A candidacy that struggled to win enough parliamentary nominations to run, and a candidate personally ambivalent about running — unsure he was up to the campaign, let along up to the job.![]()

A nomination supported by MPs who thought the far left should have a ‘voice’ in a campaign that, like in the past, would show just how anemic Labour’s far left is — and as weak as it would always be.

A surge that everyone, from former prime minister Tony Blair on down, believed would subside as the fevers of summer cooled and Labour’s electorate focused on a leader who might deliver the party to a victory.

A frontrunner who, despite a three-decade legacy of statements and positions that might otherwise doom another candidate, somehow swatted aside the taunts of Labour and Conservative enemies alike and, in his quiet, relentlessly focused and humorless manner, kept his attention on policy, not in responding to negative attacks or engendering gauzy feel-good connections via YouTube clips or on the rope line. What you see is what you get.

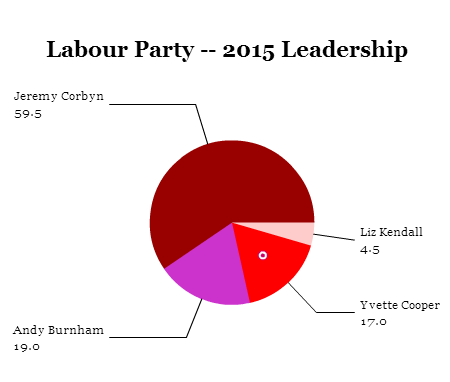

Today, Jeremy Corbyn becomes the duly-elected leader of the Labour Party, and he easily won with first preferences, far outpacing his nearest competition in shadow home secretary Yvette Cooper and shadow health secretary Andy Burnham.

Corbyn will also become a leader who now faces an outright mutiny from some of the party’s most important policy experts and rising stars. Despite his staggering win, which scrambles the very nature of postwar British politics, which created a revolution within Labour and which perhaps can begin a new epoch of British politics, the 66-year-old Corbyn must now wage a fight to consolidate his hold on the mechanisms of the party — from mollifying critics in the parliamentary caucus to reimaging the levers of policy review.

After a summer of Corbynmania, the late surge of shadow home secretary, Yvette Cooper, newly impassioned about economic policy and Syrian refugees, wasn’t enough to deny the leadership to an unlikely hero of the far left, a man who would make Tony Benn himself seem moderate and accommodating by contrast.

But as Corbyn takes the reins as the leader of Her Majesty’s Opposition, he should take to heart the hard-won lessons of those who held the office before him — stretching back to 1983, when Neil Kinnock first won the leadership.

Including Kinnock, there are four living former leaders of the Labour Party. Each of them, and their records, hold wise counsel for Corbyn as he attempts to consolidate power within Labour so that he’ll have a chance, in the 2020 election, to become prime minister in his own right.

Neil Kinnock: 1983-1992

Neil Kinnock: 1983-1992

Labour is the party of continental cosmopolitanism

Before Tony Blair was the image of a new, modern version of Labour, it was Neil Kinnock, who surged at the end of a 1987 campaign that had been Margaret Thatcher’s election to lose and who fell just short in the 1992 election that, in turn, had been Kinnock’s to lose.

If the British electorate (and history) have been unkind to Kinnock, his legacy lives on in Labour’s enthusiasm for the European project. Unlike his predecessors Michael Foot and prime minister Harold Wilson, Kinnock’s devotion to the European Union was unyielding. Kinnock’s son, Stephen, elected as an MP from a Welsh constituency in the May 2015 general election, is married to former Danish prime minister Helle Thorning-Schmidt, Denmark’s first female prime minister. Like former Liberal Democrat leader Nick Clegg, who is married to a Spanish national, European integration was and remains a personal matter for Kinnock.

Though he never made it to 10 Downing Street, and though his support for Ed Miliband and (now) Andy Burnham may have been misplaced, Kinnock reoriented Labour into the pro-European party that it is today.

Corbyn has been cagey throughout the leadership campaign about the United Kingdom’s continued membership in the European Union. For now, that’s perhaps a good strategy — for a leader who wants to woo back supporters of the United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP) or who wants to strike a hard bargain with prime minister David Cameron over the UK’s social policy obligations in a European superstate that, as Corbyn believes, tilts too far to the neoliberal.

But a British vote to leave the European Union would be disastrous — and not just for the City. It would amount to a unilateral act of economic autarky and it would annoy the United States (no matter who wins the 2016 presidential election), which counts on Britain as its chief voice on European policy. Outside the European Union, the United Kingdom would still probably be forced to accept EU decision without the ability to shape those decisions. All the more reason for Corbyn to embrace the European project — and soon.

Tony Blair: 1994-2007

Tony Blair: 1994-2007

Showmanship matters, especially winning over English voters.

Blair today is the most successful living Labour leader, leading the party to victory after 18 long years in the wilderness to three consecutive general election victories. Corbynites, however, point to the fact that Labour’s vote share fell by nearly 2 million in the 2005 election, Blair’s last effort. As if the Iraq War disaster wasn’t enough, Blair struggles now with the sense that his governments were too lenient on the City through his own determination to amass personal wealth in the past decade since leaving office. So it’s not surprising that Blair’s knock to Corbyn supporters, saying that they need a ‘heart transplant’ or that they subscribe to ‘Alice-in-wonderland’ politics were tonedeaf.

It was always certain that the ‘New Labour’ moment would pass, rooted as it was in the ‘third way’ triangulation of US president Bill Clinton and German chancellor Gerhard Schröder.

