In the wee foggy hours of January 21, 1994, a speeding Mercedes crashed on the highway en route to Damascus International Airport.![]()

Its driver was 31-year-old Bassel al-Assad, the eldest son of Syria’s president, Hafez al-Assad, and he died instantly. His death scrambled what had been a long-planned succession for Syria’s aging ruler. From an early age, it had always been clear that Hafez was grooming Bassel — by far, the most popular and charismatic of Hafez’s sons — to succeed him.

His death forced Hafez to switch plans, despite more than a decade of work preparing Syria for Bassel’s eventual ascension and preparing Bassel to one day rule Syria with the same grip as his father had.

Bashar al-Assad, Bassel’s younger brother, was immediately recalled from London, where he had lived for two years engaged in post-graduate studies as an ophthalmologist. For the next six years, until his father’s death, Bashar underwent a transformation to prepare to take the reins of the family business.

Like Che Guevara in Cuba, Bassel’s face routinely greets everyday Syrians alongside Bashar and Hafez. Or at least it does in what little Syrian territory remains dominated by the Assad regime these days. As Syria’s hell continues through its fourth year, many Syrians must wonder whether their lives would have turned out differently under the other Assad son.

So as Russian fighter jets land at Bassel al-Assad airport in an escalating effort this month to boost the struggling Assad regime, it’s tantalizing to wonder what might have happened if the Latakia airport’s namesake had survived.

As Roula Khalaf wrote for The Financial Times in 2012, no one ever expected Bashar to one day become Syria’s president — least of all, probably, Bashar himself:

“Growing up, Bashar was overshadowed by Bassel,” says Ayman Abdelnour, a former adviser who got to know Assad during his university years. “That seemed to be a complex – he didn’t have the charisma of Bassel, who was sporty, was liked by girls and was the head of the Syrian Computer Society.” Bashar was “shy; he used to speak softly, with a low voice. He never asked about institutions or government affairs.” Assad was also close to his mother, Anisa Makhlouf, whose family played a central part in the regime. “A mama’s boy more than a papa’s boy,” is how one western politician describes the president.

In 2000, ready or not, Bashar assumed the presidency at age 35.

Even before Syria’s civil war began in 2011, the eye doctor-turned-strongman showed signs of weakness. There was an initial period of political freedom in the first year of his regime — though the period became known as the ‘Damascus Spring,’ the term now rankles with irony, and the thaw on political dissent clearly ended by 2002. In the wake of the US military’s overthrow of Iraqi president Saddam Hussein, the remaining Ba’athist regime in the Middle East, Assad spent much of 2003 and 2004 worried that neoconservatives might attack him next (a fear that was not entirely unfounded).

Bashar’s biggest miscalculation came in Lebanon, where nearly everyone believes Syrian forces assassinated former prime minister Rafic Hariri in 2005, a galvanizing moment for Lebanon that generated backlash among Lebanese of all backgrounds and religions. Ultimately, the furor over Hariri’s shooting forced Bashar to withdraw the Syrian troops that had occupied much of the country since Lebanon’s own civil war began in 1976.

Isolated, a middling diplomat and a failed reformer, Bashar’s miscalculations were evident — long before he allowed a civic movement to turn into a civil war, long before a principled, secular Sunni opposition morphed into a barbaric jihadist caliphate and long before a brutal regime turned to sarin and other chemical weapons.

It’s not as if the Assad family ever truly had it easy.

Hafez, a member of the Alawite tribe, a sect of Shiites in a Sunni-majority Arab country, took power during the 1963 coup, which brought Syria’s branch of the once-powerful Ba’ath Party to rule — exactly one year after Bassel was born and two years before Bashar’s birth.

Over time, however, Hafez’s strength grew and by 1970, he had engineered a coup to overthrow his fellow Alawite Salah Jadid (he threw Jadid in prison for the next 23 years until Jadid died). In the 1970s, he faced the rise of Yasser Arafat’s Palestinian Liberation Organization, a group that caused more trouble in 1970s Jordan and Lebanon than in Israel. An Islamist uprising in the late 1970s and early 1980s ended with the horrific Hama massacre that killed up to 40,000 Syrians, many sympathetic to the Muslim Brotherhood’s attempt to overthrow the Ba’athist regime.

After a heart attack in 1983, Hafez’s own brother tried to overthrow him. Though Hafez retained power, and he would live on for another 17 years, he began his efforts to groom Bassel for the Syrian presidency soon thereafter. Within a decade, Bassel’s personality cult was stronger than Hafez’s, and the father even ran under the slogan of ‘Abu Bassel,’ the father of Bassel, in the uncontested 1991 presidential contest.

