HAVANA — On my first evening in Cuba , my bar ran out of mojitos, as fitting metaphor as any for nearly a week in the Cuban capital.![]()

Sure, it wasn’t the bar at Havana’s Hotel Nacional, but it was still a reasonably tourist-oriented cantina with a Chilean theme hugging the Malecón, the popular avenue that runs along the sea. For the record, the restaurant also ran out of shrimp and tostones (the fried plantain chips I’ve always thought taste like fried discs of baking powder with a hint of banana).

I’ve been to poorer countries, but it’s hard to think of a place that’s more broken. The keys, the doors, the cars, the buildings, the stores, the distribution channels and yes, even the much-vaunted health care system. The idea that the United States and its legions of consumers and tourists will transform the country virtually overnight is incredibly fanciful.

For many Americans, there’s an element of romance to seeing old cars from the 1950s and the faded mojitos-and-daiquiris glamour of what was once a Caribbean playground. There’s also an electricity that comes from a place that’s so close geographically but so distant ideologically, politically, economically and culturally. One comparison that springs to mind is the 12-mile distance between Jerusalem and Ramallah.

Another comparison is Korea — for all the easy talk about reconciliation between the United States and Cuba, the distances between the two countries are nearly as stark as those today between North Korea and South Korea. That isn’t quite so surprising because Fidel Castro came to power only six years after the 1953 armistice than ended the Korean War in quasi-permanent stalemate. Today, there is a Cuban-American culture that is as distinct from Cuban culture as Sicilian-American culture is from life in modern Palermo. Celia Cruz and Cafe Versailles belong to the former, Osmani García and the inventive home-grown paladar restaurants belong to the latter.

Miami is now Cuba’s “second city,” not Santiago, and there’s a strong case that Miami, not Havana, is the cultural capital of what it means to be Cuban.

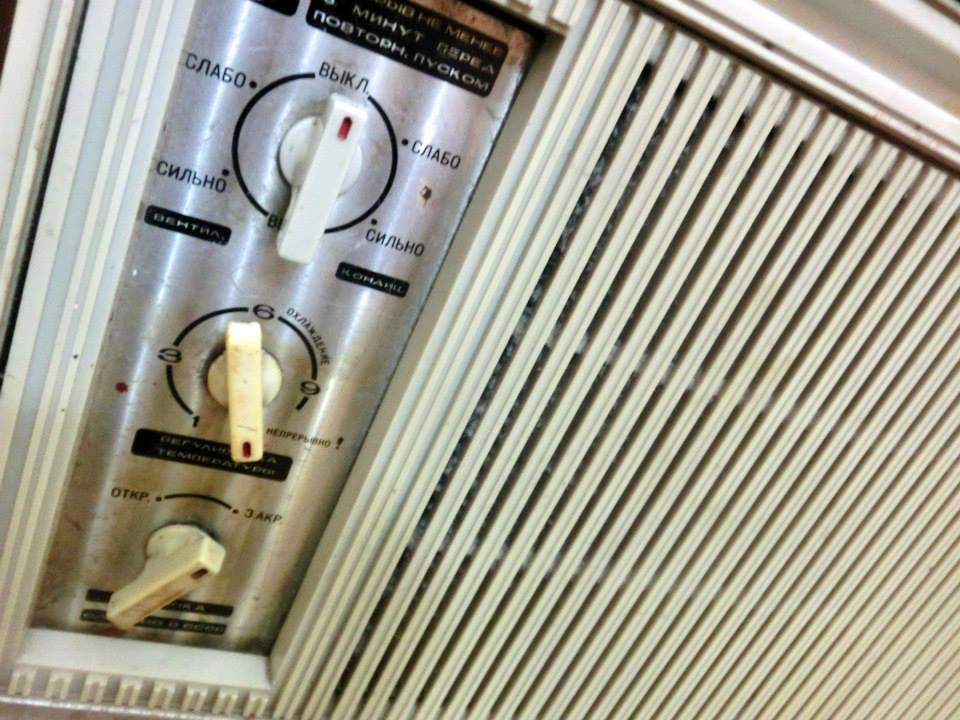

On the ground in Havana, however, that wears off quickly. But no one ever says, “I want to see all the broken-down 1970s-era Soviet Ladas before they’re gone.” Or the other crumbling remnants of Cuba’s three decades as a Soviet satellite, including the surprisingly robust air conditioner in my casa particular.

