Despite headlines that are raising eyebrows both in Brazil and abroad, talk of Dilma Rousseff’s impeachment is still more smoke than fire.![]()

But the risk of impeachment proceedings will only increase as the corruption scandal surrounding Petróleo Brasileiro S.A. (‘Petrobras’), the state oil company, intensifies. Though impeachment talk may be premature today, it will not be so farfetched if Rousseff is personally linked to the Petrobras kickbacks or if it’s found that illegal funds financed Rousseff’s reelection campaign last year.

Nearly two million Brazilians have now signed a petition demanding her impeachment, and rising protests throughout a handful of Brazilian cities could spread more widely — perhaps even to levels seen during the 2013 protests.

As Brazil readies to host the first-ever South American Summer Olympics in 2016, Rousseff will brace for more criticism that the country can ill afford new stadiums at a time when many Brazilians, especially in Rio de Janeiro and its largest cities, still live in poverty. The real‘s value has dropped by more than 25% in the last year, inflation is rising, GDP growth is expected to stall in 2015 and Rousseff has committed to new austerity policies to allay fears in the bond markets about Brazil’s budget. More ominously, as her approval ratings plummet, and she faces emboldened domestic opposition, Brazilians have a ready precedent in the impeachment of Fernando Collor 23 years ago.

* * * * *

RELATED: Petrobras scandal highlights 12 years of Brazilian corruption

* * * * *

Rousseff, who narrowly won reelection last October, served as Brazil’s minister for mines and energy between 2003 and 2005, when the alleged corruption abuses are said to have begun. Even if Rousseff doesn’t face formal impeachment hearings, the whiff of scandal surrounding her adds to the sense that Rousseff and her party, the Partido dos Trabalhadores (PT, Workers Party), now in its fourth consecutive term in power, have become hopelessly corrupt. That could undermine Rousseff’s efforts to accomplish much in her second presidential term, including efforts to turn around Brazil’s stumbling economy. It could also complicate any efforts by beloved former president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (pictured above with Rousseff) to make a comeback bid in 2018.

Lula da Silva and the PT are no stranger to corruption scandal. In 2005, Lula da Silva’s government faced the ‘Mensalão’ scandal (a slang term meaning ‘big monthly payoff’), in which his government bought the support of over three dozen Brazilian lawmakers with $12,000 monthly stipends. Though Lula da Silva himself wasn’t charged or convicted of any misdeeds, the scandal resulted in several high-profile sentences.

With friends like these…

The first major blow to Rousseff’s second-term hopes came last month, when the lower house of Brazil’s national congress, the Câmara dos Deputados (Chamber of Deputies) elected as its president Eduardo Cunha, a member of the broad-tent Partido do Movimento Democrático Brasileiro (PMDB, the Brazilian Democratic Movement Party), an amorphous party that has found its way into government since the 1990s in both center-right and progressive governments alike. Ostensibly, Cunha and the PMDB are Rousseff’s allies. But Cunha is a social conservative who will block any progress on issues like abortion or LGBT rights, and he might even block Rousseff’s economic policies as well.

In his role as Chamber president, Cunha would have to approve any impeachment petition before full hearings could begin. For now, Cunha has rejected as premature and irresponsible any talk of impeachment. But that could change if Rousseff becomes even more unpopular, especially as a result of further implication in the Petrobras scandal.

As a matter of process, two-thirds of the Chamber (342 legislators) would have to approve the impeachment request before sending it to the Senado (Senate) for consideration. At that point, Rousseff would be forced to step down for up to 180 days during the Senate’s deliberation. Another two-thirds majority (54 members) would be required to convict Rousseff.

Photo credit to Anderson Reidel.

Photo credit to Anderson Reidel.

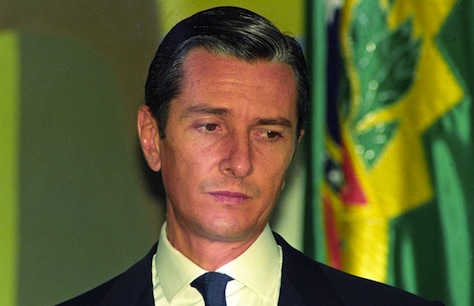

Rousseff’s vice president, Michel Temer (pictured above), is also a member of the PMDB, and he would assume the presidency in the event of a Rousseff impeachment conviction or resignation. The 74-year-old Temer, of Lebanese descent, first won election to the Chamber of Deputies in 1987, where he represented São Paulo for nearly a quarter-century until joining Rousseff’s ticket as her running mate in the 2010 election. Throughout the 2000s, he led the PMDB, and he twice served as the president of the Chamber of Deputies, the first time between 1997 and 2001.

While Temer hasn’t disavowed the opportunity to end his career in Planalto, the Brazilian presidential palace, he would almost certainly inherit a poisoned chalice — a stagnating economy and heightened scrutiny in the PMDB’s own role in governmental corruption, which would almost certainly handicap his chances to win reelection in his own right in 2018.

In the meanwhile, the corruption scandal at Petrobras — and Rousseff’s response to it — has only worsened. As investigators have discovered up to $8 billion in potential kickbacks, the Brazilian government fired the top Petrobras management in February, including its president Maria das Graças Foster, a longtime Rousseff chum. The confusion surrounding the process has complicated both domestic and international commercial relations with Petrobras and third parties, creating even more drag on the troubled economy and accelerating the cascade of global investors out of Petrobras.

Moreover, few Brazilians took much faith in Rousseff’s choice for Petrobras’s new chief executive — Aldemir Bendine, formerly Brazil’s central bank president and a figure seen as close to the governing PT. Petrobras shares dropped by nearly 10% last month when Rousseff announced Bendine’s appointment.

The ghost of Collor

If Rousseff is eventually drawn closer into the Petrobras debacle, and she herself is found to have directed or even taken kickbacks, she will clearly be well within Collor territory.

Though he came from a longstanding political family, a youthful Collor (pictured above) won the 1990 election with neoliberal plans to unlock Brazil’s sluggish economy. But he resigned the Brazilian presidency in disgrace after barely more than 30 months in office. Despite his resignation, Collor was ultimately impeached and found guilty of corruption charges by the Brazilian legislature, disqualified from office for eight years and left to fend off criminal charges for his misdeeds, which involved an influence-peddling scheme with his campaign treasurer first exposed (of all people) by Collor’s own brother.

After his ban on political participation ended, Collor tried to win office several times before winning election to the Brazilian Senate from Rio de Janeiro as a member of the center-right, opposition Partido Trabalhista Brasileiro (PTB, Brazilian Labour Party). Ironically, that means Collor would hold one of the 81 votes in any impeachment trial.

The 1992 impeachment proceedings were something of a test for Brazilian democracy, less than a decade removed from military rule, but the fact that Brazil’s legislature vigorously held Collor to account showcased the country’s commitment to the rule of law and its competitive political marketplace.

It’s still too soon to write off Rousseff and the Workers Party, which strong-armed the popular Marina Silva out of the first round of last October’s presidential election before dispatching former Minas Gerais governor Aécio Neves in the runoff. But Rousseff’s 2015 will not be pleasant.