After five rounds of voting that ended on Thursday, the results of Bihar’s state elections were revealed last Sunday, handing a surprisingly strong victory to chief minister Nitish Kumar — and a correspondingly disappointing defeat to prime minister Narendra Modi that’s caused ripples nationally and ripped the aegis of invincibility from Modi’s political cloak.![]()

With 104 million people, Bihar has a population twice that of Myanmar/Burma, whose elections have been received with far more international coverage. Though it’s not even India’s most populous state (it ranks third), Bihar is home to more people than all but 11 countries in the world. It’s here, in one of India’s poorest states, that a regional election drew into conflict three of India’s most colorful and powerful politicians and where two distinct (and imperfect) visions of India’s development have clashed, with a result that will have national implications for India’s future.

To understand the real significance of the Bihari election, it’s worth taking a step back to understand the decade-long posturing between Modi and Kumar. Bear with me.

A tale of two visions of ‘vikaas’

The first of those two visions belongs to Modi, whose Bharatiya Janata Party (the BJP, भारतीय जनता पार्टी) so overwhelmingly won national elections in May 2014. That was just as true in Bihar as it was elsewhere in India, where the BJP took 22 of the state’s 42 seats in the Lok Sabha (लोक सभा), the lower house of the Indian parliament. In part, Modi was selling a vision of development and economic progress based on the ‘Gujarati model’ that he laid claim to after 13 years as chief minister of the state of Gujarat. The Modi approach involved a top-heavy approach to government and economic boosterism that found Modi jetting to China, Japan and the United Arab Emirates to cajole foreign development to his state. Though Gujarat’s economy has always been among India’s stronger performers, there’s no doubt that Modi’s zero-tolerance approach to corruption and attention to strong infrastructure, including some of the best roads and power generation in India, has been successful. Despite the Hindu-Muslim riots that left over 1,000 Muslims dead shortly after Modi took office in 2001, Modi’s 2014 campaign slogan of ‘toilets, not temples’ rang true — he was a man more interested in bringing good roads and clean water to his country than giving voice to Hindu nationalism, or at least that was the promise of his campaign.

But there was always another model, and that’s Kumar’s Bihari model.

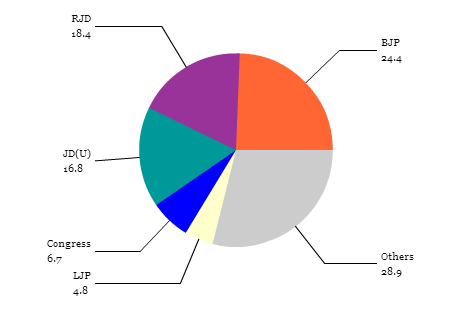

Ultimately, it was this model that won the day in this autumn’s elections — a five-phase spectacle over the course of nearly a month, between October 12 and November 5. When the results were announced, Kumar’s Mahagathbandhan (‘Grand Alliance’), a coalition between his own Janata Dal (United) (JD(U), जनता दल (यूनाइटेड)) and the Rashtriya Janata Dal (RJD, राष्ट्रीय जनता दल), the party founded in 1997 by former chief minister Lalu Prasad Yadav, won a clear mandate, far larger than anyone had expected in what was thought to have been an incredibly tight race.

The Kumar-led alliance won 41.9% of the vote and 178 seats in the state’s 243-member Legislative Assembly, while Modi’s alliance won just 34.1% of the vote and 58 seats, far more lopsided than anyone had predicted.

Kumar’s story — and his relationship with the BJP — is complex.

Except for a short period between May 2014 and February 2015, when he briefly stepped aside after his party’s loss in India’s national election, Kumar has served as Bihar’s chief minister since 2005, and for most of that time, he was an ally of the BJP in the National Democratic Alliance (NDA).

Kumar took over a state known as something of an economic basketcase. Even today, Bihar has a far higher poverty rate than much of the rest of the country. When you think of overpopulated and underdeveloped India, you are probably thinking of Bihar or somewhere very much like it. In contrast to Bangalore or Mumbai or even Modi’s Gujarat, Bihar’s hopes never lied in the kind of sexy development that comes from foreign investment. But over the course of Kumar’s tenure as chief minister, he has managed some of the highest GDP growth rates in the country (including an average GDP growth rate of 10.6% between 2005 and 2014) and an 8% reduction in poverty. Like Modi in Gujarat, Kumar focused on infrastructure, including better roads. But he also turned to greater social welfare spending and his record on poverty reduction is far stronger than Modi’s Gujarati record.

But perhaps Kumar’s greatest governance success came from reversing the sense of lawlessness that characterized Bihar under the leadership of his predecessor (and now coalition partner) Lalu Prasad Yadav.

Becoming chief minister for the first time in 1990, Yadav reigned over what became known nationally as a ‘jungle raj,’ a state of wild corruption, economic malaise and violent criminals riding roughshod. In 1997, when he was implicated (and eventually convicted) for accepting kickbacks in an animal husbandry scheme known as the ‘fodder scam,’ he stepped down in favor of his wife, Rabri Devi, who intermittently ruled as chief minister until 2005. At the same time, Yadav founded a new breakaway party form the Janata Dal, the RJD.