Parts of Central Havana are so crumbling that they resembled the bombed-out ruins of Panama City’s Casco Viejo, which sustained the most damage in the U.S. military action there in 1989 to capture strongman Manuel Noriega. Except no one ever bombed Havana — it’s the product of socialist neglect, exacerbated by the stubborn effects of the U.S. embargo (though, it’s fair to say, there’s no rush of European, Chinese or Latin American capital rushing into Cuban infrastructure).

That neglect extends to Havana’s numerous government-run stores. Though you can, in fact, find great food in Havana, you won’t find it in any grocery store — in this one in Havana Vieja, rum accounted for nearly one-third of the ‘viveres.’

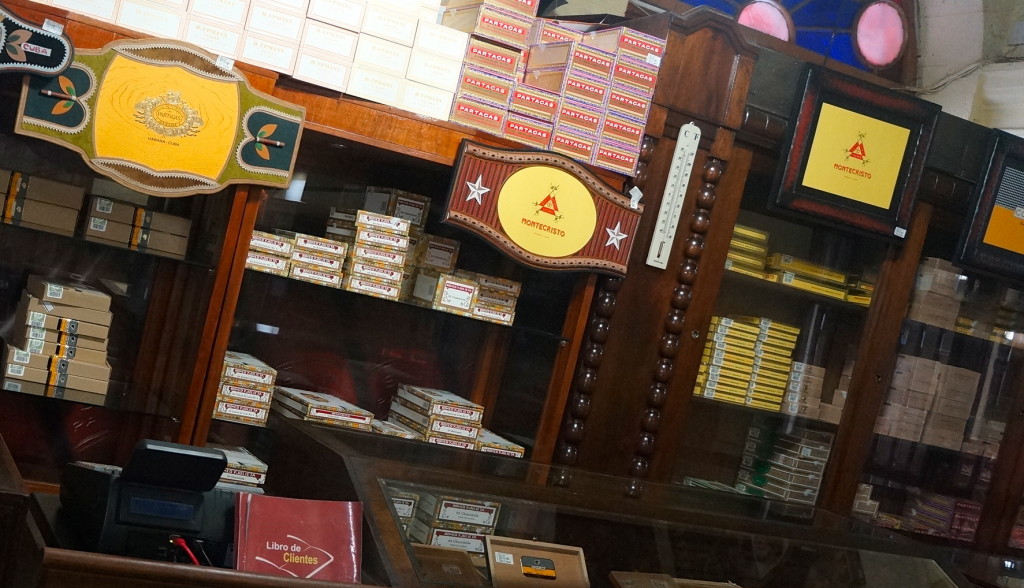

For the record, the rum isn’t all it’s cracked up to be. Havana Club’s ubiquitous seven-year aged dark rum is spicy, but it isn’t as smooth as equivalent Guatemalan, Nicaraguan or even Venezuelan rums. Likewise, cigar aficionados have, for years, argued that the lack of reliable quality controls in the Cuban tobacco industry mean that the country’s cigars are no longer the world’s best, though the Cuban terroir is as well-suited for tobacco as anywhere else in the world. Improvements in Nicaraguan and Dominican cigar-making, too, have leveled the playing field. When and if the United States lifts its embargo, and the novelty wears off, U.S. consumers may find that the appeal of Cuban cigars and rum had more to do with the fact that they were forbidden.

Bread shops, which dot the city, were plentiful and their goods were cheap, but it’s not exactly reminiscent of a Parisian boulangerie.

For a country that sees tourism as its future cash cow, the restaurant scene leaves much to be desired (though that may be different in the resort areas of Varadero, far removed from the everyday experience of Cuban life). You’ll find, in addition to the tostones, rice and black beans that comprise so much of the Cuban comida criolla, plenty of seafood, including lobster, shrimp, fresh fish and octopus. Good luck finding any that isn’t overcooked, over-buttered or over-garlicked. The best food of my brief visit came at a paladar — a small individually-run restaurant in a Cuban home — in the leafier neighborhood of Vedado. Even then, I was the only guest that afternoon and finding the place was an adventure in itself, nestled on the 11th story of a nondescript walk-up.

