Even before the gruesome murder of 12 civilians today in the name of Islam, France wasn’t exactly having the best run. ![]()

Nicolas Sarkozy came to power in 2007 amid promises of rupture and reform, signaling youthful, nervous energy that would transform France’s public sector after the somnolent 12-year reign of the genteely corrupt Jacques Chirac. While he did manage to raise the retirement age and make some tweaks, the full-throated rupture never quite arrived, and his administration amounted to an embarrassing series of bling bling moments, capped off by his whirlwhind romance and marriage to singer Carla Bruni. It’s still hard not to cringe at the photos of Sarkozy and Bruni at Disneyland Paris just months after his inauguration or the thought of Sarkozy lapping up the excesses of wealth on one of Silvio Berlusconi’s yachts.

François Hollande easily defeated his reelection bid in May 2012 with a promise to boost growth and employment in policy matters and to be a ‘normal’ president in, ahem, more personal matters. France got neither from its new president, whose popularity rating today is stuck in the high 10s or low 20s, depending on the poll. Even before the 2012 election campaign ended, his then-consort Valérie Trierweiler had already gotten into a spat on Twitter attacking Hollande’s former partner of three decades, Ségolène Royal, herself a former presidential candidate and a top figure within the Socialist Party. That presaged the ridiculous split between the two earlier this year, catalyzed by the impotent image of Hollande sneaking out of the Elysée Palace on a scooter for a tryst with French actress Julie Gayet. Charlie Hebdo, it should be noted, ruthlessly mocked Hollande for his shortcomings as well as organized religion of all faiths:

If the United Kingdom held the ‘sick man of Europe’ crown in the 1970s and Germany held it in the 1990s before its labor market reforms and amid the tectonic growing pains of reunification, France would hold clear title to that position today, if not for so many other pretenders across Europe, each struggling under the strains of joblessness, economic malaise, depopulation and precarious public debt. After starting to fall in 2013, France’s unemployment rate leapt back to record levels (10.4%) at the end of 2014. Short of a contentious battle to legalize same-sex marriage and his soon-forgotten success from decisive military action to liberate northern Mali from jihadists, Hollande has precious few policy victories to show for his administration.

It might be more accurate to call France the ‘invisible man’ of Europe.

While Germany has emerged, for now, as the sole engine of Europe, its chancellor Angela Merkel dictating fiscal policy to the rest of the European Union and its central bankers vetoing the kind of aggressive eurozone-wide quantitative easing that could reverse deflationary trends, you don’t hear much talk about the vaunted Franco-German axis anymore. British prime minister David Cameron, who’s courting disaster in his promise to hold a referendum on his country’s EU membership, has more influence on the German chancellor than Hollande or even his relatively right-leaning prime minister Manuel Valls, who leads Hollande’s second government in three years. Whether it’s banking unions or Russian aggression in eastern Europe or eurobonds or the risk of a far-left Greek government in elections later this month, no one gives a hoot about what Hollande has to say on EU matters — or anything else for that matter.

As Sarkozy, plagued by legal challenges, plots a center-right comeback and Hollande’s center-left Parti socialiste (PS, Socialist Party) loses more credibility by the day, the xenophobic, far-right Marine Le Pen and the Front national (FN, National Front) are basking in the victory of emerging as the top-placed party in last May’s European elections. Polls for the first round of the 2017 presidential election routinely place Le Pen leading or tied with all the major contenders, including Sarkozy and former foreign minister Alain Juppé, on the right, and Hollande and Valls, on the left. But you could see the rumblings a decade ago, when the French single-handedly ended the push (led by former French president Valéry Giscard d’Estaing, no less!) to draft a constitution for the European Union, when voters rejected the constitutional treaty in a May 2005 referendum.

We’ve all read too many stories in the past decade or so about the tristesse or the ennui afflicting modern 21st century France.

