Faced with a deep economic slowdown for the first time since the 1970s, the headline news emerging today from the Chinese Communist Party (中国共产党) at its fifth plenum this week is that it will formally end its one-child policy as the country deals with the more pressing problem of a rapidly aging population.![]()

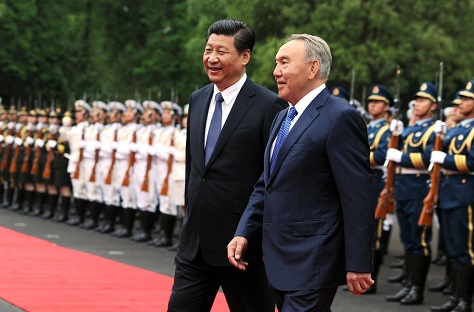

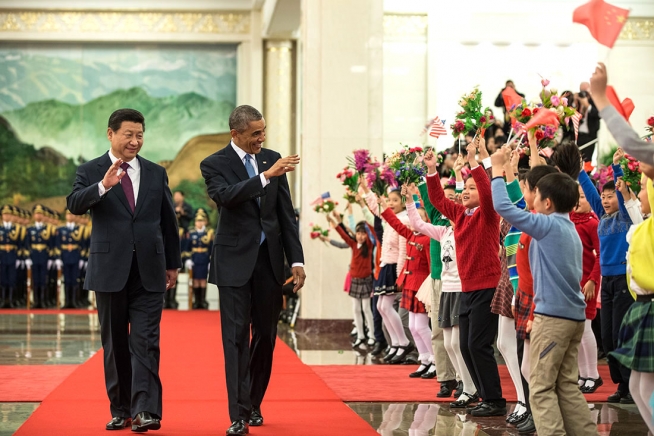

The meeting, where the Communist Party will design its 13th five-year program for the Chinese economy, is an important moment for ruling officials to chart the path that Chinese president Xi Jinping (习近平) will carry forward through the end of his first term and a second term to which Xi will presumably be selected in 2017.

Though the Chinese government has been relaxing the terms of the one-child policy for years, today’s step formally ends a policy first enacted in 1978 at a time when China’s economy and demographics were far different than today. In the wake of the post-Mao era, Chinese Communist officials worried that exponential population growth would worsen environmental problems that were becoming apparent four decades ago, spread too thinly resources for educating a new generation of Chinese children and keep the country mired in poverty.

* * * * *

RELATED: China’s stock market crash is a political, not economic, crisis

* * * * *

After introducing the one-child policy, China turned to the neighborhood associations that Mao Zedong created throughout the country to enforce the new family planning edict. Almost overnight, local party infrastructure became an essentially intrusive mechanism to keep Chinese families in line and restrict reproductive freedom in the name of collective development. Parents who violated the policy faced monetary fines and, in some cases, forced abortions or even forced abductions of their second child. Throughout China, second children essentially became pariahs, and they faced restrictions on government-funded health care and education.

Farmers in parts of rural China were exempted from the policy, especially when their first child was a daughter. Moreover, ethnic minorities (even in urban areas) were exempt from the policy as well. In 2013, China relaxed the policy even further by allowing parents to have two children so long as both parents themselves were only children. That exemption largely ended the policy, meaning that today’s decision to end the one-child policy is more a formality than a real change. In an era where Xi has cracked down on political dissent and Internet freedom and arguably launched a widespread crackdown on corruption to purge rivals within the ruling Party apparatus, today’s decision is a rare extension of Chinese freedoms.

Gauged by the worries of policymakers in the 1970s, the one-child policy has been a slight success. That’s at least insofar as parents and grandparents dote on a country full of only children, deploying each family’s resources on the educational and developmental progress of a single child. But it’s the country’s breakneck growth, not family planning, that played a far greater role in lifting China out of poverty. Four decades of economic liberalization and international trade, which began under Deng Xiaoping in the early 1980s, is responsible for that. It helped that China didn’t face the kind of turmoil that roiled it during World War II and the civil wars of the 1940s, the rural famine that marked Mao’s ‘Great Leap Forward’ of the 1950s or the political terror of the Cultural Revolution of the 1960s and 1970s.

Moreover, what’s become increasingly clear in retrospect is that the one-child policy may have accomplished far more harm than good by accelerating the aging of China’s population and by facilitating a highly imbalanced sex ratio of boys to girls.

The intellectual roots of the one-child policy lie partially in the problematic economic ideas of Thomas Malthus, who argued at the end of the 18th century that rapid population growth would be invariably met with disease, starvation and war. If left unchecked, a doubling of the population would burden the ability of a country’s land to generate enough food to support a demographic explosion. But the human experience over the ensuing two centuries has been exactly the opposite as innovations in agriculture have produced far more food with increasingly less labor. In the year 1800, global population is estimated to have been around one billion; today, it’s 7.4 billion and growing at a time when global poverty is in decline.

Moreover, by the time that China’s policymakers got around to introducing the one-child policy, China’s fertility rate was already rapidly declining, matching global trends in both the developing and the developed world, partially as a result of the widespread availability of medical birth control. The one-child policy, estimated to have prevented between 250 million and 500 million births, had the effect of pushing China’s birthrate away from that of a developing closer to one much more characteristic of a developed country. But as the chart below shows, as based on UN data, China’s birthrate had already slowed long before the one-child policy took hold.

(Nielsen)

Had China done nothing, fertility rates would have naturally continued to decline — and all without expending the costly efforts to restrict freedom in such an intimate and fundamental way.

For all the costs of enforcing the most restrictive family planning in world history, China doesn’t have much to show as a result.

China’s median age (today) is 36.7 — that’s akin to Iceland and just slightly younger than the United States (37.6), Australia (38.3) and Russia (38.9). The United Nations estimates that by 2025, China’s median age will be essentially the same as the US median age and, thereafter, China’s median age will be ever older.

As its neighbors South Korea (40.2) and Japan (46.1) have aged, however, economic growth has slowed. That might be fine for South Korea and Japan, because they now both enjoy income levels roughly equivalent to developed countries. China, though it’s well on its way to becoming the world’s largest economy, has only just reached middle-income status. So the one-child policy might have put China on a slightly less fertile trajectory — but only slightly.

With economic uncertainty looming, it seems likely that the era of residual double-digit GDP growth in China is coming to an end. So while China has ‘caught up’ on aging, it hasn’t quite caught up on income levels and per-capita GDP. Even when China transcends its current economic gloom (and it will), it will be more difficult for it to play catch-up with an aging population and fewer working-age people in the labor market. Moreover, the low-hanging fruit of the past three decades — building the infrastructure (hospitals, bridges, schools, entire towns and cities) for a rapidly modernizing country — will be increasingly out of reach for economic planners.

Exacerbating China’s demographic woes is one of the world’s most lopsided sex ratios — only 100 women for every 112 men. There are a lot of reasons for that, including a sex ratio that tilts naturally at around 1.01 in favor of males. But given traditional cultural preferences for males, more Chinese families have opted to ensure that the single child permitted to them is male and not female. In a country of 1.38 billion people, that means that tens of millions of Chinese men have had and, for the foreseeable future will have, only negligible chances for marriage or starting their own families. At a time when economic misery is rising in China, that’s not particularly good news for ruling Party officials who could struggle to contain political and social anger in the event of a prolonged economic slump.