Until this summer, the conservative Hrvatska demokratska zajednica (HDZ, Croatian Democratic Union), fresh off a convincing victory in the December/January presidential election, seemed assured of its victory in Croatia’s parliamentary elections, enjoying a lead of more than 10% in most polls.![]()

Then something changed.

But it wasn’t that the HDZ was losing votes. Instead, leftist voters were abandoning their flirtation with a new left-wing party, Održivi razvoj Hrvatske (ORaH, Sustainable Development of Croatia), formed in October 2013 by former environmental minister Mirela Holy. At the height of its popularity in autumn 2014, ORaH was winning nearly 20% of the vote in polls, most of which came at the expense of the governing Socijaldemokratska partija Hrvatske (SDP, Social Democratic Party of Croatia).

Over the course of 2015, as ORaH’s support plummeted, those voters returned to the SDP and its governing allies that comprise Hrvatska raste (‘Croatia is Growing’) coalition, the largest member of which, by far, is the SDP. In Sunday’s election, ORaH’s vote share collapsed so completely that it failed to win a single seat in Croatia’s unicameral parliament, the Sabor.

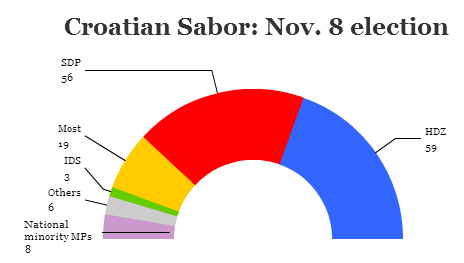

That, in part, explains why the SDP did so well on November 8. Nominally, the SDP won just 56 seats, while the HDZ won 59 seats. But three of the HDZ’s seats come from Croatian voters abroad, many of whom are ethnic Croats living in Bosnia and Herzegovina or elsewhere in the Balkans. Moreover, the SDP’s governing coalition can informally rely on a small regional party, the Istarski demokratski sabor (IDS, Istrian Democratic Assembly), which holds three seats, as well as eight additional legislators who represent national minorities, bringing the governing SDP to a more realistic base of 67 seats (just nine shy of the majority it would need for a new term in the 151-member Sabor).

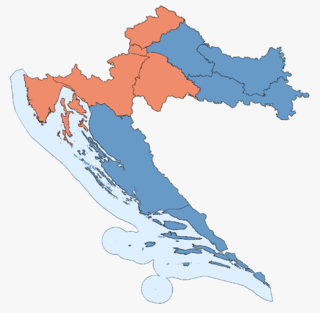

Not atypically, the Social Democratic Party performed best in the Croatian heartland and in Istria in the north and the west, while the Croatian Democratic Union did best along the Dalmatian coast stretching southward and in the far eastern Slavonia.

Ironically, it was the unexpected rise of a reform-minded centrist party, Most nezavisnih lista (Bridge of Independent Lists), that probably hurt the HDZ by drawing away reform-minded centrists. Barring the unlikely formation of a ‘grand coalition’ between the HDZ and the SDP, two parties with very different cultural and political traditions, it will be Most, a new party that formed only in 2012, and its 19-member caucus, that will now decide which of Croatia’s two dominant parties will form the next government. Continue reading Reform-minded ‘MOST’ party set to play kingmaker in Croatia