So it’s understandable that so many commentators looked at the horrific attack on the Charlie Hebdo office on Tuesday and worried that it would unleash a wave of anti-Muslim sentiment, fueling the insular nationalism that drives Le Pen and the French far right, which has responded to France’s collective economic slump by lashing out at the political elite, at immigration and at the European Union.

But as Juan Cole wrote in one of the most astute reactions to the Charlie Hebdo massacre, that’s exactly one of the motivations for the crude tactics of radical Islam, which attracted much interest among France’s five million Muslims, who comprise around 8% of France’s 66 million-strong population:

Al-Qaeda wants to mentally colonize French Muslims, but faces a wall of disinterest. But if it can get non-Muslim French to be beastly to ethnic Muslims on the grounds that they are Muslims, it can start creating a common political identity around grievance against discrimination…. This horrific murder was not a pious protest against the defamation of a religious icon. It was an attempt to provoke European society into pogroms against French Muslims, at which point al-Qaeda recruitment would suddenly exhibit some successes instead of faltering in the face of lively Beur youth culture (French Arabs playfully call themselves by this anagram). Ironically, there are reports that one of the two policemen they killed was a Muslim.

Instead of instinctively falling into some cartoon mould of right-wing xenophobia, most of what we saw from Paris, from France and much of the rest of the world were precisely those things about which France should be proudest — the freedoms and rights that necessarily follow from the liberté, égalité and fraternité that have formed the heart of French public life since the 1789 revolution.

Far from embracing knee-jerk anti-Muslim sentiment, the world watched as France, implausibly, united behind Hollande, who actually looked like a president for perhaps the first time since his election. They rallied in city after city, from Paris to Marseille and beyond, not to excoriate a religion or five million French Muslims, but to defend freedom of expression and speech. No one’s burning down banlieues tonight in France.

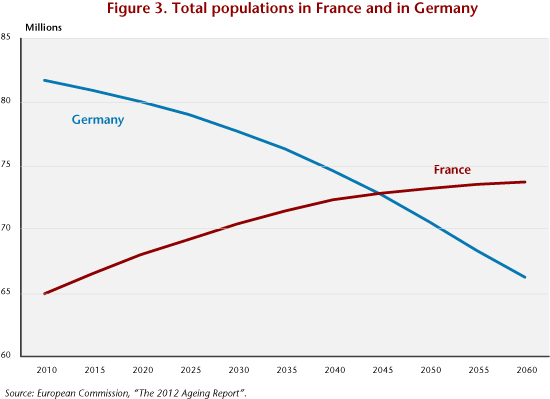

In taking to social media with the simple Twitter tag #JeSuisCharlie, millions of French reminded each other of all the things that made France great — and will make it great once again in the 21st century. After all, if France is going through its ‘sick man’ phase now, it won’t be there forever — compared to Germany, France’s birthrates are edging higher, so much so that by mid-century, Germany’s declining population could sink far below France’s. It might once again be a French president calling the shots on EU-wide policy, with Germany’s chancellor shunted to the sidelines.

There are no silver linings to a tragedy like Tuesday’s.

But events like these have a way of bringing together a country and its people in surprising and unpredictable ways. For the United States, in 2001, it meant launching the country on the path to a controversial war on terror, through the mountain passes of Kabul and Pakistan to the deserts of Iraq, and the effects of all of it are still unfolding and unknowable today. For Norway, in 2007, when right-wing maniac Anders Behring Breivik killed 77 people in a single day, the country responded by defiantly defending its open culture of freedom and transparency.

France may now be having a similar moment. In another decade’s time, we may point not to the Charlie Hebdo killings, but to the overwhelming response to its aftermath as a key pivot in France’s existential resurgence, the moment when France collectively regained its footing. After years of mourning what France lost or what France has failed to achieve or accomplish, tonight was a rare chance to celebrate France’s collective values in the face of intolerance and horror.

3 thoughts on “In Charlie Hebdo massacre, French values find a rallying point”