It’s easy to forget about the northeastern corner of South America, collectively known as ‘The Guianas,’ which includes two countries (Guyana and Suriname), a French overseas holding (French Guiana) and, sometimes, the sparsely populated eastern Guyana region of Venezuela and Amapá state in northeastern Brazil.![]()

Those two sovereign countries, Guyana and Suriname, formerly British and Dutch colonies, respectively, are home to just over 1.3 million people. French Guiana, an overseas department of France, and one of the Western Hemisphere’s last vestiges of colonialism, is home to just another 250,000 people.

Even by the standards of Latin America, which is arguably underpopulated (especially in contrast to China, India and other parts of southeastern Asia), the Guianas are some of the least population-dense places on earth. Guyana, home to just 750,000 people, has a population density of around 9.5 per square mile. To put that into perspective, it compares to densities of around 37 for Argentina, 62 for Brazil, 85 for the United States and 158 for Mexico.

Earlier this year, however, Exxon Mobil claimed it discovered offshore oil deposits that could boost the country’s economy, though attempts to extract the oil could draw Venezuelan ire. Nevertheless, the region remains relatively underdeveloped and Guyana is one of the hemisphere’s poorest countries, despite gold and bauxite deposits and steady rice and sugar production. More than 50% of its native population has emigrated — only Nicaragua and Haiti have lower per-capita GDPs.

That’s part of the reason that former army general David Granger (pictured above) led a multi-ethnic coalition to power in elections on May 11.

It’s the first transition of power since 1992, when the People’s Progressive Party (PPP) dominated the country’s post-socialist turn to democratic politics. PPP officials, including former president Donald Ramotar, still refuse to concede their narrow defeat, even as Granger was sworn in over the weekend as Guyana’s new president. Traditionally, the PPP has depended on votes from the ethnic Indian community in Guyana. While Granger’s coalition won the traditional support of the Afro-Guyanese community, the multi-ethnic patina of the coalition bolstered his claim to destroy race-based politics in the oft-forgotten country.

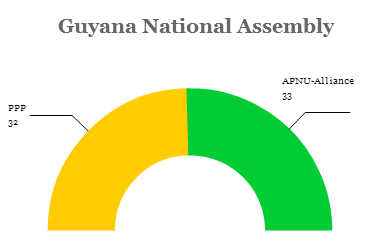

Ramotar called snap elections earlier this year after facing a vote of no confidence in the 65-member National Assembly, proroguing the parliament last November. That effectively postponed the elections until May and prevented the no-confidence vote supported by opposition politicians angry with the PPP-led executive’s spending. The president represents one of two branches of the parliament, and the role is elected indirectly by the National Assembly.

Indo-Guyanese amount to around 43% of the population, while Afro-Guyanese number around 30%, with native and mixed populations constituting the rest of the country’s ethnic makeup.

The 32 seats that the PPP won on May 11 is exactly the same number that it held after the 2011 election. Since the National Assembly increased the number of seats from 53 to 65, the PPP has held between 32 and 36 seats in total — a remarkably consistent result that demonstrates just how closely race, ethnicity and politics are intertwined in Guyana.

Just around 4,500 votes separated the PPP from the Granger-led coalition comprised of A Partnership for National Unity (APNU) and the Alliance for Change (AFC). Ramotar and the PPP have nearly a month to file a formal challenge to the result and seem highly inclined to do so. A recount that overturns Granger’s victory could bring widespread mistrust in a country that’s so sharply divided on racial and ethnic lines.

Granger has made the standard promises of a ‘change candidate’ — reducing corruption, boosting economic growth, reducing poverty and governing in a more inclusive style. Granger was sworn in over the weekend and, despite grumbling from the PPP, Guyana appears to have survived its first transfer of power following a truly competitive democratic election. Oil revenues, if used responsibly, could make his job a little easier, but no one should expect miracles.