For all his sins among the Labour purists, however, Blair’s most excusable one was courting Rupert Murdoch, whose Sun famously took credit for dooming Kinnoch’s razor-thin defeat in 1992.

If Corbyn and his merry band survive their first year in power, and if Corbyn survives the 2016 regional elections in Scotland and the planned 2017 referendum on the United Kingdom’s membership in the European Union, he will have won at least some begrudging respect. But to become a truly credible prime minister-in-waiting, Corbyn will have to reassure the gatekeepers of ‘respectable opinion’ — who can, in turn, reassure the voters across Tory-dominated southwestern England that also elected Blair. So much of this is steeped in image, and not in policy fundamentals — recall that, even as the supposedly too-leftist-to-trust ‘red Ed’ Miliband lost the 2015 election, he had already decided not to fight the election on Cameron-Osborne austerity, tacitly accepting the Tory premise that Labour overspent in the Blair-Brown years.

Gordon Brown: 2007-2010

Gordon Brown: 2007-2010

The best policies are not always the most popular.

Brown, who belatedly endorsed Cooper in the leadership race, delivered a speech about the history of the Labour Party earlier in the summer, and he made the case — with passion and sincerity — that Labour can only make a difference if it has the ability to gain power. It wasn’t unlike his earnest pleas with his native Scotland to remain in the United Kingdom in 2014 that were well-received and, indeed, more effective than anything plotted by the ‘Better Together’ campaign hatched by Brown’s former chancellor Alistair Darling or Cameron. (For what it’s worth, Corbyn’s uncompromisingly leftist view could wrest back Labour supporters from the clutches of Scottish first minister Nicola Sturgeon and the pro-independence Scottish National Party).

Brown, from the earliest days as chancellor in the late 1990s to the final days of his premiership, often embraced policy positions that put him at odds with his own party or the public in general. When Labour swept to power in 1997, Blair and his cadres, and even europhile Tories like Kenneth Clarke, believed that the United Kingdom’s future lay in joining the eurozone. Brown’s restrictive ‘five tests’ made it nearly impossible for Blair to steamroll the country into the single currency, a decision that in retrospect seems especially wise for the British economy.

In 2008 and 2009, Brown showed no qualms in unleashing the fiscal spigot to boost aggregate demand — nor did he waste any time nationalizing Northern Rock. His aggressive stand on the financial crisis bolstered governments across Europe and even influenced the nascent government of US president Barack Obama. Though Cameron and chancellor George Osborne won the 2015 election by slurring the Labour record on spending, Brown’s record in particular has much to recommend it, even if Brown himself wasn’t the most effective prime minister.

The lesson here for Corbyn is that he need not follow the media zeitgeist in setting policy. Though it’s hard to see how something like ‘people’s quantitative easing’ could ever work, there are strong arguments that Trident is a relic of the Cold War and an unnecessary expense for the British treasury. At a time when class distinctions are stronger than ever, Corbyn may be right that it’s time for a correction to the Thatcher-era spirit of laissez-faire with respect to the National Health Service, Britain’s railways, student tuition and fees and to the budget cuts of the Cameron government, too.

Ed Miliband: 2010-2015

Ed Miliband: 2010-2015

No one praises your ability to unite until everyone’s divided.

Over the past five years, nobody realized just how divided Labour had become. That’s a testament to Miliband’s leadership in bridging the chasm between the New Labour ‘modernizers’ and Old Labour socialists. The divide that now exists on the British left makes clear just how petty, unprofessional and insignificant the dramatic fights between ‘Blairite’ and ‘Brownite’ factions actually were. Though Miliband faced his own demons as leader, including a couple of serious leadership scares and the ignominy of challenging and defeating his own brother, his chief talent — as now seems so very clear in retrospect — was bridging the Blairite right wing with left-wing union members.

So the first step for a successful Corbyn will be to make it easier for Labour’s centrists, still over-represented in the current parliamentary caucus, to support him. In this regard, the triumph of electric newcomer Sadiq Khan on Friday over Blairite stalwart Tessa Jowell in the contest to determine Labour’s candidate for London mayor may convince moderates that Corbyn represents a trend much larger than himself.

Some of Labour’s ‘big beasts’ will step aside, certainly, unwilling or unable to defend Corbyn’s near-socialist agenda. But Corbyn-as-leader (and not Corbyn-as-backbench-rebel) will pick and choose his battles. To that end, he might yet convince rising stars like Chuka Umunna and Dan Jarvis to take positions in his shadow cabinet. Hilary Benn, if he continues as shadow foreign secretary, could provide immediate credibility. As could the erstwhile Alan Johnson, the only member of the New Labour high command (he served as Brown’s home secretary) with any true regard among the Labour rank-and-file. Cooper, though she has said she won’t serve in his cabinet, would be a splendid shadow home secretary under any leader, and the pressure she applied to Cameron and home secretary Theresa May on admitting more Syrian refugees shows just how indispensable she is to British policymaking, even in the opposition.

Even Miliband himself, a talented former leader, could play a role in soothing the wounds of the most caustic leadership battle in decades. Notwithstanding Corbyn’s shadow cabinet, he must show that he is willing to compromise in a way that he hasn’t been forced to do on the backbenches.

Brian,I’m not sure that he is a Muslim, although he did spend many years being indoctrinated. Actually, I’m not sure he is anything more that a great orator that as Chris Christie so ably put it, #2;can&88217;t find the light switch for leadership!”