The view was superb, because it reflected the oceanfront and a part of Havana that isn’t completely in ruins. The best dish was the ‘fried chickpeas,’ an old Cuban comfort food that’s more like a stew of garbanzo beans, tomatoes, onions and peppers flavored with curry and ham.

Though Coppelia, the city’s strange, spidery, concrete amusement park of an ice cream parlor, is well-known, the lines of Cubans gathering there on warm summer days are due less to its innate popularity or quality than to the fact that, as far as I could tell, it’s the only ice cream store of its kind in the city.

The neglect also extends to public memorials.

Here, a forgotten and forlorn monument to Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. has become a sad tribute to “D MARTIN THE KING J.”

It’s a particularly cruel twist for Afro-Cubans, who have suffered disproportionately in the Castro era. Despite claims that the Revolution eradicated racism, the Revolution’s leaders were predominantly white, middle-class Cubans and they quickly dismantled the sociedades de color that existed within Afro-Cuban society and largely discouraged the santería religious tradition. Today, Afro-Cubans receive fewer remittances from the chiefly white Cuban-Americans who emigrated in the last half-century, exacerbating the racial disparity in Cuban income inequality. So I found displays like David Hammons’s mid-century ‘African-American flag’ — shown below hanging from Cuba’s national art gallery — to be particularly hollow.

For all the talk of LGBT rights, with the much-heralded work of Raúl’s daughter, Mariela Castro, in fighting for the humane treatment of Cuba’s gays and lesbians, many of whom were sent off to labor prison camps with other perceived enemies of the Revolution in the late 1960s and, especially during the first half of the 1970s, a time known as the Quinquenio Gris (the ‘grey five-year period’). A night out at Humboldt 52, one of the city’s new (and few) gay bars, was not entirely unlike a night out in other Latin American cities, but it lacks the same vibrancy of a place like Mexico City or even Lima. It certainly holds the record for the number of times I was propositioned for a sexual transaction in a single night (three).

Havana, in pre-revolutionary days, was also home to one of Latin America’s most populous Chinese communities, and all the remnants of the Barrio Chino remain, even though most of the Chinese-Cubans left when Castro came to power.

I was fairly surprised at the lack of revolutionary propaganda, at least outside the Plaza de la Revolución, which outdid even Beijing’s Tiananmen Square with its aura of sheer creepiness. Che Guevara’s simple outline, a familiar sight, is actually affixed to the main building housing the Ministry of the Interior, Cuba’s internal police force that has been responsible for so much misery in the authoritarian country.

While there’s certainly a personality cult surrounding Che Guevara (or at least the Che brand), the strongest presence in Havana is still José Martí, the intellectual and writer who gave his life in 1895 for the cause of Cuba’s independence.

That doesn’t mean you can’t feel the Revolution’s influence, and though there were few posters of Fidel or Raúl Castro, there were a significant number of posters lionizing Hugo Chávez and the socialist Venezuela that, for the past decade, has been Cuba’s chief benefactor.

It was certainly stronger than any buzz over the beatification of Salvadoran priest Óscar Romero, murdered by a right-wing death squad in 1980 in the midst of El Salvador’s civil war. Attendance at a mass commemorating his beatification last Sunday afternoon in Havana’s cathedral was surprisingly sparse.

When Fidel Castro dies, he’ll be mentioned in the same breath as Nelson Mandela or other heroes of the 20th century for what 1959 represents, not only to Cubans, but to Latin America. Though US secretary of state John Kerry may have declared the end of the Monroe Doctrine quietly in 2013, it’s really Castro who won sovereignty for Latin America.

But if Castro is a hero for 1959, he’ll also be remembered with far less praise for every year that followed 1959. Given the heavy U.S. influence in Cuba from the end of the Spanish-American War up to the early days of the Cuban revolution, it’s no overstatement to say that Cuba won its independence only in 1959. Even if many Cubans aren’t enamored of Castro in the 57th year of its crepuscular Revolution, they’re still fiercely nationalist.

