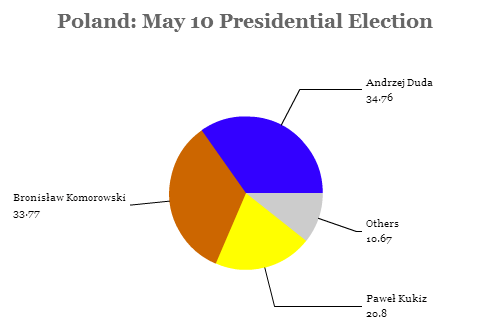

It’s safe to say that Polish president Bronisław Komorowski’s surprise second-place finish in the first round of the presidential election on Sunday was one of the most unexpected events in Polish politics of the past decade.![]()

Even after exit polls showed Komorowski (pictured above) training the conservative Andrzej Duda, it was still difficult to believe the popular, capable, moderate incumbent could have failed in a race where polls previously gave him a wide lead.

Though the presidency is chiefly ceremonial, the president serves as commander-in-chief of the Polish army and represents Poland in international affairs, though the prime minister (nominally selected by the president) establishes foreign policy. Notably, the Polish president also has a veto right over legislation, though a three-fifths majority of the Sejm, the lower house of the Polish parliament, can override a presidential veto.

The presidential vote is widely seen as a prelude to the more important parliamentary elections expected to take place in October 2015.

Complacency among Komorowski’s supporters, the gradual rise in support for Duda (pictured above) and the surprisingly robust protest vote for former rock musician Paweł Kukiz, who waged a populist campaign that called for more direct representation in national elections. Kukiz demands the elimination of party-list proportional representation and the introduction of single-member constituencies, with legislators individually responsible for their voters’ demands. Ironically, Kukiz’s call for a first-past-the-post system coincides with widespread dissatisfaction with the electoral process in Great Britain, where the FPTP system made for some rather inequitable results in last week’s election. Nevertheless, Kukiz won over one-fifth of all voters on Sunday, and both remaining candidates are keen on winning over his supporters.

Both candidates will now advance to a May 24 runoff and, though Komorowski is still expected to win reelection, there’s a chance that Duda could use the momentum of his first-round victory in the next two weeks to propel himself into the presidency. Duda, a 42-year-old member of the European Parliament, is the candidate of the nationalist, conservative Prawo i Sprawiedliwość (PiS, Law and Justice) that held power between 2005 and 2007. Unlike Komorowski, he opposes plans for Poland to join the eurozone.

* * * * *

RELATED: Kopacz puts imprint on Poland’s new government

* * * * *

Komorowski, nominally an independent but tied closely to the more pragmatic governing Platforma Obywatelska (PO, Civic Platform), receives generally high marks for his performance as president. Komorowski, a former defense minister, has struck a reassuring tone on the threat of growing Russian ambitions in Ukraine and eastern Europe, and his reelection campaign has sought to reassure voters that he will be a steady hand with respect to Poland’s security.

Kukiz refuses to endorse Komorowski in the second-round vote (but not, pointedly, Duda). The conventional theory is that Kukiz’s supporters are dissatisfied Komorowski voters who wanted to send a first-round message of discontent with the wider Polish political system. Of course, there’s every chance that Kukiz voters will back Duda, whose popularity has grown stronger than his party, or they’ll simply refuse to support either candidate on May 24.

Komorowski was quick to start wooing their support, however, pledging a referendum on electoral reform on Monday — before the official results were even announced. After refusing to join a first-round debate, Komorowski is now expected to join Duda in a one-on-one showdown later this month. Earlier today, he won the endorsement of Aleksander Kwaśniewski, who served as Poland’s president between 1995 and 2005.

Komorowski’s stumbles may portend difficultly for Civic Platform in the October parliamentary elections. The party first won power in 2007, and it steered Poland through the 2008-09 global financial crisis and the subsequent European sovereign debt crisis. Though Poland is not currently a member of the eurozone, it is nominally obligated to join at some point in the future under the terms of its accession to the European Union in 2004. Rare among European nations, Poland continued to grow throughout the dual financial crises. Even though it has slowed from a post-crisis peak of 4.8% in 2011, GDP growth picked up in 2014 to an anticipated pace of 3.3%, and economists expect a similar growth rate in 2015. The country has the largest economy in, and it is the emerging economic engine of, central and eastern Europe.

Nevertheless, for an emerging economy like Poland, those growth rates don’t necessarily feel like a boom to everyday voters. Polish GDP per capita is between $14,000 and $14,500 — far below the EU average of around $36,000 and less than in Latvia, Lithuania, Estonia, the Czech Republic and even post-crisis Portugal and Greece.

Moreover, after former prime minister Donald Tusk left national politics last year to assume the presidency of the European Council (the first time an eastern or central European has held one of the EU’s top positions), his successor, Ewa Kopacz, is vying for her first electoral mandate. Only the country’s second female head of government, Kopacz is a Tusk loyalist and the former marshal (essentially, speaker) of the Sejm. Unassuming and folksy, Kopacz’s party leads, if only narrowly, in opinion polls.

Law and Justice, still headed by former prime minister Jarosław Kaczyński, the twin brother of Poland’s late president Lech Kaczyński, lies to the right of Civic Platform. It’s a party that draws much more heavily on nationalist, social conservative and religious themes, and it’s strongest in Poland’s south and east. Kaczyński, whose brother died in an airplane crash over Russia in 2010, has spun wild conspiracy theories about the crash, which killed dozens of top Polish officials, reflecting widespread suspicion about Russia, which has only been exacerbated by Russian advances in Ukraine. If Duda fails to win the presidency on May 24, there’s a chance that he could force Kaczyński out of the leadership and possibly make the party more competitive in October. Though neither Tusk nor Kopacz has been too enthusiastic to move Poland toward eurozone accession, Duda and his party outright oppose eurozone membership.

Komorowski, a former dissident in Soviet-era Poland, rose to the presidency in an acting capacity in 2010 after Lech Kaczyński’s tragic death. He thereupon defeated Jarosław Kaczyński by a narrow 5% margin in the July 2010 runoff.

Though most of the attention fell on the top three contenders, the fourth-placed candidate, eurosceptic Janusz Korwin-Mikke, won 3.22%, and his newly formed Coalition for the Renewal of the Republic – Freedom and Hope, a split from another new right-wing party, hopes to make a splash in October as well on a stridently anti-European message.

Magdalena Ogórek, a 36-year-old historian who failed to win election to the Sejm in 2011, won just 2.42% of the vote, demonstrating the long-term and widening irrelevance of the political left in Poland. The Sojusz Lewicy Demokratycznej (SLD, Democratic Left Alliance) lost power in the 2005 parliamentary elections and has yet to recover. That’s made Poland an odd place where the chief ideological divide is not left versus right, but the business-friendly center-right versus the nationalist, social conservative right.