The two remained enemies for the better part of a decade and a half. As the RJD became a byword for petty corruption (even today, 49 of the 80 incoming state legislators have pending criminal cases), Kumar promised a new approach that transcended religion and caste, nominally an ally of the BJP, while Bihar’s green shoots emerged in the mid-2000s onward.

In 2013, as it became apparent that the BJP and the NDA favored Modi to lead the alliance into the 2014 elections as a prime ministerial candidate, Kumar withdrew from the alliance. He did so mostly because of Modi’s role in the controversial 2002 communal violence and riots in Gujarat. Just as the BJP was about to win the most massive victory in Indian history, Kumar walked away from the alliance, in no small part over secularism. One suspects that it also had to do with Kumar’s disappointment in not leading the alliance himself. But for years, Kumar has refused to let Modi’s campaign in Bihar, and his disapproval of Modi’s record had been on record for years.

How the ‘Grand Alliance’ stole Bihar back from Modi

The 2015 Bihar elections were supposed to be one of the great triumphs on Modi’s path to consolidating the BJP’s power, and the prime minister campaigned throughout the state early and often at the advice of his chief strategist, Amit Shah.

But something went awry.

In contrast to the ‘toilets, not temples’ mantra of his 2014 campaign, the BJP got bogged down in an attempt to use communal issues, like eating beef, to fire up its Hindutva base in India, a step that seems to have backfired. Despite Modi’s popularity, the BJP might have benefited from grooming a local charismatic figure that could have led the party’s efforts in Bihar. Through the campaign, it was never quite clear who would become chief minister had the BJP won the election, unlike the ‘grand alliance,’ which made clear that Kumar would carry on as chief minister if elected. Unlike Modi, just 18 months into his tenure as India’s prime minister, Kumar has a decade of proven results as chief minister. It’s not crazy to think that Bihar’s voters are sophisticated enough to support Modi nationally and Kumar locally.

Yet one of the reasons that the BJP did so well in the 2014 national elections in Bihar was that the JDU and the RJD were divided. Though the Nitish-Lalu alliance has generated its fair share of wariness, given the 15-year rivalry between the two figures, the coalition between the JDU and the RJD made it much easier to unite Muslim supporters (in a state where over 15% of the population is Muslim) and the disadvantaged Yadav caste.

Joining forces wasn’t easy for Kumar, whose good-governance agenda has little in common with the RJD’s pocket-lining. But the Indian National Congress (Congress, भारतीय राष्ट्रीय कांग्रेस), previously the governing party of India, engineered the coalition between the two parties and joined up as the third, by far weakest, partner of the alliance in Bihar. Rahul Gandhi may be a ghost when it comes to contemporary Indian politics, and aside from its overrated role in bringing Kumar back together with the corruption-tainted Lalu, has been entirely absent from the Bihar campaign (as in Delhi, where Arvind Kejriwal delivered a whopping defeat to Modi earlier this year).

Lalu, as a politician, is one of India’s greatest showmen. He toured every corner of Bihar state, and he used the campaign to attack the hardliners who have dominated headlines in India for their Hindu nationalism since Modi took office. It worked, and his party (the RJD) won more seats than Kumar’s JD(U). He’ll expect something in return for that victory, and it might be more than just a space in Kumar’s next cabinet for his two ambitious sons.

The consequences for Modi’s government and the road ahead

There’s no doubt that the Bihar electoral rout is the worst political crisis since Modi took power nearly 18 months ago. Modi’s enemies in his party, including the old guard that he sidelined two years ago, have now called into question the highly centralized approach that Modi has taken to India’s government.

But as much as the Bihar elections represent a loss for the BJP and for Modi personally, it’s not fatal. Though it’s true that Modi’s government has gotten off to a slow start as far as reform goes, he has more than enough time to right the course. The next Indian general election will not take place until 2019. In the meantime, he should double down on reform. Despite the fact that many BJP parliamentarians are protectionsist, he should push full speed ahead with a reform of the national goods and services tax that will harmonize rates and rules across state lines. As far as regulation goes, this isn’t a Thatcherite rupture, it’s low-hanging fruit. Land reform and steps to reduce graft, make government more transparent and businesses more efficient would be welcome. As far as development goes, Modi would do well to copy Bihar’s program of providing free bicycles to girls and incentives for primary and secondary education.

He might even work with Kumar in the weeks and months ahead to merge the best of both models, two sides of the same pro-development coin. Nothing would get Modi’s government back on the path of ‘toilets, not temples.’ That’s especially true with a tough set of state elections coming in 2016 and 2017. No one expects Modi and the BJP to sweep Tamil Nadu or West Bengal, where local parties rule supreme. But the 2016 election in Assam is winnable, and the fight for Uttar Pradesh, India’s most populous (and still quite impoverished) state in 2017 will be fierce. A loss there will not doom Modi’s chances in 2019, but an embarrassing loss just might.