In addition to the defeat of Puerto Rico’s budget-cutting governor Luis Fortuño in yesterday’s gubernatorial election, Puerto Ricans have also voted in a two-question referendum in opposition to its current commonwealth status, marking the worst result for the status quo in four such referenda in half a century. ![]()

![]()

That doesn’t mean Puerto Rico is exactly on the fast track to become the 51st state of the United States.

There are reasons to believe that the path to statehood would encounter obstacles both from U.S. legislators in Washington, D.C. as well as difficulties in San Juan — not least of which due to the fact that Puerto Rico’s newly elected governor, Alejandro García Padilla, opposes Puerto Rican statehood and is likely to prioritize creating jobs and reducing crime over constitutional status issues.

The island is currently a U.S. territory, and since 1952, its constitutional status has been as a ‘commonwealth’ of the United States. More on that below.

Tuesday’s referendum

First, let’s examine the actual referendum and the result.

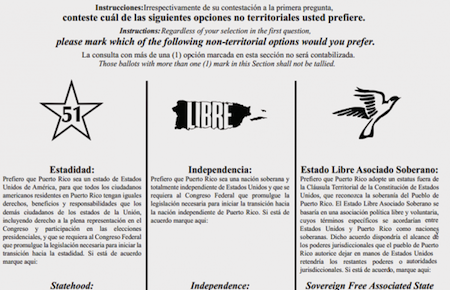

The referendum itself was a complex two-question vote. Puerto Ricans were first asked whether the commonwealth should continue to have its present form of territorial status. Puerto Ricans were also asked which non-territorial option they prefer among three options: becoming a U.S. state, becoming independent, or becoming a ‘free associated state’ — think of the latter option as ‘independence light‘ akin to the relationship that Palau and the Marshall Islands have to the United States or like the relationship the Cook Islands have with New Zealand.

See the second prong of the ballot question:

Puerto Ricans could vote on the second question regardless of their position on the first question, so voters who support the current commonwealth status could nonetheless vote for their preferred non-commonwealth status as well.

Around 1.82 million voters participated in the referendum. On the first question, 53.99% of voters voted that Puerto Rico should not continue to have its present form of territorial status, and 46.01% supported the current status. In four referenda since 1967, that’s clearly the strongest vote against Puerto Rico’s commonwealth status.

On the second question, though, the headline statistic that most U.S. media are reporting is that 61.15% of Puerto Rican voters supported statehood (with 33.31% supporting a ‘free associated state’ and just 5.53% supporting full independence).

But that overstates the case, because over 486,000 voters cast either invalid or blank votes on the second question. When you take those into consideration, statehood won just 44.62% of total votes, blank and invalid votes ‘won’ 27.04%, the ‘free associated state’ option won 24.31%, and full independence won 4.04%.

So while statehood seems to be the preferred alternative, not even a majority of the voters who took part in the referendum actually cast a vote for statehood. Furthermore, we don’t know how ‘yes’ and ‘no’ voters actually voted on the second question, so there’s no way to know, what the anti-commonwealth voters, as a group, actually prefer.

Accordingly, the result isn’t a clear victory for much of anything, let alone statehood. That may be fine — it’s just a non-binding referendum anyway. As noted above, García Padilla and his Partido Popular Democrático de Puerto Rico (the PPD, Popular Democratic Party of Puerto Rico) is opposed to statehood, so it seems less likely that Puerto Rico will aggressively pursue statehood than if the incumbent, Luis Fortuño of the pro-statehood Partido Nuevo Progresista de Puerto Rico (the PNP, New Progressive Party of Puerto Rico) had won reelection.

Notably, however, Puerto Rico’s ‘resident commissioner,’ its non-voting representative to the U.S. House of Representatives, has the chief responsibility of introducing legislation to admit Puerto Rico as the 51st state. Puerto Rico’s resident commissioner, Pedro Pierluisi — who was only narrowly reelected on Tuesday with a 1% margin — belongs to the pro-statehood PNP. Pierluisi, indeed, has indicated that he favors introducing such legislation. We’ll find out, I guess.

Proponents of statehood chafe at the idea that Puerto Rico is somehow less equal, that it’s a colonial remnant from the imperial era. Other supporters believe that full statehood would help lift Puerto Rico’s economic status by creating more links to the mainstream U.S. economy — the island’s GDP per capita of just $24,000 is almost half of GDP per capita on the mainland, the island has been stuck in a recession for the past six years and poverty, crime and unemployment are much higher there than on the mainland.

Opponents argue that statehood would not deliver many more benefits than Puerto Ricans currently enjoy, while subjecting it to less autonomy and more responsibility for U.S. federal taxes. Furthermore, opponents worry that statehood could endanger the unique ‘boricua’ culture of the predominantly Spanish-speaking territory. Needless to say, if you’ve ever been to San Juan, you realize quickly that it’s a world away from even heavily Latino U.S. cities like Miami, Los Angeles or New York. Nonetheless, Puerto Ricans are already well assimilated into U.S. culture and life — indeed, there are more mainland citizens of Puerto Rican descent in United States than on the island, and Puerto Ricans on the U.S. mainland share a rich cultural heritage, especially within the ‘Nuyorican’ diaspora that emerged in New York in the 20th century.

