt crisis.

Indeed, the PSOE just barely outpolled Podemos, an anti-austerity alternative that burst onto the Spanish political scene in 2014, embracing the anti-establishment protests of the ‘indignados’ movement. Despite leading polls earlier this year, Podemos crashed as fears grew that it would cause the kind of economic pandemonium that plagued Greece after the election of the far-left SYRIZA this year. Its leading spokesperson, Pablo Iglesias, began to moderate his movement’s rhetoric, and rallied to a strong third-place finish.

The center-right liberal Ciudadanos (‘C’s,’ Citizens), a federalist, economically liberal party founded in Catalonia in 2007, made the leap from regional politics to national politics, but its leader Albert Rivera must be disappointed that it failed to steal more voters from Rajoy.

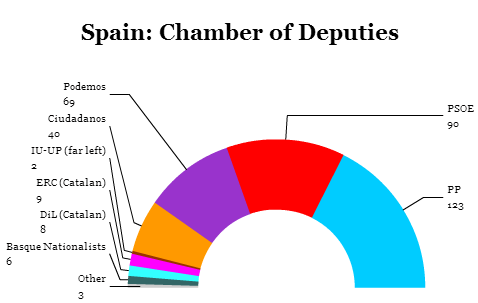

With another handful of seats going to various pro-independence Catalan parties, as well as Basque and Galician regional parties, the net result is that no one has enough seats in the 350-member Congreso de los Diputados (Congress of Deputies), the lower house of Spain’s legislature, the Cortes Generales (General Courts).

Notably, Rajoy maintained the PP’s majority, however reduced, in the far less powerful upper house, the Senado (Senate), which can be overruled on most matters (i.e., not ‘organic laws’ that deal with constitutional matters, civil rights and federalism) by majority vote of the Chamber of Deputies. Voters elected 208 senators on Sunday as well (an additional 58 senators are appointed by regional assemblies).

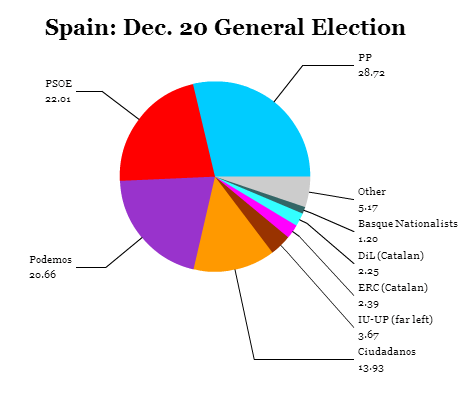

Two sets of statistics are worth considering.

First, the traditional major parties (the PP and PSOE) won just 50.7% of the vote in aggregate, compared to 83.8% in the 2008 election and 73.4% in the 2011 election. Obviously, that means Spain is entering a new era where coalition politics are more important. That’s not entirely unprecedented — when José María Aznar won 156 seats after the 1996 elections, he had to work with Catalan, Basque and Canarian nationalists to form a stable government. But the success of Podemos and Ciudadanos has transformed Spain’s politics from a two-party matter to a multiparty affair.

Secondly, among the four major parties to emerge from the 2015 election, it’s staggering just how evenly divided the Spanish left and right are. Together, the PP and Ciudadanos won 42.65% of the vote and the PSOE and Podemos won 42.67%. Spain’s electorate, in the broadest sense, delivered neither a mandate to a sharp left turn or a sharp right turn.

What Spain now faces is a difficult choice of among three different paths, all of which carry their own risks and challenges. Spain’s new young king, Felipe VI, will also take a more hands-on role in the coalition formation process than his father, Juan Carlos I, ever did. The good news for Spain is that the three options each mirror paths taken by three of its fellow European Union member-states in the last three years:

- Germany 2013: a ‘grand coalition’ between the two established parties;

- Portugal 2015: a fragile coalition government that brings together all of the parties and movements of the left; and

- Greece 2012: deadlocked coalition talks lead to fresh elections.

To the extent that Spain is entering a new coalition-based era of its parliamentary politics, a reshaped Spanish political landscape might transcend 20th century fractures and the transition to democracy that’s dominated Spanish political life for a half-century.

A German-style grand coalition

For now, the idea that the PP and the PSOE will join forces for a broad, pan-ideological coalition to steer Spain’s economy back to terra firma is a non-starter. Conceptually, the political divide is much deeper and more adversarial in Spain than in Germany or in Austria, where grand coalitions are the rule, not the exception. In the sole debate between Sánchez and Rajoy last weekend, Sánchez called Rajoy a liar and claimed that he was fundamentally indecent. Those kind of harsh personal attacks rarely precede national unity governments.

Increasingly, as Spain’s two-party system came under so much pressure in 2015, it was the PSOE that has resisted a grand coalition. Mindful, perhaps of the way that SYRIZA essentially decimated Greece’s longtime center-left party, PASOK, Sánchez knows that joining a unity coalition would be a political and ideological gift to Podemos, which could credibly pull more votes to displace the PSOE and become Spain’s new center-left standard-bearer. More broadly, a PP-PSOE coalition would also sharpen the lines between the traditional parties and the newcomers, a contrast that neither Rajoy nor Sánchez are excited about.

A Portuguese-style coalition of the left

In Portugal’s October elections, conservative prime minister Pedro Passos Coelho’s Social Democrats won the largest share of the vote, and he and his coalition moved quickly to attempt to assert his right to form a new government. Nevertheless, Socialist leader António Costa, a charismatic former Lisbon mayor, worked to build a majority, first, to deny Passos Coelho the right to govern and, secondly, to negotiate an unprecedented agreement among the various leftist parties of Portugal, including the anti-austerity Left Bloc and the even more radical Communists. Costa became prime minister on November 26.

For now, with the PSOE completely opposed to a grand coalition, and with Rajoy unable to gather a governing majority, Sánchez will have up to two months to fuse a similar left-wing coalition. As in Portugal, those efforts will take Herculean amounts of trust and goodwill, given that the PSOE and Podemos have very different policy views on economic matters, unemployment, corruption, electoral reform and devolution. (For example, the PSOE favors greater dialogue on federalism, while Podemos favors giving Catalonia an open vote on independence).

Moreover, even with the support of all of the PSOE and Podemos-affiliated deputies, the left would have just 159 seats, still 17 seats short of a majority. To reach the 176-member threshold, both the PSOE and Podemos would have to find a way to bring together a mix of Catalonia’s left-wing nationalists, Catalonia’s center-right nationalists, Basque nationalists or Spain’s small Communist faction. The result could be unwieldy and unstable, especially given the tensions over Catalan regional government.

Greek-style snap elections

If neither Rajoy nor Sánchez can build a government, Spanish voters will head back to the polls in the spring — in the same way that Greek’s hung parliament in May 2012 led to fresh elections a month later.

What might happen is anyone’s guess. There’s no guarantee that, in such a scenario, Rajoy and Sánchez would necessarily be leading their parties into a new vote because both parties have more appealing options (including Rajoy’s deputy Sáenz de Santamaría and the Socialist regional president of Andalusia, Susana Díaz). Furthermore, the December successes of the upstart Podemos and Ciudadanos might encourage more voters to depart from the traditional parties. Indeed, this is what happened in Greece, as PASOK’s voters increasingly flocked to SYRIZA.

In the meanwhile, Catalonia will almost certainly turn to the business of forming a new government, a process that has divided the broad pro-independence front of left-wing and right-wing parties that contested September’s regional elections on a platform of declaring independence within 18 months.