Last Friday, after a campaign of less than two weeks, the People’s Action Party (PAP), which has governed Singapore without interruption since 1959, won a fresh mandate, as thoroughly expected.![]()

But for a party that’s ruled Singapore since before its independence from Malaysia, the PAP returned to power with an unexpectedly larger share of the vote than it won in the last elections in 2011, an impressive feat at a time when the country’s young and elderly alike are feeling the economic crunch.

The PAP’s victory wasn’t from lack of effort by the opposition, which fielded candidates in every constituency. Nor was it from complete satisfaction with the PAP. Voters have increasingly aired frustrations about the government’s ability to deal with escalating prices, inadequate retirement funds and the puzzle of how to sustain the breakneck economic growth that characterized Singapore for the past half-century.

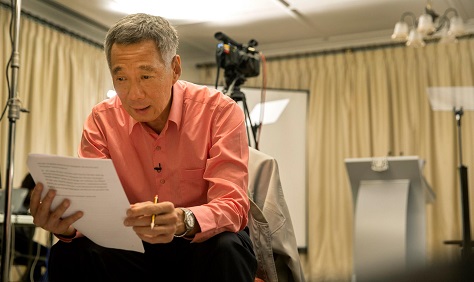

Nevertheless, the PAP improved its share of the vote by nearly 10% (to 69.9% from 60.1% in 2011). While 60% support would amount to landslide territory in a more competitive democracy, it was a serious setback for the PAP and its leader Lee Hsien Loong, prime minister since 2004 and the son of Lee Kuan Yew, the country’s first leader who presided over Singapore’s emergence as a wealthy, developed country.

So what happened?

It’s impossible to distill a national election to a simple narrative, even in a place as small as Singapore (a city-state of just 277 square miles with a population of around 5.5 million). But there are at least three trends that explain why the PAP emerged so strongly from the 2015 snap elections.

1. The government’s sharp timing

It’s not hard to understand why the PAP would want to hold elections at the end of 2015 instead of waiting until autumn 2016. From a nostalgic point of view, the vote followed both the death of Lee Kuan Yew in March and the country’s 50th anniversary in August. To proceed straight into elections in September made sense as a natural valdedictory progression from the National Day celebrations.

But the government has been tinkering with policy all year long — tweaking the ability of everyday citizens to pull out money from their mandated retirement accounts and a dedicated push for more affordable housing. While economic growth has slowed for a decade, and while inequality and even poverty seem to be increasing in Singapore, it’s a smart bet that the current economic situation is far better than it might be in 12 months’ time, if the Chinese economy contracts, a shock that could have brutal regional and even global effects.

It is true that rolling the dice with early elections meant riding a feel-good wave among longtime voters who look back on the past half-century with fondness. But more importantly, it also meant getting ahead of what could be a very nasty economic downturn.

2. The unknown is still scarier than the known

The PAP’s triumph, of course, does not mean that Singaporeans are thrilled with their government Far from it. But the PAP is responsible, for better or worse, for the record of the last half-century, and there’s no doubt that living standards, over the course of PAP rule, are much improved. So while there are real grievances among the electorate about rising housing prices, the exorbitant cost of living and the sense that the country’s mandatory retirement scheme, the Central Provident Fund, is too restrictive and offers a tepid return that often fails to keep up with inflation, let alone the returns of Singapore’s sovereign wealth funds, there’s still a lot of anxiety to throw the PAP out of power.

Singapore has always been a tough country for Western critics because it shares some of the qualities that Westerners associate with ‘good government’ (low corruption, a highly capable and well-educated civil service and thoughtful and creative approaches to policy) with the qualities some of the world’s most autocratic regimes (limits on individual expression that sometimes border on the ludicrous, a highly restricted press and a challenging environment for political opposition).

Moreover, considering its neighborhood, there are few local precedents for strong, competitive democratic rule — Indonesia is a young emerging democracy, and Malaysia is a democracy in name only, divided strictly on ethnic lines while its most charismatic opposition leader sits in jail on exaggerated political charges for ‘sodomy.’

A vote against the PAP isn’t like a vote to switch from Republican to Democrat — for voters, it represents a far wilder shot in the dark for opposition parties with no experience governing Singapore. The country may have its problems, but given the issues (and incomes) of its neighbors, including imperfect democracies like Indonesia and Malaysia, voters so far seem unwilling to take a chance on a new leadership class. It’s a fear that the PAP — like any survivor in a long-term, one-party state — is skilled at exploiting.

To that end, Lee Hsien Loong pitched the contest as the testing ground for a new generation of PAP leaders. Though his father only died six months ago, the 63-year-old Lee has hinted more than once that he may well step down before the next elections. Furthermore, he made no secret of the fact that he believed that this election was important for grooming Singapore’s third generation of policymakers. In so doing, Lee shrewdly cloaked the PAP’s campaign in the shroud of change as much as continuity, giving voters the excuse to vote PAP as a running start at reform from within.

3. A divided and weak opposition

Quick — try to name the leader of the chief opposition party. For that matter, try to name the party itself. (It’s Low Thia Khiang, and he leads the Workers’ Party).

But the problem in 2015 wasn’t the Workers’ Party, actually, which held onto the sole multi-member constituency, Aljunied, that it first won in the last election. Though it will fall from nine seats to eight in Singapore’s parliament (the PAP will hold 83), the Workers’ Party still won 12.5% of the vote, just a fraction less than it won in 2011 (and, in absolute terms, 20,000 votes more than it won last time).

The real collapse came among the opposition’s smaller parties, including a dramatic drop in support for the National Solidarity Party, as well as more narrow losses for the Singapore Democratic Party, the Reform Party and the Singapore People’s Party.

In contrast to Malaysia’s charismatic (and now imprisoned) opposition leader Anwar Ibrahim, the quiet confidence of longtime Burmese reformer Aung San Suu Kyi, or the vibrant populism of the Shinwatra siblings in Thai politics for the last 13 years, Singapore’s opposition lacks the kind of forceful figure that could unite leftists, reformers and activists behind a single-minded campaign to oust the PAP.

If you’ve heard of anyone challenging Singapore’s ruling elite these days, it might well be Roy Ngerng, a blogger whose criticisms of PAP rule have earned him a defamation lawsuit from Lee Hsien Loong and a looming sentence that might easily bankrupt him. A candidate for the Reform Party in the 2015 elections, Ngerng barely won more than 20% of the vote. But he represents a new generation of young Singaporeans, and the harsh criticisms that he and a group of like-minded (and, given the government’s use of Singapore’s strong libel laws, courageous) writers have leveled at the PAP, demanding greater accountability and transparency, have sounded a resonant chord throughout Singapore.

Openly gay in a society that’s still very conservative, Ngerng has also worked for more understanding of those who suffer from HIV. At 34 and under a cloud of legal uncertainty, the 2015 election wasn’t perhaps the opportune moment for Ngerng’s political debut. But the splash he’s made, both in Singapore and abroad (and that the government amplified by pursuing him so relentlessly for free expression), means that he could play an important role in the future of Singapore’s governance.