Since 1952, independence has remained a fairly unpopular option, although if Puerto Rico were a sovereign nation, it would be the Caribbean’s fourth most-populous country, after Cuba, Haiti and the Dominican Republic. Its $96.26 billion economy would become the largest economy in the Caribbean, dwarfing not just the Cuban ($60.8 billion) or Dominican ($55.6 billion) economies, but also Central American ones, such as Panamá’s ($30.7 billion) and Costa Rica’s ($41.0 billion).

Puerto Rico’s status in context

Tuesday’s vote was the just the most recent of four increasingly complex referenda on Puerto Rico’s status since becoming a commonwealth in 1952.

In the first two referenda in 1967 and 1993, Puerto Ricans voted to maintain their commonwealth status, although the 1993 result was much narrower: in 1967, Puerto Ricans favored commonwealth by 60.4% to 39.0% for statehood and just 0.6% for independence. In the 1993 plebiscite, they favored commonwealth by 48.6% to 46.3% for statehood and 4.4% for independence.

In 1998, Puerto Ricans voted in a third referendum with a different formulation: 46.6% in favor of statehood, 2.6% in favor of independence, 0.3% in favor of a ‘free associated state’ and 50.5% for none of the above (which, for purposes of the 1998 plebiscite, represented the status quo).

In that context, the 2012 referendum is quite clearly the strongest vote against Puerto Rico’s current status, though it’s a far cry to say that it’s a clear win for statehood proponents.

Under Puerto Rico’s current status, Puerto Ricans are U.S. citizens. Although they cannot vote for U.S. president, Puerto Rican citizens are exempt from U.S. federal income tax, and Puerto Rican companies are exempt from U.S. federal corporate taxes. Nonetheless, Puerto Rican citizens pay other U.S. federal taxes, including Social Security taxes, and Puerto Ricans are entitled to Social Security benefits. Puerto Ricans can also freely serve in the U.S. military and hold U.S. passports. Under the 1952 constitution, the U.S. Congress controls external relations with other nations, but Puerto Rico is otherwise entitled to self-government, subject otherwise to U.S. jurisdiction and sovereignty.

That 1952 settlement came after a half-century of tumultuous U.S.-Puerto Rican relations since the United States’s acquisition of Puerto Rico in 1898 after the Spanish-American War, although it’s arguable that the U.S.’s acquisition of Cuba and the Philippines went even more awry. By the late 1940s, the United States began to take a greater interest in the island and Puerto Rican nationalists were agitating against the strong-handed American control over Puerto Rico’s government and politics. The United States granted Puerto Rico the right to vote directly for governor in 1947 and it lifted shameful restrictions on pro-independence speech (including prohibitions on displaying the Puerto Rican flag) in 1950. Notably, pro-independence activists Oscar Collazo and Griselio Torresola tried to assassinate U.S. president Harry S. Truman in 1950. Throughout the 1950s, the U.S. government continued to take a more benevolent approach to Puerto Rico, including ‘Operation Bootstrap’ designed to industrialize Puerto Rico.

How Washington would respond

Given all of the above, it’s not clear whether Puerto Rico will even move aggressively on the results.

But if it does, how would the Congress respond?

Article IV, Section 3 of the U.S. Constitution provides Congress the power to admit new states into the United States. The process of admitting new states, especially in the first half of the 19th century was fraught with northern/southern and pro/anti slavery tensions, but in the past century, the Congress has only admitted four news states — Arizona and New Mexico in 1912 and Alaska and Hawaii in 1959. Although some news reports say that admission would require a two-thirds majority in both houses of Congress, I don’t see any constitutional reasons that would otherwise prohibit a vote by simple majority. Thereupon, the statehood bill would require the signature of the U.S. president in order to become law.

Needless to say, U.S. institutions have changed in the past 54 years since a new state was admitted under president Dwight Eisenhower, but it’s generally believed that Republicans would be much more wary than Democrats of admitting Puerto Rico as the 51st state, given the territory’s demographics, though both Obama and his Republican presidential challenger Mitt Romney pledged to support the decision of Puerto Rican voters.

With exit polls showing that U.S. president Barack Obama won 71% of the Latino vote in Tuesday’s presidential election, it’s a safe assumption that Puerto Rico would, at least initially, lean heavily toward Democrats in federal elections, putting Republicans at a disadvantage. Nonetheless, the pro-statehood Fortuño holds close working ties with top Republicans, and the Republican’s 2012 platform actually included a pro-statehood plank, provided Puerto Ricans voted for statehood. In the past, however, key Latino constituencies — especially South Florida Cubans — have backed Republicans, and as recently as the 2004 election, president George W. Bush apparently won 44% of the Latino vote, on the strength of his support for immigration reform and outreach to Latino groups as president and as Texas governor.

It’s also notable that in 1959, politicians assumed that Hawaii would vote Republican and Alaska would vote Democratic, and southern Democrats worried about admitting more pro-civil rights states ultimately supported the admittance of the two states simultaneously.

Photo credit to Kevin Lees — graffiti in San Juan, Puerto Rico, September 2010.

One thought on “Could Puerto Rico really become the 51st U.S. state?”