Until this summer, the conservative Hrvatska demokratska zajednica (HDZ, Croatian Democratic Union), fresh off a convincing victory in the December/January presidential election, seemed assured of its victory in Croatia’s parliamentary elections, enjoying a lead of more than 10% in most polls.![]()

Then something changed.

But it wasn’t that the HDZ was losing votes. Instead, leftist voters were abandoning their flirtation with a new left-wing party, Održivi razvoj Hrvatske (ORaH, Sustainable Development of Croatia), formed in October 2013 by former environmental minister Mirela Holy. At the height of its popularity in autumn 2014, ORaH was winning nearly 20% of the vote in polls, most of which came at the expense of the governing Socijaldemokratska partija Hrvatske (SDP, Social Democratic Party of Croatia).

Over the course of 2015, as ORaH’s support plummeted, those voters returned to the SDP and its governing allies that comprise Hrvatska raste (‘Croatia is Growing’) coalition, the largest member of which, by far, is the SDP. In Sunday’s election, ORaH’s vote share collapsed so completely that it failed to win a single seat in Croatia’s unicameral parliament, the Sabor.

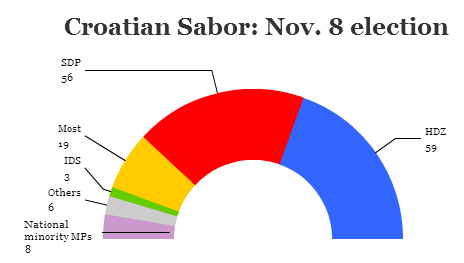

That, in part, explains why the SDP did so well on November 8. Nominally, the SDP won just 56 seats, while the HDZ won 59 seats. But three of the HDZ’s seats come from Croatian voters abroad, many of whom are ethnic Croats living in Bosnia and Herzegovina or elsewhere in the Balkans. Moreover, the SDP’s governing coalition can informally rely on a small regional party, the Istarski demokratski sabor (IDS, Istrian Democratic Assembly), which holds three seats, as well as eight additional legislators who represent national minorities, bringing the governing SDP to a more realistic base of 67 seats (just nine shy of the majority it would need for a new term in the 151-member Sabor).

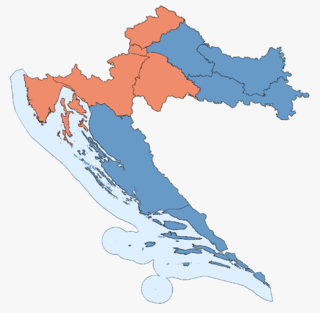

Not atypically, the Social Democratic Party performed best in the Croatian heartland and in Istria in the north and the west, while the Croatian Democratic Union did best along the Dalmatian coast stretching southward and in the far eastern Slavonia.

Ironically, it was the unexpected rise of a reform-minded centrist party, Most nezavisnih lista (Bridge of Independent Lists), that probably hurt the HDZ by drawing away reform-minded centrists. Barring the unlikely formation of a ‘grand coalition’ between the HDZ and the SDP, two parties with very different cultural and political traditions, it will be Most, a new party that formed only in 2012, and its 19-member caucus, that will now decide which of Croatia’s two dominant parties will form the next government.

Croatia’s prime minister Zoran Milanović, who leads the SDP, has struggled since his initial election in 2011 to boost the Croatian economy, which will post only tepid GDP growth this year following six consecutive years of contraction. High expectations gradually gave way to disappointment as his inexperienced government failed to enact the kind of reform program that his campaign promised.

Nevertheless, it was on Milanović’s watch that Croatia became a full member of the European Union. Despite his government’s actions to close off Croatia’s border with Serbia in September as refugees began flowing by the tens of thousands into the European Union from the Balkans, Milanović has generally espoused a welcoming and compassionate tone to refugees. Many of those migrants prefer to keep moving toward Austria or Germany than to stay in Croatia, a preference that Milanović hasn’t discouraged. Still, his demeanor has been more in line with German chancellor Angela Merkel than Hungarian prime minister Viktor Orbán.

The HDZ, though it wants to take a tougher line on migration, emphasized economic issues more than attacking refugees. With an unemployment rate of just over 16% and a youth unemployment rate of 43%, the European Union’s newest member has its third-highest joblessness rate (after Greece and Spain), even as Croatia’s public debt approaches 100% of GDP. Unlike some of its eastern and central European neighbors, Croatia hasn’t enacted the kind of economic liberalization that has become more common in countries like the Baltics and in Poland. Moreover, the HDZ’s campaign wrapped itself in the cloak of nationalism, leading an electoral coalition that it simply christened the Domoljubna koalicija (Patriotic Coalition). As in past campaigns, the HDZ whacked the SDP for its roots in the old Communist Party that controlled Yugoslavia in the 20th century.

Nevertheless, the HDZ is just as responsible as anyone else for the lack of meaningful reform. Since 1990, when Croatia declared its independence from Yugoslavia, the HDZ has governed for all but eight years, including the last four years under Milanović. It’s far more known for its corruption. Its former leader, former prime minister Ivo Sanader, was convicted on graft-related charges in 2012 and is currently serving an eight-year prison sentence related to bribes accepted from the CEO of a Hungarian oil company, the MOL Group, in its bid to acquire a majority stake in a Croatian oil company.

Though a coalition government, or an even more fragile minority government, might discourage reforms by making Croatia less stable, there’s reason to believe that Most‘s success could bring fresh momentum to the reform effort. Most, whose leader, the dashing 36-year old Božo Petrov won the mayoral election in the far southern city of Metković in 2013, has made it clear that he will condition his party’s support in exchange for acceptance of the Most reform agenda. Among its priorities are an improved and impartial judicial system, election law reform, reforms to streamline public services, and greater fiscal responsibility and transparency.

Given the choice, Milanović might represent the more promising path. The HDZ’s leader, Tomislav Karamarko, served as chief of cabinet in one of Croatia’s first post-independence governments, and he has served in the early 2000s as the director of Croatia’s intelligence service and in the late 2000s as Sanader’s interior minister. Something of a maverick throughout his political career, he ran the 2000 presidential campaign of Stjepan Mesić. He’s been the leader of the opposition since May 2012. But Karamarko isn’t the most charismatic or inspiring leader, unlike Kolinda Grabar-Kitarović, the former diplomat who won the Croatian presidency in January. Moreover, he has moved his party further to the right, including its strident support for a 2013 referendum measure that introduced a constitutional amendment banning same-sex marriage in Croatia. But that hasn’t necessarily convinced voters that Karamarko has purged the stench of corruption from the Sanader era.