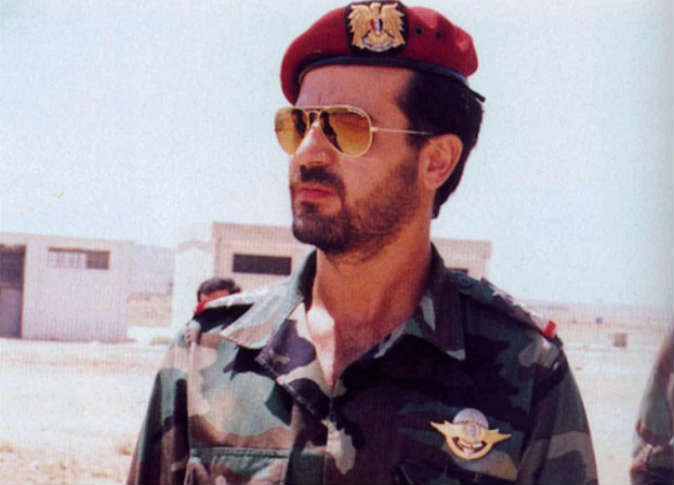

Much of his young son’s popularity was genuine. Bassel was a swaggering athlete with sex appeal, above all in a part of the world with especially geriatric leadership, in the 1980s as much as today. At the time of his death, he was a highly accomplished equestrian, a decorated commander in the Republican Guard, the presidential security force, and the head of the Syrian Computer Society in an era when Syrian technology was still decades behind American, Japanese or Western European technology. He cultivated strong relationships with leaders across the Middle East, most of all in Lebanon. As Robert Fisk wrote for The Independent after Bassel’s death, he also had a reputation for honesty, showing at least some initial interest in rooting out the most corrupt elements of the Syrian regime:

Several military road-blocks manned by his soldiers were set up near the Syrian frontier with Lebanon – ‘Basil checkpoints’, they were called – to hunt for smugglers. The message was obvious: unlike other, less trustworthy Syrian luminaries, Basil could be trusted.

So what if Bassel had survived that 1994 automobile crash?

Of course, no one knows.

Over the past four years, statues of Bassel were torn down along with statues of other family members. The Arab Spring protests of 2011 finished off far more experienced rulers than Bashar — Egypt’s Hosni Mubarak, Tunisia’s Zine El Abidine Ben Ali, Libya’s Muammar Gaddafi, all of whom would have had decades of experience more than Bassel too.

But Bassel, with over 15 years of hands-on preparation, would have come to power with much more experience and legitimacy than Bashar. If he had wanted to roll out his own Damascus Spring, he would have been in a much stronger position to do so. He certainly would have been in a stronger position to enact the kind of economic reforms that Bashar attempted, and which fell flat throughout the 2000s.

It’s also hard to imagine Bassel making the same mistakes in Lebanon back in 2005. It’s also hard to imagine that Hezbollah, the Iran-backed Shiite militia in Lebanon, would have waited so long to intervene in favor of the Assad regime if there had still been a Syrian military presence in Lebanon at the start of the civil war. Without Hariri’s assassination, Syria’s presence in Lebanon might have otherwise continued for years. (To be fair, a Bassel-led Syria might have done much more to drag Lebanon itself into the civil war, on either side).

Though Bashar’s relations with Turkey and its long-serving leader Recep Tayyip Erdoğan improved substantially over the course of the 2000s, the civil war changed all of that, and Bashar and Erdoğan have yet to cooperate in any concerted effort to eradicate Islamic State/ISIS, which now controls nearly the eastern two-thirds of Syria, including along its border with Turkey. Might Bassel have done better? He hardly could have done worse.

There’s also the other alternative.

As brutal as Syria’s war has been, it might have been worse under a more cruel, iron-fisted leader willing to engage in far more flagrant human rights violations and, incredible as it may seem, even greater numbers of casualties, refugees and internally displaced Syrians. It’s also entirely possible that a more tyrannical response would have more forcefully quelled the dissent (just as Hafez extinguished the Muslim Brotherhood-led revolt in the early 1980s), thereby avoiding a drawn-out and utterly crippling descent into misery and larger casualties. While it’s a ghoulish arithmetic, Bassel might have at least left the country in a better position to combat Islamic State’s cross-border jihadists.

Whatever Syria’s future holds, it certainly wasn’t the future that Hafez was trying to craft, and that he spent half his tenure attempting to guarantee for his family or his country.

Technology was not behind