But if Castro is a hero for 1959, he’ll also be remembered with far less praise for every year that followed 1959. Given the heavy U.S. influence in Cuba from the end of the Spanish-American War up to the early days of the Cuban revolution, it’s no overstatement to say that Cuba won its independence only in 1959. Even if many Cubans aren’t enamored of Castro in the 57th year of its crepuscular Revolution, they’re still fiercely nationalist.

Posters, still imploring Cubans to participate in the April 19 municipal elections, are a stark reminder that Cuban-style democracy still means a one-party state, with all loyalty flowing to the Partido Comunista de Cuba (PCC, Cuban Communist Party), and that doesn’t seem set to change with either normalized U.S. relations or with the planned 2018 transition from Raúl Castro to a new president, and despite the fact that two dissident candidates, Hildebrando Chaviano and Yuniel López, were permitted to stand (however unsuccessfully) for election in April.

That’s why, in so many ways, it feels much more like post-independence countries in sub-Saharan Africa that won their own independence at the same time and struggled in similar ways to create institutions under the Cold War aegis. As in Cuba, revolutionary leaders like Robert Mugabe and Ahmed Sékou Touré who proved so successful at liberation turned out to be disastrous at the task of government.

By far, the most lively part of the city remains the Malecón, where it feels like the entire population (or at least its youth) gather on weekend nights — and a fairly good share on weekday nights as well. A cynic might say that’s because it’s as far away as you can get from the crumbling mess that characterizes much of the rest of the city.

With the Havana Biennial taking place this month, the Malecón is filled with public art, including the outline of a giant Facebook “Like” icon that I found particularly subversive in a country where Internet access is restricted to a handful of government-run hotels, universities and other institutions.

At a price of $10 per hour, it’s also prohibitively expensive in a country where the salary for public workers is around $20 per hour. Using one of those expensive connections, it was already impossible to load the new website launched by Yoani Sánchez, Cuba’s well-known blogger, 14yMedio, suggesting that the Castro regime is already perfecting restrictions on the free flow of online information.

By and large, that’s forced Cubans to become extraordinary hustlers and entrepreneurs in everyday life. That’s especially true in light of the complex currency controls. Though Raúl Castro’s administration pledges to dismantle it, Cuba has two currencies — the peso or the ‘moneda nacional‘ that most Cubans use for everyday purchases and the convertible peso (or ‘CUC‘). It’s a great racket for the Cuban government.

Tourists come to the country with hard currency, like euros or Canadian dollars or U.S. dollars. They exchange that hard currency at CADECA, the state-run currency broker, for CUCs, which are pegged to a nominal 1:1 rate with the U.S. dollar (despite the fact that U.S. dollars are subject to a churlish 10% penalty fee from the Cuban government). That, in turn, has created a bifurcated society of Cubans with access to CUCs and those with access to pesos (which are worth just 1/25th of one CUC).

Confused yet? With the impending plan to merge the two currencies, it could create even more pandemonium because no one knows how exactly the Cuban government will pull it off without wiping out the value of CUCs, plunging the country’s fragile entrepreneurial class into economic crisis. Many of Cuba’s Millennials grew up during what Castro euphemistically called the ‘Special Period in a Time of Peace’ — near-famine conditions between 1991 and 1994 when the Soviet Union, and its subsidies to Cuba, collapsed.

Above all, the sense that I got from five days of talking to activists, students, young Cubans and other folks in Havana was not a country ‘on the brink’ of becoming a Caribbean Singapore with Netflix and Apple in every house and a thriving, efficient business climate for foreign investment. There’s a keen sense that a new chapter is opening for Cuba but, despite the optimistic headlines in U.S. newspapers since last December, it’s not yet clear what that future will mean for everyday Cuban citizens.

Above all, the sense that I got from five days of talking to activists, students, young Cubans and other folks in Havana was not a country ‘on the brink’ of becoming a Caribbean Singapore with Netflix and Apple in every house and a thriving, efficient business climate for foreign investment. There’s a keen sense that a new chapter is opening for Cuba but, despite the optimistic headlines in U.S. newspapers since last December, it’s not yet clear what that future will mean for everyday Cuban citizens.