While the rest of Europe focused on the Paris march following last week’s terrorism attacks, Croatia attended to the business of electing a new president.![]()

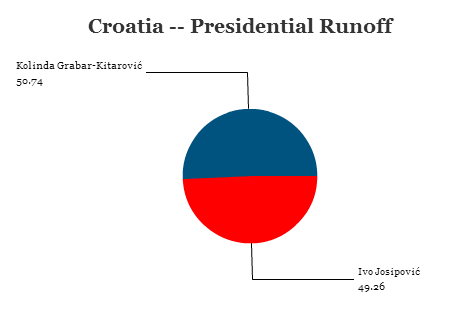

Kolinda Grabar-Kitarović, who is associated with the center-right opposition, the Hrvatska demokratska zajednica (HDZ, Croatia Democratic Union), defeated incumbent president Ivo Josipović, nominally an independent but associated with the governing, social democratic Kukuriku coalition, an electoral group of four center-left parties.

That Josipović won the first-round vote on December 28 and only closely lost Sunday’s vote to Grabar-Kitarović is a testament to his popularity, not to the weakness of the HDZ. But for a party that believes it’s on the verge of returning to power — Croatia must hold parliamentary elections no later than February 2016 — it might have expected to do better. Grabar-Kitarović narrowly won by a margin of around 20,000 votes, many of which came from Croats living abroad in neighboring Bosnia and Herzegovina. In the first round, she won over 77% support among Croats abroad, and she made promises to support the Bosnian Croat population.

The HDZ easily defeated the Kukuriku coalition in last May’s European parliamentary elections, and polls give the HDZ a lead of between 6% and 9% in advance of the next national elections. One new party, the Održivi razvoj Hrvatske (ORaH, Sustainable Development of Croatia), is attracting increasing support, however — it was formed only in October 2013 as a green, leftist alternative to the current government by former environmental minister Mirela Holy. Social Democratic prime minister Zoran Milanović, who took office in 2011, has faced the wrath of an electorate weary, like the rest of southern and central Europe, of poor economic conditions, despite the fact that he presided over Croatia’s accession as the 28th member-state of the European Union in July 2013.

Nevertheless, the HDZ will be happy enough to have installed Grabar-Kitarović as Croatia’s first female president, a role that is essentially ceremonial though, like in most European parliamentary democracies, Grabar-Kitarović plays a role in foreign affairs and defense policy and she is technically in charge of appointing the prime minister following elections. In the context of the Balkans, however, the president can play an important diplomatic role for a region just two decades removed from war. Josipović, for example, made a controversial speech in Sarajevo during his presidency when he expressed deep regret for Croatia’s involvement in the Bosnian civil war. (Note that Atifete Jahjaga, elected in 2011 to the presidency by Kosovo’s parliament, is the first female head of state in former Yugoslavia, as a region).

No one should expect Grabar-Kitarović to make any apologies during her term. She is, somewhat controversially, a fan of Croatia’s first post-independence leader, Franjo Tudjman, an often autocratic and nationalist president throughout the turbulent 1990s and founder of the HDZ. During the campaign, Grabar-Kitarović promised to ‘return’ to where Tudjman stopped, raising some eyebrows.

Grabar-Kitarović served as European affairs minister between 2003 and 2008 and became, in addition, its foreign minister from 2005 to 2008, laying much of the groundwork for the country’s accession to the European Union, only the second Balkan country to achieve member-state status (after Slovenia). From 2011 to 2014, she served as NATO’s assistant secretary general for public diplomacy.