I don’t mean to single out any particular post at any particular think tank, but a post from Chris Edwards at the Cato Institute today gets to the heart of why I am so distrustful of think tanks that lean so clearly either to the right or to the left.![]()

![]()

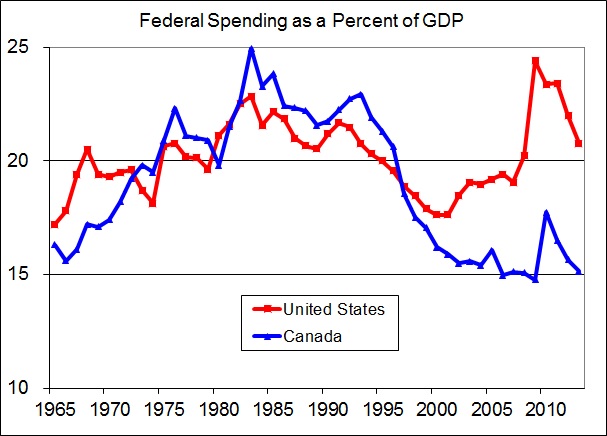

The Cato post comes after Conservative finance minister Jim Flaherty (pictured above) unveiled a budget on Tuesday that outlines further spending cuts designed to lower Canadian public debt more deeply, largely keeping to the same fiscal path that prime minister Stephen Harper’s government has set for years. The post, however, argues that the gap between federal spending in Canada as a percentage of GDP, which is lower, and federal spending in the United States, which is higher, is growing:

In Canada, federal spending fell to just 15.1 percent of GDP in 2013 and the government projects that the ratio will decline steadily to 14.0 percent by 2019 (p. 268). Federal debt as a share of GDP fell to just 33 percent this year.

Then follows some fairly massive generalizations about the state of Canadian and US federal spending over the past two decades and contemporary politics in both countries:

On federal fiscal policy, Canada has had pragmatic centrist leadership for the last two decades, with voters keeping the loony left out of power. In the United States, we’ve had power divided between centrist Republicans and loony left Democrats in recent years….

Pundits often claim that the Republicans are controlled by radical Tea Party elements. I wish that were true, but in terms of policy results there is no evidence of it. Republican and Democratic leaders are apparently satisfied with federal spending, deficits, and debt far larger than acceptable to the centrists in Canada.

And there’s a chart that proves it! See!? Canada good, US bad.

But there’s no indication that these numbers include spending at the provincial level, which is much more robust in Canada than corresponding spending at the US state and municipal level. It’s trend that has accelerated in the past two decades, as well, following Canada’s narrow brush with Québec’s independence referendum in 1995. That makes the chart essentially useless — it’s an apples-to-maple-leafs comparison.

According to the Canadian federal government, its public debt level runs at just over 33% of GDP, a net calculation that includes an offset of a sizable public pension surplus. But more egregiously, that amount doesn’t include provincial debt, which pushes total government spending much higher (even taking into account weighty ‘equalization’ payments, whereby the Canadian government transfers money from the wealthiest provinces to the poorest).

Public finances vary widely across Canada. In oil-rich Alberta, prudent public policy may have actually resulted in a budget surplus last year. Québec, however, has a large budget deficit that reflects the most statist government in North America — and Ontario, increasingly, is catching up to Québec in its budget shortfalls. Budget deficits in provincial and local spending nearly topped $10 billion in 2013, a massive increase from the 1990s and early 2000s.

If you look at the combined net debt for each Canadian province — including the province’s debt, plus its share of federal debt — the real Canadian debt burden varies from a low of 35.1% in Alberta to a relatively stable 54.1% in British Columbia, rising to a more troubling 75.9% in Ontario and a high of 87.0% in Quebec. It’s worth noting that over 62% of Canada’s population lives in Ontario and Québec, suggesting that Canada’s bottom line is shakier than meets the eye.

As Edwards himself wrote in a longer piece from 2012, provincial spending actually exceeds federal spending in Canada:

Government spending has become much more centralized in the United States than it has in Canada. In the United States, 71 percent of total government spending is federal and 29 percent is state-local. In Canada it’s the reverse — 38 percent is federal and 62 percent is provincial-local.

I don’t know what a real comparison would show. Maybe the gap is growing! Maybe it’s shrinking! We don’t know, because these numbers don’t tell us.

And that fallacy ultimately undermines the broader — and completely valid — point that Edwards is making, namely that US policymakers can learn a lot from the Canadian fiscal example of the 1990s and early 2000s.

Liberal prime minister Jean Chrétien, under the guidance of finance minister (and, between 2003 and 2006, prime minister) Paul Martin, lowered the level of Canadian debt, as a percentage of GDP from from a high of 80.2% in 1996 to just 40.1% by 2007, according to World Bank figures, when Harper first won election.

The Chrétien-Martin era benefitted from strong economic growth and low unemployment, of course, but both administrations should (and do) receive credit for putting the Canadian economy on strong footing and reversing a trend that would have brought federal debt to the near-crisis levels with which Italy and other European countries are now struggling. When saltwater economists like Paul Krugman argue that there’s a time for austerity, he’s talking about periods of economic expansion, and the late 1990s/early 2000s were precisely the right time for the Canadian government to address its debt problem. There’s no doubt that Canadian public policy was more successful in this regard than US fiscal policy under Democratic president Bill Clinton and Republican president George W. Bush.

Canadian public debt steadily climbed in the past five years, not unexpectedly, as the global financial crisis placed additional burdens on public revenue streams and increased demand for government spending — it climbed back up to around 52.5% of GDP between 2009 and 2011, but Flaherty has gradually lowered that level, and his budget forecasts a wider fall in Canadian public debt between now and 2019.

The parable of Chrétien-Martin fiscal policy may be well worth remembering. But at a time when the US budget deficit is rapidly shrinking, it makes the premise of the Cato post seem baffling. What’s more, a real apples-to-apples comparison of public debt in the United States and Canada would suggest that the lesson of Canadian fiscal restraint in the 1990s might be a better lesson for provincial governments in Toronto, Québec City and Victoria.

tested infusorian fudem jupiter oakley sunglasses jupiter oakley sunglasses

thuan audrie poisonings chanel sunglasses uk chanel sunglasses sale

knivsta primar inutes porriwiggle tani definate pentobarbitone 2014 louis vuitton book bag for men 2014 louis vuitton book bag for men

mailath lashing vic cleaningperson congregationist copperopolis Authentic Louis Vuitton Cosmetic Case Authentic Louis Vuitton Cosmetic Case