After one of the most raucous campaigns in Hong Kong’s — or China’s — history, Leung Chun-ying has emerged as the victor in Hong Kong’s election for a new chief executive.![]()

![]()

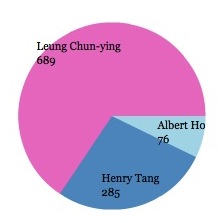

Leung won 689 votes from the 1,200-member Elections Committee to just 285 votes for Henry Tang and 76 for pro-democracy candidate Albert Ho:

The race had become unexpectedly chaotic over the past months — the initial frontrunner Tang was plagued first by infidelity accusations and then by more serious scandals about illegal construction of a basement in his home — culminating in a media frenzy outside his Hong Kong building. Tang was also almost certainly hurt by other corruption charges that recently emerged the outgoing chief executive Donald Tsang, in whose administration Tang had played key roles.

Although both Tang and Leung were seen as sufficiently pro-Beijing, Tang’s missteps and scandals made him wildly unpopular among the Hong Kong populace at large, with Leung leading most preference polls during the campaign.

Looking forward, perhaps the most important lesson of the race is that Hong Kong –and China — can withstand the sometimes messy process of popular democracy and the media coverage that accompanies it.

China has indicated it will permit a direct election in the 2017 chief executive race — if it follows through with that promise, PRC officials can look to the 2012 race as a promising precedent on the road to full democracy for the special administrative region. Beijing’s dexterity in shifting its support, however subtle, from Tang to Leung, demonstrates that it would have been able to recognize with equal grace a popular vote resulting in Leung’s election as well. More strident voices — like those of the Democracy Party and Albert Ho — have been met with damp enthusiasm from Hong Kong residents and elites alike, who are pragmatic in realizing that the chief executive must be able to work with, and not against, China’s leadership.

Although many of Hong Kong’s real estate tycoons made clear that they would stick with Tang — including Li Ka-shing, Asia’s wealthiest man, many leaders of the People’s Republic of China signaled over the past month that Leung was not only an acceptable candidate, but even Beijing’s preferred candidate. Earlier this week, other influential groups made clear they were moving toward Leung.

Tang, who had served as finance secretary or chief of administration in the Hong Kong leadership since 2003, had been groomed for the chief executive post, but Leung, who had served from 1999 to 2011 as the Convenor of the Executive Council of Hong Kong — a policy-making body that reports to the chief executive — was also a well-known quantity to Hong Kong government.

Leung, portrayed in the local media as a fox in regard to his reputation for cunning, successfully made the case that he would better address Hong Kong’s economic problems with more agility at a time when Hong Kong residents face ever-higher costs for housing. Tensions continue to rise in regard to Hong Kong’s role in China — residents have complained about the costs of relatively poorer migrants from the mainland, even as the wealthiest mainlanders have begun to challenge Hong Kong’s long-time identity as the top economic performer in east Asia. Leung connected more effectively with voters than Tang, a long-time insider and a textile businessman portrayed in the media, rather unflatteringly, as somewhat of an obtuse and dim-witted pig in contrast to Leung’s fox.

But Hong Kong worries have not been limited to economic insecurities — residents have long been wary of the PRC’s interference in the political and social freedoms that Hong Kong residents have cherished since the handover of the one-time British colony back to China in 1997. Although Leung’s election marks the election of the most genuinely popular candidate, he has been plagued with rumors that he is a secret member of China’s Communist Party and rumors that he has ties to the organized crime “triad” syndicates in Hong Kong. Tang, in the final days of the campaign, accused Leung of wanting to use riot police and tear gas against those protestors, striking a chord with Hong Kong residents who are keen to protect their political freedoms.

In his first remarks to the press following his victory, Leung promised to consult widely with the public on national security and other legislation, indicating that he will press forward with an anti-subversion law — Article 23 — that has been in the works for over a decade and which inspired mass protests in Hong Kong in 2003.

2 thoughts on “Leung wins in Hong Kong”